It’s long been an article of faith among Democrats that they have nothing to learn from Republicans. Democrats tend instead to believe that the GOP is the party of evil that achieved power through underhanded methods such as suppressing the votes of minorities. While this is true to some extent, Republicans have also used and mastered methods that are simply Politics 101. Democrats could copy any number of these techniques without reservation—and with no small benefit. Here are a couple of cases in point.

For many years, Republicans embraced the conventional wisdom that national elections were won in the middle of the political spectrum. Presidential candidates ran to the right during primaries and pivoted left—toward the middle—after the convention. Richard Nixon was probably the master practitioner of this strategy. But even as recently as 2000, George W. Bush ran in the general election on “compassionate conservatism” in order to reach out to moderates and centrists.

In 2004, however, Bush’s principal political adviser, Karl Rove, convinced him to adopt a new strategy—instead of reaching out to those in the middle, it was better to ramp up turnout among those who were already Republicans. Polarization, not compromise, was the key to victory.

According to exit polls, 35 percent of voters identified as Republicans in 2000 and 39 percent as Democrats, with 27 percent independent. Bush captured 91 percent of the votes of Republicans, while Al Gore got only 86 percent of the votes of Democrats. They roughly split the independent vote.

In 2004, however, Bush was able to increase Republican turnout to 38 percent of the electorate and raised his share of the Republican vote to 93 percent, while John Kerry captured 90 percent of the votes of Democrats, who also represented 38 percent of voters. The combination of these effects raised Bush’s share of the popular vote to 50.7 percent in 2004 from 47.9 percent four years earlier.

This explains why Donald Trump governs as if he represents only Republican voters; he basically does. While it remains to be seen whether this is a sound general election strategy, there is no question that Republicans strongly approve. Trump’s approval among them is consistently more than 90 percent, according to Gallup. The Republican share of the electorate has not fallen and is about the same as it was on election day 2016.

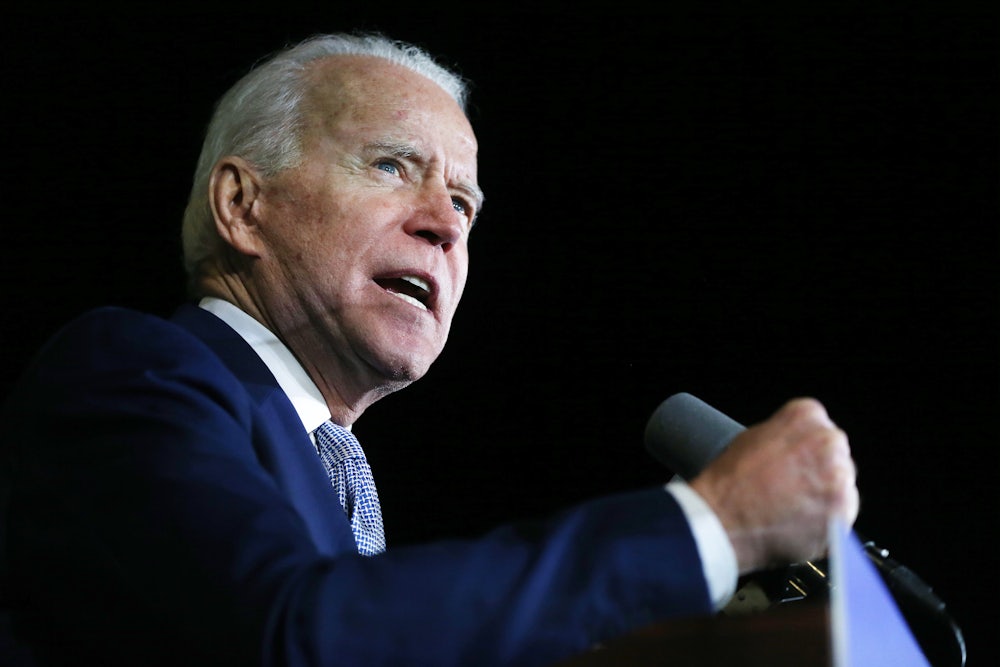

Clearly, Trump believes that turnout will be the key to his reelection. Toward that end, he supplies Republicans with a steady diet of red meat that often involves lies, conspiracy theories, and mean-spirited attacks on Democrats, the media, and other perceived enemies. Meanwhile, Joe Biden ran as a moderate in the primaries and must now pivot left to shore up the Democratic base.

