Over the July Fourth weekend, The New York Times’ editorial board unveiled a series of policy proposals to “move America society closer to realizing its ideals,” ranging from directing the Federal Reserve to target the black unemployment rate to ramping up the public funding of elections. The buffet of suggestions was particularly notable for the way it focused tightly on income inequality, through an Independence Day–themed lens of liberty, arguing that millions “lack the economic security that makes other freedoms meaningful.” But this opportunity for the paper to make bold suggestions fit for the crisis we face was squandered.

Some of the proposals were ambitious by the low standards we have come to expect from the Times, like a “baby bonds” program and doubling the minimum wage. Other key issues were given a hilariously drive-by treatment. The entirety of the editorial’s confrontation with the climate change crisis, which threatens Americans’ current and future economic security on a scale we can’t fully imagine, was limited to a single sentence: “Left unchecked, global warming poses an existential threat to the security and prospects of future generations.” There is no proposed solution to this coming apocalypse on offer, other than a passing mention of investment in sustainable energy. But no issue area was treated in a more baffling, and revealing, manner than health care.

It’s difficult to have a conversation about health care reform in 2020 without talking about either Bernie Sanders’s recent campaign or the larger push for Medicare for All, but the Times gamely made an attempt. The specter of Sanders’s two failed candidacies, with ambitious and universal programs to fight income inequality as their hallmark, haunted the editorial, but the paper chose to ignore the ghost at the feast: Though other former candidates’ proposals were mentioned, Sanders was left out. Former staffers, like Briahna Joy Gray, noted his absence from the piece; David Sirota tweeted, “Say Bernie’s name, damnit.”

Further than simply not mentioning Sanders, the editorial seemed to work hard not to mention his signature idea—single-payer health care—or even the idea behind it, of achieving universal health care. Here the Times might have more successfully separated the issue from the man: The simple fact of the matter is that single-payer health care was a winner on Super Tuesday as poll after poll revealed that there was enormous support for the policy among the Democratic party’s rank-and-file base. It would seem, however, that there might have been some internal confusion about what manner of health care reform the editorial was actually endorsing. When Times editorial board member Brent Staples advertised his team’s Great Works on Twitter, he billed it like so: “To repair America, start with housing and health care for all.”

The article never endorses health care for all. The closest it comes is noting that other “countries use a variety of systems to achieve better results, but those systems have two things in common: Everyone is covered, and the government seeks to hold down the cost of care.” The piece then says that increasing funding for “public health agencies” would be “one way to move toward those goals”—move toward, but not achieve.

Confusingly, this section of the piece is titled “With Housing and Health Insurance for All,” yet doesn’t express any support for policies to provide health insurance for everyone; it simply notes that other countries do that. (We know!) The editorial never endorses single-payer, a public option, magic beans, or any policy that would expand health insurance or care. In its final “checklist” of proposals, the piece circles back around to “Restore federal funding for public health agencies.” Even if you generously read the mention of other countries’ universal coverage as an endorsement of universal health care—which is a goal, not a policy to achieve it—you would have to note its absence from their ultimate list of policies.

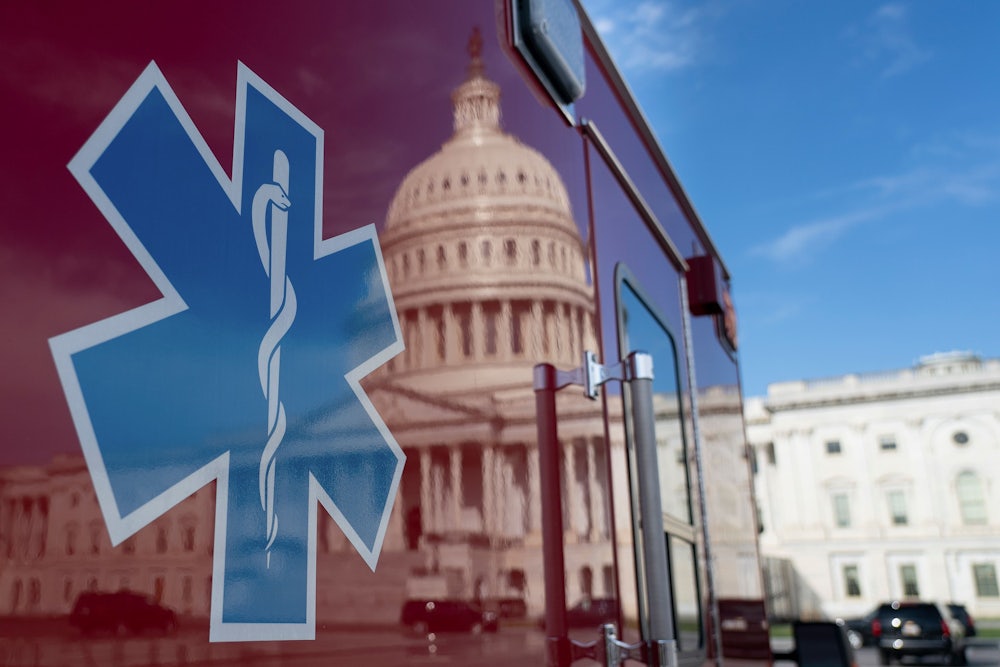

In the piece, the need to do something to improve America’s health care system is lumped in with a similar call to expand the benefit of housing. The two issues do have points of intersection, but the Times refuses to make either a connection between these ideas or make a plainly stated case that housing security is a health care issue. Instead, the authors tack the idea of increasing public health funding onto the end of a more detailed discussion of housing vouchers. This is a very strange treatment of an issue that was at the top of voters’ minds in the recent primary and, of course, remains there during the coronavirus pandemic. The truncated discussion of health care that readers are left with comes across as a poorly arranged compromise between members of the editorial board, who perhaps could never come to agreement on the issue of whether poor Americans deserve to die for lack of health care or not.

