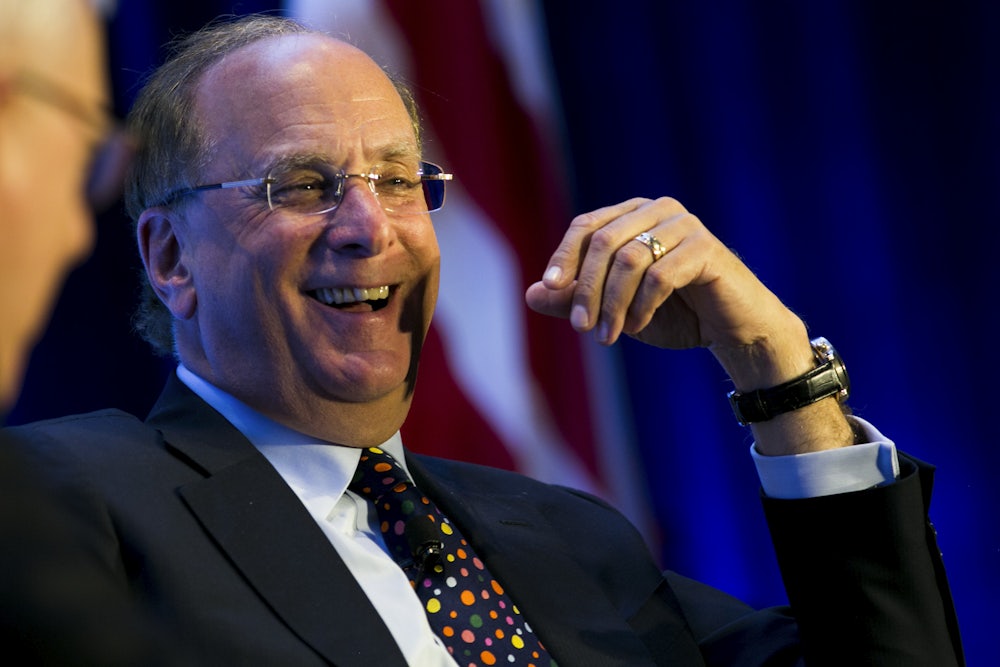

BlackRock is having a very good pandemic. The world’s largest asset manager has been tapped by the Federal Reserve to oversee three expansive government debt-buying programs meant to stave off economic catastrophe and is expected to make $48 million a year doing so. Of the exchange-traded funds, or ETFs, the Fed has purchased so far via this arrangement, about half have been BlackRock’s own, though the company will generously credit any income earned in those purchases back to the central bank. An even more full-throated merger of BlackRock and state could be on the horizon as CEO Larry Fink cozies up to Joe Biden’s presidential campaign, likely angling for a top Cabinet post. Whatever the result of the November election, BlackRock is poised to come out a winner.

The company, which manages nearly $7 trillion worth of assets, has positioned itself as the good guy on Wall Street, and its executives as a crew of mild-mannered money managers who understand the risks of the climate crisis and the importance of diversity. But those commitments, critics say, only extend so far into the firm’s day-to-day operations. BlackRock continues to fuel the climate catastrophe through its investments in fossil fuels and deforestation. Meanwhile, the company’s investments to influence Washington, through lobbying and campaign donations, have bought it friends on both sides of the aisle—thereby avoiding the kind of regulatory scrutiny to which a firm of its size would ordinarily be subject. As BlackRock amasses yet more power and wealth, it further ingratiates itself in both the U.S. capital and the global economy in ways that could prove difficult to unwind.

BlackRock has benefited greatly from the rise of so-called passive investment, which puts algorithms instead of human managers in charge of portfolios. Waves of pension and insurance privatization have been a boon, as well, something the firm has advocated for. Thanks in part to the lower fees passive management offers, most of BlackRock’s products track predefined indexes such as the S&P 500. The scale of these assets it has under management gives BlackRock a powerful voice in corporate boardrooms. Today, BlackRock and America’s other two major asset managers—Vanguard and State Street—together control 20 percent of the average S&P 500 company. BlackRock is the largest shareholder of the Spanish bank Santander and the third-largest at Apple, and equity stakes in smaller companies give it enormous sway over a stunning number of corporations the world over.

