In 2009, Joshua Fields Millburn and Ryan Nicodemus were childhood friends living in Ohio and working hard toward achieving the American dream. They had corporate jobs making six figures, suburban houses, and plenty of stuff. But it wasn’t all perfect: They also struggled with debt, addiction, and exhaustion. In the fall of that year, Millburn’s mother died, and his marriage fell apart. He started to realize that he was unhappy and unhealthy. “I wasn’t living the Dream,” he later wrote. “I was living a lie.”

Scrolling through Twitter one day, he discovered a video by someone named Colin Wright, who owned very few possessions, traveled full time, and called himself a minimalist. Millburn was attracted to the idea and began working to simplify his life. He recruited Nicodemus, who had been feeling similar discontent, to the cause. At the end of 2010, dubbing themselves “The Minimalists,” the pair launched a blog about their journey. The next year, they left their jobs and self-published their first book. Blogging and speaking events brought media appearances, and their holistic message of eschewing materialism in order to find freedom garnered new followers. Whereas in the early days they would have been lucky to get 50 people at an event, by 2017 they could draw 500.

Millburn and Nicodemus call themselves the minimalists, but they aren’t the definitive article; they’re part of a larger trend that has swept the United States over the past decade. Before the duo’s conversion, people like Wright and Joshua Becker, a former pastor, were already chronicling online their adventures in living with less. Japan’s foremost decluttering expert, Marie Kondo, landed in the United States in 2014 with the English-language version of her book The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying Up, which has sold millions of copies and spent more than a year on the New York Times bestseller list. KonMari (as her method is called) mania, which instructs followers to keep only those items that “spark joy,” reached new heights in 2019 with the release of a Netflix reality-TV show, Tidying Up With Marie Kondo, that has overloaded thrift stores with donations.

Downsizing today isn’t just a process; it’s a lifestyle that comes with its own aesthetic—minimalism as visual brand. It’s the careful framing of the objects that represent you and therefore matter: white walls and lone lamps and burnished wood furniture and a carefully placed sprig of green. It’s the design of your iPhone as well as many of the photos you scroll through (on apps like Instagram and Pinterest) while using it. Minimalism is tiny houses, floor-to-ceiling glass condos, and the homogenized industrial-chic decor of coffee shops and work spaces that allows white-collar workers to travel between cities and countries without feeling as if they’ve gone anywhere at all. According to the website Apartment Therapy, minimalism is so vast that there are at least six distinct strands of it, from experiential to mindful, and more.

How did the United States, a nation whose credo is consumption, where the average household owns 300,000 items, and where bigger is assumed to be better, come to embrace an anti-consumerist, austerely styled trend—and one with the same name as a 1960s art movement? Or, as journalist Kyle Chayka puts it in his new book, The Longing for Less: “How did an unlikely avant-garde phenomenon become the generic luxury style of the 2010s, both an aesthetic commodity and an ascetic philosophy at the same time?” The book doesn’t completely answer that question, nor does it attempt to present a definitive history. Instead, Chayka wants “to uncover a minimalism of ideas,” tracing the thought that less could be more through movements and moments in art and architecture, sound and music, and philosophy. The minimalism he finds is not about getting organized in order to regain control (or the illusion thereof); it’s about exploring the artistic and existential possibilities of reduction.