Since the election will be, more than anything else, a referendum on Trump, Biden may not need much more than a pulse to win this year, especially given the prostrate economy and Trump’s incompetent handling of the pandemic. However, any hope Democrats have of reversing Trump’s policies will depend vitally on gaining control of the Senate. That is where turnout and Democratic enthusiasm will really matter.

There is still time for Biden to fine-tune his policies and choose a running mate who can play the traditional role of attack dog, charged with arousing the party faithful. But building a stable governing majority will require a higher turnout among Democrats in both presidential and congressional elections. That will demand more attention to traditional Democratic voters.

A key reason why Republicans became the governing party is that they courted and cultivated Democratic voters alienated from their party for various reasons. Democrats call this the Southern Strategy because it frequently involved playing the race card, using code phrases like “law and order” to pull racists over from the party they had belonged to since the Civil War.

But it is simplistic to think that veiled racism was all it took for Republicans to achieve dominance. A lot of the GOP’s crossover appeal had to do with retail politics—recruiting good candidates and providing them with the resources to run competitive races. Historically, many Southern Democrats in Congress ran unopposed in the general election; the only election that really mattered was the primary.

To his credit, Newt Gingrich realized how vulnerable many of these Southern Democrats were—in effect, the GOP was giving a pass to Democrats holding precisely those seats that were most likely to flip under more concerted pressure from the right. Many Democratic incumbents were complacent from years of running unopposed and had done little to raise money or maintain a political organization in their states and districts. After Gingrich was elected to Congress from Georgia in 1978, he made it his mission to go after these legacy officeholders and make them work hard for reelection. And unlike smokers in the old TV commercial, they often chose to switch (parties) rather than fight. Their seats fell into the hands of the GOP like ripe fruit.

Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, there was a steady stream of Democrats who became Republicans, following in the footsteps of Senator Strom Thurmond of South Carolina, who defected in 1964. Republicans were generous to those crossing the aisle. Senators Richard Shelby of Alabama and Ben Nighthorse Campbell of Colorado were allowed to keep their seniority after going over to the GOP, rendering the decision all but cost-free to their careers. By contrast, when Senator Wayne Morse of Oregon switched from the GOP to the Democratic Party in 1955, he lost all his seniority and went to the bottom of the seniority list, losing valuable committee assignments in the process.

In a similar vein, conservatives in the 1950s and 1960s eagerly embraced former Communists, such as Whittaker Chambers. Brooklyn College political scientist Corey Robin says that these apostates from the left were extremely valuable because they understood the left’s vulnerabilities much better than those on the right did. When I went to work on Capitol Hill as a Republican in the 1970s, much of the best political and policy advice I could find came from a group of former leftists affiliated with a small journal called The Public Interest, edited by one-time Trotskyite Irving Kristol.

Kristol eventually became a power broker on the right, gaining access to significant funds from conservative organizations such as the Smith-Richardson Foundation, which he used to support the work of people like Jude Wanniski, who essentially invented the Republican obsession with tax-cutting. Kristol was also given a column on the conservative editorial page of The Wall Street Journal, from which he dispensed valuable political advice on how Republicans could defeat Democrats, both electorally and ideologically.

By contrast, there is little, if any, outreach from Democrats or progressives to the growing ranks of “Never Trumpers”—former Republicans who have abandoned the GOP and are among Trump’s fiercest critics. As was the case with former Communists, these apostates understand the vulnerabilities of their previous allies much better than their new allies do. The minuscule Lincoln Project, a home to Never Trumpers, has clearly gotten under Trump’s skin and become the frequent object of his Twitter attacks. Ironically, Irving Kristol’s son Bill Kristol has become one of the leaders of the Never Trumpers, to the point where he has become a sharp critic of not only the GOP but conservatism itself.

Underlying much of the Republican and conservative political success over the last 40 years is their embrace of the big tent—welcoming all who are willing to support their candidates and agenda, even if it is only on a single issue. The right understands that once you have entered the side door of the tent because of some narrow concern, such as abortion or opposition to gun control, it doesn’t take too much effort to persuade you to support the conservative agenda on other issues, such as tax cuts or restricting immigration.

Democrats don’t really embrace the big tent; indeed they often seem to have difficulty accepting some of those who have always had at least one foot in the tent, such as Bernie Sanders. Progressives generally don’t engage in outreach to those who may only agree with them on one issue, seeing them as an enemy on every other issue rather than a potential convert.

Biden will probably win in November. But undoing all the harm that Trump and the GOP have wrought will take several election cycles and determined leadership. Democrats need a long-term strategy of building up their base and winning over some of those who have not historically been part of it if they are to be successful.