A report from the watchdog group MajorityAction found that BlackRock and Vanguard—the largest shareholders in 18 of the 28 carbon-intensive energy and utility companies analyzed—voted 99 percent of the time for the directors those companies proposed in 2019. Their votes were also key to killing 16 climate-related shareholder resolutions the same year that would have had majority support otherwise; both have voted in the past and more recently for such resolutions. (A spokesperson for Blackrock clarified that the company’s strategy in shareholder meetings revolves around the threat of voting against directors, not shareholder resolutions.)

BlackRock’s reach goes further than that of even other asset-management giants. Aladdin, its proprietary and ubiquitous risk-management platform, is, as the Financial Times puts it, “the central nervous system for many of the largest players in the investment management industry,” encompassing $21.6 trillion worth of assets from just a third of its clients—equivalent to 10 percent of global stocks and bonds. Daniela Gabor, an economist at the University of the West of England, told me that BlackRock has “become a monopoly provider of data infrastructure for every central bank that I can think of.”

So far, Aladdin’s focus on climate risks has been scant. In May, Blackrock announced that it had formed a partnership with the policy consultant Rhodium Group to integrate analysis on the physical risks from climate impacts (i.e., hurricanes) into Aladdin. Notably, this partnership does not appear to focus on the risks posed by the potentially trillions of dollars of fossil fuel assets that could be left “stranded”—rendered worthless—by some mix of market forces and government policy to transition to renewables. An analysis from the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis last summer found that BlackRock lost $90 billion on its fossil fuel investments over the last decade, 75 percent of which was from holdings in just four companies: ExxonMobil, Chevron, Royal Dutch Shell, and BP.

Despite all its holdings and data offerings, BlackRock has avoided being designated a “Systemically Important Financial Institution” (or SIFI, a.k.a. “too big to fail”) by the Treasury’s Financial Stability and Oversight Council, set up by Dodd-Frank financial regulations, which would require it to be regulated by the Federal Reserve. Perhaps this is because the company spent the better part of the last decade bombarding lawmakers, Treasury officials, and FSOC members with campaign donations and reports making the case as to why they should be excluded from Dodd-Frank rules.

Under the leadership of BlackRock co-founder and Vice Chairman Barbara Novick, who announced earlier this year that she’s stepping down, the firm argued that regulators should focus on the various activities of nonbank financial institutions, rather than the SIFI designation, which would subject it to a wider array of more stringent regulations. To observers, the company’s calculus here seemed pretty transparent: The FSOC doesn’t have any meaningful authority to regulate the activities BlackRock urged it to focus on. “All they can do in that space is look at the risks those activities and products potentially pose, write reports, and issue nonbinding recommendations,” said Gregg Gelzinis, a policy analyst at the Center for American Progress and former Treasury staffer.

Now, Gelzinis said, “Trump administration officials have basically proposed BlackRock’s approach to financial oversight.” The rules governing BlackRock have gotten even more lax just since the pandemic began. Until recently, PNC Bank held a 22 percent share in BlackRock, making the latter subject to some of the same oversight as banks; since PNC sold those shares off at the end of May, however, those rules will no longer apply. BlackRock will now face even less sunlight than it has before. Representatives Katie Porter and Jesús “Chuy” García recently introduced a bill attempting to rein in BlackRock and other so-called shadow banks, though it has yet to pick up much steam amid Covid-19 and an ongoing uprising for racial justice.

As BlackRock has ballooned, the gargantuan asset manager has curated an image as the kinder, gentler face of Wall Street, simply stewarding the money of retirees the world over. Fink, the CEO, emphasizes “stakeholders” over shareholders while being more outspoken than his peers on a host of matters—climate change chief among them. In advance of the World Economic Forum at Davos, Switzerland, in January (and after BlackRock was singled out for criticism by climate activists), Fink’s hotly anticipated annual letter to CEOs and other clients—signed by its full board of directors—urged a new path toward a more “accountable and transparent capitalism” that takes the threat of rising temperatures seriously. The rhetoric came with a host of pledges: By the end of this year, Fink promised, BlackRock will stop its actively managed funds from investing in companies that get 25 percent or more of their revenue from coal operations, enhance transparency over how it votes in shareholder meetings, create investment products that screen for fossil fuels, ask companies how they plan to navigate the climate crisis, expand its offerings of products screened for Environmental Social and Governance, and make all of its actively managed funds “ESG integrated.” Having voted against every shareholder resolution brought by the investor coalition Climate Action 100+ through 2019, Blackrock will now join it.