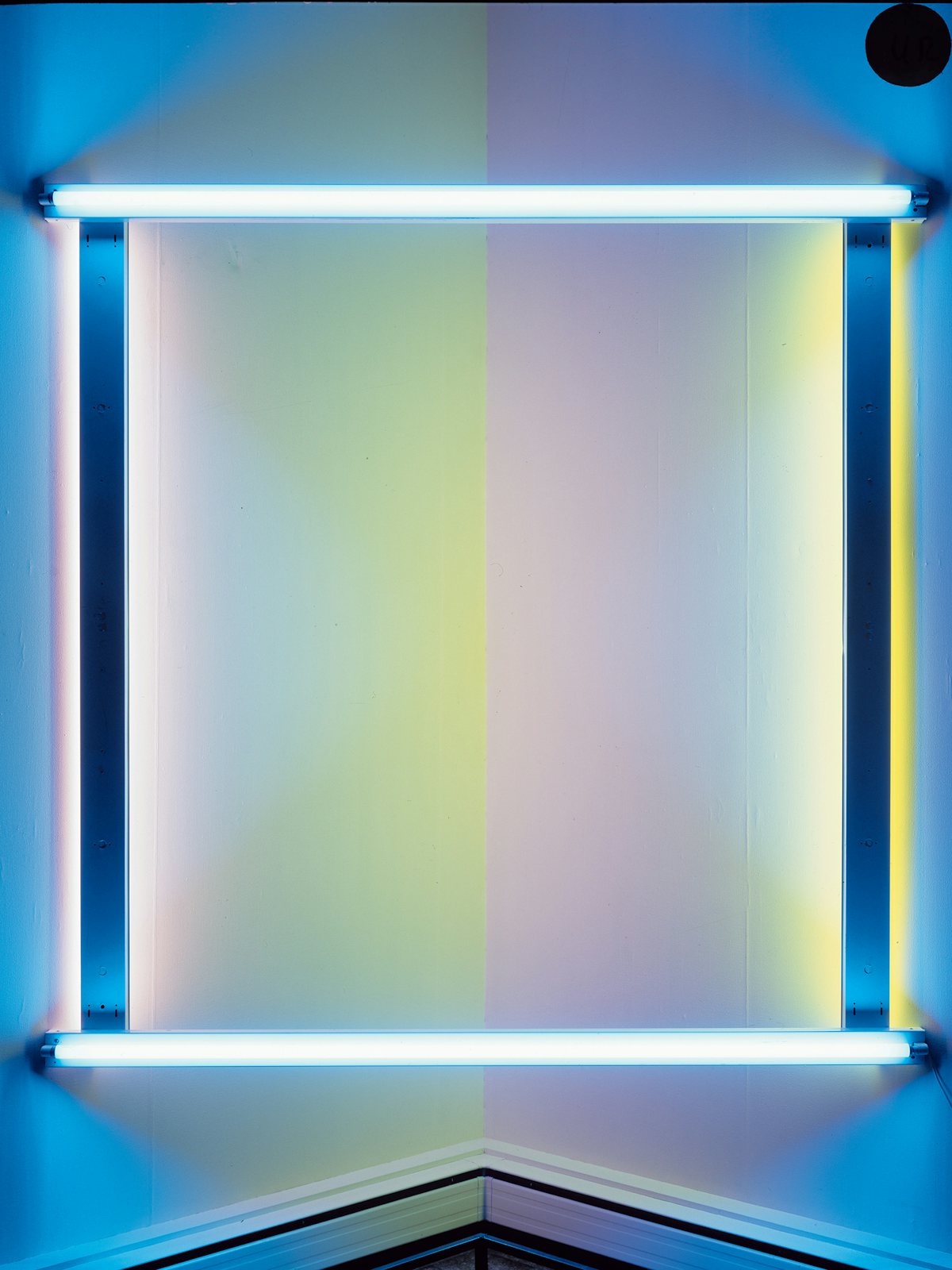

“Minimalism” is now an accepted historical term and a mainstay in any museum telling the story of modern art, but the artists to whom the word was applied never liked it. In New York City in the 1960s, Donald Judd, Dan Flavin, Robert Morris, and others began showing works that didn’t look like what was commonly accepted as art. In contrast to the gestural brushstrokes of Abstract Expressionism or the meditative marks of Color Field painting—two dominant styles of the preceding decade—these artists presented simple, solitary, often geometric objects that seemed to contain no symbolism or reference points. Whether Flavin’s fluorescent light bulbs or Morris’s painted plywood slabs and shapes, these works did not seem to represent anything beyond themselves.

In 1965, Judd wrote an essay championing this quality. “It isn’t necessary for a work to have a lot of things to look at, to compare, to analyze one by one, to contemplate,” he proposed. “The thing as a whole, its quality as a whole, is what is interesting.” He noted the prevalence of unusual materials, especially industrial ones reminiscent of modernist architecture, like the metals he used to make the freestanding boxes and wall-mounted, stacked rectangles for which he would be known. Judd identified these “specific objects” as neither painting nor sculpture and thus free from the associations and limitations of those mediums. In the new style, “a work can be as powerful as it can be thought to be,” he wrote.

At first, onlookers didn’t know what to do with these objects. Critics complained and called them different names: “ABC Art,” “Literal Art,” even “Boring Art.” The term “Minimalism” ultimately arose from a 1965 essay by the British philosopher Richard Wollheim titled “Minimal Art,” in which he considered the value of different types of work with “minimal art content.” Somewhat ironically, given that the label clung to them for the rest of their careers, Wollheim wasn’t actually writing about Judd and his contemporaries.