The only solution that earns space is increasing public health spending—an approach that is deeply inadequate to the problem at hand, almost beside the point. While it’s certainly the case that America’s public health system is in need of repair, the editorial board is making something of a category error, conflating the need to boost the ability of government agencies to coordinate responses to public health concerns with the larger matter of health care reform, which has more to do with the average American not being able to afford health insurance, the price of drugs, and the cost of hospital care. There’s no magic amount of money you can stuff into the coffers of public health agencies that will address, let alone solve, the larger crisis that has captured the attention of so many Americans. The common analogy for health care reform that maintains the private insurance status quo is that it’s like fixing the wiring in a house that’s on fire; increasing public health spending without even addressing the need to expand the health insurance franchise in any meaningful way would be like taking the hose and watering the plants instead.

A proposal to increase public health funding is, of course, welcome—we all want our tulips to thrive under normal circumstances. Only the most Trump-besotted Republican could live through the coronavirus pandemic and think, Yep, our public health response seemed to work fine. Public health institutions, which seek to prevent and limit illness and disease before they happen, are vital. These agencies, which combat everything from obesity and smoking to novel coronaviruses, are a crucial part of the mission to improve our citizens’ overall health and happiness; preventing disease is as important as treating it, and that cannot only happen in the doctor’s office.

But suggesting that increasing public health spending is a bold plan to help America uphold its promise as a nation—one that paves the way to the Times’ stated goal of “housing and health care for all”—is odd at best, and pathetic at worst. Public health spending is more like a thing that the government does so that we can basically call ourselves a country. It doesn’t move us much closer, however, to an idealized bastion of liberty and justice for all, where these nagging economic inequities are fully resolved. And as important as well-funded public health agencies are, they’re not the same thing as having a just and equitable health care system. The role of public health agencies is to support that system—and when they are built atop a broken, patchwork health care system the consequences reveal themselves quickly. You cannot be a shining city on a hill if half the city can’t see a doctor because it’s too expensive.

The New York Times editorial links to board member Jeneen Interlandi’s April op-ed about the gutting of public health in the United States, which noted that many aspects of our government’s failed response to the pandemic, including the lack of PPE and the mixed messages on social distancing, could “have been averted by a strong, national public health system, but in America no such system exists.” As she noted, even as spending on health care in the U.S. has ballooned, spending on public health has fallen.

Naturally, you certainly cannot fight pandemics with just a single-payer health care system, as the experience of the United Kingdom has shown. But you really can’t have good public health, from disease prevention to fighting obesity, without ensuring that everyone has not only health insurance but regular and free access to high-quality medical care. You can’t monitor disease outbreaks without being sure that people can go to the doctor if they get sick. And the health of the public is not the same thing as public health; people will still get sick even in a society with very good public health, and they deserve to be treated for free. This seems like a very basic point, but if the Times is going to suggest increasing public health funding as its singular solution to the gaping wound of America’s health care system, it needs to be said.

Some of the Times’ editorial board seem to grasp the urgency of improving health care beyond public health. Interlandi, for example, wrote an excellent op-ed last week about the insanity of tying health insurance to employment in this country. But suggesting public health spending as the one health reform you would pick to begin “the difficult but essential work of ensuring all Americans have the freedom to enjoy life and liberty, and to pursue happiness” is baffling. We have a much bigger problem than public health funding, and we just spent basically a whole year talking about the various solutions to that problem. It shouldn’t be a big ask to mention one of them.

The most generous explanation would be that the coronavirus pandemic has thrown our devastated public health infrastructure into such clear view that the Times simply forgot about all of our health care system’s pre-pandemic inadequacies. But these, too, loom so large that losing sight of them would be appalling, since tens of millions of Americans have recently lost their health insurance. Similarly, you could see this strange punt on one of the biggest issues in America as the board’s failure to reach consensus on universal health care. That said, the paper did come to a unilateral agreement to support baby bonds and universal pre-K.

So what gives? Has the Times given up on the idea of health care reform? Or, worse, does this reflect the reality that the truly gigantic changes to the health care system that we need are simply no longer on the table now that Bernie Sanders is out of the picture? Are we entering the Biden Era not just resolved to accept a watered-down public option but not to even talk about it anymore at all? It is a strange and troubling sign for health reform if The New York Times can endorse a $15 minimum wage and paid sick leave but not even muster support for a single proposal to expand health insurance coverage. Perhaps this simply reflects internal Times dissension to which we’re not privy. If that’s the case, it would be somewhat useful and informative for readers to know that the editors are still having a larger argument with one another—it would at least signal that the debate is worth having. The larger concern, however, is that their wan response to this crisis reflects a sigh of relief, in the most significant institution of elite opinion in the country, that they don’t have to think about health care reform anymore.