While these promises were praised by business journalists and even some climate groups, climate campaigners who had been tracking the firm were more skeptical. Even under the long list of sustainability measures BlackRock claims to be adopting, it will still be free to continue being a major investor in both fossil fuels and deforestation. A corrective, says AmazonWatch’s Moira Birss, is pretty simple: “Make fossil-free and deforestation-free the default. Right now, if you are a BlackRock client, the thing they’re offering you is full of climate-destroying companies. That’s a decision by BlackRock to make climate-destroying companies part of its default offering. It could make the decision to do the opposite.”

AmazonWatch is part of a coalition of green groups and corporate campaigners called BlackRock’s Big Problem, which since 2018 has drawn attention to the firm’s investments in companies fueling climate destruction through fossil fuels and deforestation. Working in partnership with Indigenous tribes in South America, AmazonWatch found in a 2019 report that BlackRock was one of the top investors in the agribusiness firms responsible for deforestation in the Amazon, with over $2.5 billion worth of shares of those companies. Under pressure, BlackRock has made vague commitments to engage with companies around deforestation and Indigenous rights, but tribes say they’ve seen few results.

Luiz Eloy, a member of the Terena people and a lawyer with the Association of Indigenous Peoples of Brazil, said in an email that BlackRock has “changed absolutely nothing to alter its investment strategy, which pours money into the very companies that brutalize us and take down forests on an industrial scale. Talk means nothing to us, not after so many of us have died and lost our homes.”

BlackRock’s transparency efforts have been piecemeal as well, activists argue. ESG remains a tiny portion of the products the firm offers, which it emphasized it would be expanding. To date the company has fully divested from companies that fell under its new thermal coal rules, which may not have been promising investments anyway. It has not specified the scale of investments it had in qualifying companies before divestment. A spokesperson confirmed Blackrock has no plans, as yet, to exclude either oil and gas companies or those involved in deforestation from its actively managed funds. Any changes to passively managed funds are still off the table.

In response to questions about the company’s debt-buying on behalf of the Fed, the spokesperson provided a statement that said, “BlackRock is acting as a fiduciary to the Federal Reserve Bank of New York. As such, BlackRock will execute this mandate at the sole discretion of the Bank, and in accordance with their detailed investment guidelines, in order to provide broad support to credit markets and achieve the government’s objective of supporting access to credit for U.S. employers and supporting the American economy.” BlackRock did not respond on the record to several other questions about the contents of this article.

Like most big companies, BlackRock gives generously to both major political parties, and despite his support for Biden, Fink has advised the Trump administration on everything from infrastructure privatization to the coronavirus. The firm has become a kind of safe haven for ex-Obama staffers, ready to feed future administrations with talent that hasn’t been tainted by stints at more despised companies like Goldman Sachs (the original vampire squid) or JPMorgan Chase. Fink himself may be angling for a position in a Biden administration. “We suspect,” The Wall Street Journal’s editorial board noted last month, “his foremost goal is to be Joe Biden’s Treasury Secretary.” Brian Deese—another BlackRock executive and former senior adviser to Barack Obama—has also been rumored to be in the running for a plum post. The group’s climate and energy work is headed by Rhodium partner Trevor Houser, who served in the Obama administration and as Hillary Clinton’s top adviser on climate and energy.

BlackRock’s influence doesn’t end in the U.S., though. It will advise the European Commission on the EU’s standards for sustainable investment, after having argued to weaken them. Members of the European Parliament and several NGOs have protested the decision and what they see as the troubling and growing role the company is beginning to play in the continent’s politics.

“Maybe the commission thinks, ‘If we give this mandate to BlackRock we’ll get the view from the market,’ because BlackRock basically is the market now,” said Benoît Lallemand, secretary general of the Brussels-based FinanceWatch. “That is how they build influence: Whether you like it or not, their opinion is useful.” And BlackRock’s contribution to Europe’s ESG discussion has precluded any talk of actively excluding investments in corporate polluters. Such rules could disincentivize investments in such companies. “The standards don’t matter when you have a regulatory regime that punishes” fossil fuel investments, said Daniela Gabor.

While BlackRock’s influence in Europe pales in comparison to its sway in the U.S., its more subtle maneuvering there might be a preview of what to expect from a Democratic administration that includes former BlackRock executives. The only sure result of letting BlackRock write the rules of a new green economy is that it’ll keep turning a profit, the planet be damned.