It’s a testament to the effectiveness of Minimalist art that it can still draw and confound viewers today. The Museum of Modern Art is betting on this with a large Judd retrospective this spring. The promotional image for the exhibition shows an untitled work from 1991 that’s made of dozens of discrete enameled aluminum rectangles stacked and bolted together to create a single large unit—almost like an abstracted dresser or bookcase. What to make of such an object sitting on the floor of a white-walled gallery? What does it mean? The goal is for viewers to experience and interact with the work as it looks and simply is, allowing it to generate feelings and prioritizing sensation over interpretation. Form becomes content. Minimalism “tries to make us understand that the sense of artistic beauty humanity has built up over millennia … is also an artificial creation,” Chayka writes. It requires “a new definition of beauty, one that centers on the fundamental miracle of our moment-to-moment encounter with reality, our sense of being itself.” Although it often looks sleek and shiny, this work doesn’t offer the tidy frictionlessness of a pared-down home. Often difficult and unsettling, it is intended as a confrontation.

In their embrace of industrial materials, the Minimalists were drawing on modernist architecture, although with a very different goal in mind. Whereas the artists were attempting to empty art of its preconceived notions and its need for inherent meaning, the architects were striving for a utopian promise: the idea that mass production and standardization could help bring about a better society, or what Chayka calls “a vision of a safer and cleaner world, with cosmopolitan equality for all who inhabited its architecture.” Beginning in the early twentieth century, architects across Europe started moving away from the predominant, often ornate styles in the field toward more modest, streamlined, glass-and-steel structures shaped by their function. “Making things simpler and blanker was cast as a form of progress,” Chayka writes. The leaders in this arena were Le Corbusier, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, and Walter Gropius, who founded the Bauhaus in Germany in 1919. A school of art, design, and architecture, the Bauhaus preached a philosophy of total aesthetic synthesis, the ultimate modernist ideal.

Today, this trend in architecture is known as “International Style”—a term coined by American curator and architect Philip Johnson. Johnson was friends with Alfred Barr Jr., the founding director of MoMA, and joined its architecture department soon after the institution opened in 1929. A few years later, he curated an exhibition there that showcased the new modernist style, and in 1947 he organized a retrospective of van der Rohe’s work. The latter included a model of an in-progress house that consisted of a thin glass rectangle sandwiched between two white slabs of painted concrete. Johnson was so inspired by the unconventional structure that he ripped it off and built his own.

Rising in the woods of Connecticut in 1949 (before the completion of van der Rohe’s similar project), the Glass House was the original condo with floor-to-ceiling windows. It’s arguably as minimal as a building can be, with exterior walls made entirely of glass set into an unadorned steel frame. Inside, furniture and objects are sparse, and there are no walls, only “zones,” as Chayka calls them, designated for different functions. At first, it didn’t even have curtains. The small house is a beacon of clarity and transparency—a sort of platonic ideal for existing in harmony with your surroundings. Johnson (along with his partner) lived there until his death in 2005, hosting artists and performances and breathing in the beautiful, nature-filled views surrounding him.

For the Minimalists with their confrontational art and for Johnson with the Glass House, a stripped-down aesthetic was partly about forging a more authentic encounter between the self and the world. But beneath the smooth surfaces, there were problems. Because Johnson prioritized the look of the place over everything else, the building had structural issues, including a leaky roof, and a lack of air vents that led to condensation-covered walls. The first night that he slept there, he turned on the lights only to find that they bounced off the walls and returned his own reflection, rather than showing him the landscape he wanted to see (he solved this by installing outdoor lights). The Glass House appeared open and uncomplicated but in fact was elaborately austere. The need to preserve its visual cleanliness limited the kind of life that could be lived inside it.

What’s more, Johnson took widely available materials and used them to construct a home that was well out of reach for most people. “It’s a house built for and by a single person, demonstrating a kind of megalomaniacal possessiveness,” Chayka writes. Rather than something utopian, the architect made an object of desire, something cool and elitist. The Minimalist artists, working several decades later, unintentionally found themselves in the same situation.

Whereas Judd’s shiny boxes and Frank Stella’s striped, monochrome Black Paintings began as repudiations of traditional definitions of art, they quickly became the next hot thing in the field. Collectors wanted to buy the work, and galleries evolved to better display it, embracing “architectural blankness,” in Chayka’s words, by becoming white cubes. At the same time, Minimalism spilled over into interior design, in part thanks to the five-story former SoHo factory that Judd had bought and turned into his studio and home. At 101 Spring Street, unadorned yet elegant furniture cohabitated with austere works by the artist and his friends, all accentuated by large rows of windows. “The view across the bedroom, where art takes up more space than the bed, inspired a thousand Dwell photo shoots,” Chayka writes.

Half a century later, we’ve kept the aesthetics but jettisoned the ideas that drove them. Minimalism has been reduced to an aspirational style—a measure of taste and an opportunity to announce your sophistication. By buying and having less, you can demonstrate that you and the things you do own are worth more. If Minimalist art was a void, then theoretically anything could rush in to fill it. The movement’s fundamental “emptiness helped it slide along this path to commodification,” Chayka writes. “It could be whatever you wanted it to be,” and it was easily replicable.

The Minimalists, who were mostly white men, believed that by removing any trace of their own hands, they could create and operate within a realm of nonpersonal neutrality—a fantasy that often ended up as a whitewashing of their influences. Building something on a foundation of nothingness is itself an old idea and one prominent in Zen Buddhism, which Judd studied. And while Minimalist works were devoid of obvious content, they still had substance: the materials they were made from and the forms they took. Looking critically at many of them reveals conservative values hiding in plain sight, as Anna Chave posited in her 1990 essay “Minimalism and the Rhetoric of Power.” For example, she sees in Richard Serra’s creation of hulking metal forms “the rituals of the industrial magnate who merely lifts the telephone to command laborers to shape tons of steel according to his specifications”; many of Flavin’s light bulbs are plainly phalluses. Chave identifies the two most common qualities of Minimalist art as “unfeelingness and a will to control or dominate.”

In fact, the alleged blankness of Minimalism can serve as a facade that conceals a disturbing reality. An incident that Chayka doesn’t discuss in his book demonstrates this in an extreme way. In 1985, the Cuban American artist Ana Mendieta fell to her death from the thirty-fourth-floor apartment in Greenwich Village that she shared with her husband, the Minimalist sculptor Carl Andre, who’s best known for arranging bricks and metal plates on the ground. Shortly beforehand, the doorman heard a woman yell “No!” several times. Andre, who had scratches on his nose and forearm, told the 911 operator that the two had had a fight and Mendieta “went out the window.” He was tried for murder and acquitted.

The event split the New York art scene immediately, with some people rallying to protect Andre and others blaming him for her death. The divisions intensified after his acquittal and have remained to this day, with Andre’s defenders claiming that he was ostracized after Mendieta’s death, and his detractors arguing that he has been sheltered from facing any consequences by the success of his monumentally neutral art. “Andre’s work survives Mendieta’s death and this kind of judgment partly because the work itself doesn’t speak to any emotional life,” wrote Maya Gurantz in a 2017 essay for the Los Angeles Review of Books. “Death and blood and womanizing and his open alcoholism (which he conveniently blames for his memory loss) doesn’t stick to his orderly metal plate and brick arrangements.” A retrospective of Andre’s work that opened in 2014 was disrupted by protesters at several of the institutions where it went on view; they objected to the erasure of Mendieta and her death from the story of Andre’s life and art.

For Chayka, true minimalism offers a reduction so radical that it spurs a renewed engagement with the world. That may be true, but its filtering out or ignoring of the messy realities of society—by, say, making blank metal objects in the midst of the upheaval of the 1960s and ’70s—is also a form of retreat, an escape enabled by a position of privilege. It seems possible that even Judd realized this, to a degree. In a contribution to Artforum in 1970, he wrote of his early “attitude of opposition and isolation,” which grew out of his “incapacity to deal with” global events of the 1950s. “Unlike now, very few people were opposed to anything, none my age that I knew,” he wrote. “So my work didn’t have anything to do with the society, the institutions and grand theories.”

In its own way, too, contemporary minimalism has little to do with “the society, the institutions and grand theories.” Despite its anti-consumerist bent, the trend focuses more on personal improvement than on any kind of structural critique. Practitioners tell you how you can be happier with fewer possessions but rarely ask why it is that Americans own so much stuff. Millburn and Nicodemus’s 2016 film Minimalism: A Documentary About the Important Things combines footage of people storming big-box stores for sales with social scientists talking about how advertising drives us to consume, but the word “capitalism” is never uttered during its 78 minutes. I caught one mention of “inequality.” Instead of digging into systemic problems like poverty or exploring ideas of wealth redistribution, the film frames having less as an individual, moral choice with no political strings or implications. In his book, Chayka sums up this approach as: “Your bedroom might be cleaner, but the world stays bad.”

In fact, the most interesting scene in the movie comes when an audience member at one of Millburn and Nicodemus’s events calls them out on this. “You’re dedicated, you’re creative, you’re innovative,” says a man named Clyde Dinkins during the Q&A. “You have a sincere desire for mankind—the very people who the wolves of Wall Street fear. And to me, you’re removing yourself from the war.”

It’s a thrilling moment and the only one of genuine tension, when cracks appear in the smooth white surface of the documentary’s all-encompassing minimalist-savior narrative. Millburn and Nicodemus listen to Dinkins and respond as best they can. They give him hugs afterward, as is their way. But then the story moves on, never to return to this point of contention. The pair quickly seem to forget Dinkins’s words, which for me are only thing worth keeping in the movie, the little bit of it that sparks joy: “The ultimate minimalist is a hermit, a recluse, or a monk,” he says. “And to me, that’s not gonna change the world.”