Viewers who tuned in to the Democratic National Convention a few weeks ago could have been forgiven for assuming that the spectacle they saw unfolding on their screens wasn’t so much the coronation of their own party’s nominee but rather a homecoming bash for Republicans. Democrats sure rolled out the welcome mat: Speakers at the event included GOP leaders like former Ohio Governor John Kasich and former George W. Bush officials such as Colin Powell and Christine Whitman.

The presence of the conservative figures was billed by media observers sympathetic to the Democrats as evidence that President Donald Trump’s time in office has divided the party and left decent Republicans out in the cold and without a home. What it may actually be revealing, however, is an ideological divide in the Democratic Party—one that might have significant implications if it’s given the reins to guide the country out of the turmoil of the Trump Era. To be engaged in an effort to rehabilitate the Republican Party while simultaneously reckoning with the damage it’s done to the country may be a contradiction impossible for Democrats to reconcile.

The convention’s GOP-laden lineup is just one example of what’s been a larger ongoing effort for the past four years to provide that rehabilitation to Bush and his cronies—an endeavor that comes despite the fact that Democratic Party orthodoxy just over a decade ago held that his administration was both a threat to the country and represented a force in U.S. politics that needed to be annihilated. But these once doctrinal beliefs have been thrown over in favor of a new interpretation of reality that relies on a premise that’s been repeatedly promoted by the Democratic Party and its mouthpieces at media outlets like MSNBC for the past five years: that Bush, and other GOP leaders before him, were fundamentally decent people with compelling, though ideologically wrong, ideas about what’s best for the nation—and that Trump is somehow different from them in his core beliefs and behavior.

That version of why old GOP hands were welcomed into the convention—and, increasingly, within the party’s institutions writ large—is one that’s appealing to a certain stripe of liberal who believes that Republicans are, at heart, decent Americans who just have a simple difference of opinion in the best way to ensure peace and prosperity for the country. It’s a view of politics that lends itself to a vision of America where a good argument and civil compromise can lead to a solution that works on some level for everyone. One such liberal who has articulated this belief in recent years—to the point that he’s made it a central point in his appeal to voters—is Joe Biden.

The message is becoming all the more acute as we head into the third decade of the new millennium. Bush, whose time in office set the U.S. on its current course of war, privatization, and financial ruin, is on the road to being absolved of his responsibility for the current chaos because Trump’s misrule has been a debacle sufficient to occlude the memory of those grievous sins. More than a decade since he left office with a historically abysmal 22 percent approval rating, Bush is today treated not just as a statesman but even as something of a cuddly old man, whose paintings of dogs and veterans and friendship with Michelle Obama have become the subject of fawning coverage in news media that elides the facts of his record.

But that record remains striking in its level of damage and destruction to American life and U.S. institutions. Bush started a series of wars across the global south under the rubric of combatting terror, codified torture and warrantless surveillance as U.S. policy, deregulated industries around the country with disastrous results, used the Justice Department to pressure prosecutors for favorable investigations, mismanaged a major natural disaster in Hurricane Katrina, and much, much more. All this was done in service of a right-wing ideology using the fear from the 9/11 attacks to drive an aggressive, messianic foreign policy and a domestic approach to lawmaking that masqueraded as “compassionate conservatism,” centering the redemptive language of Christian family values and using the president’s evangelical faith as a smokescreen for the cruelty of the administration.

Yet liberals remain incapable of letting go of the idea that the vision of conservatism offered by Bush still somehow creates a relevant contrast to Trump’s America. In the midst of the convention, as the Democrats celebrated their moderate tilt in the rise of Biden as the nominee, Daily Kos founder Markos Moulitsas tweeted that he was overjoyed the Democrats could finally retake the mantle of “faith, family values, and national defense” from the GOP. “I’m all about rubbing it in GOP’s face that our nominee actually goes to church,” said Moulitsas, who rose to fame and power within the liberal establishment for his criticism of Bush in the early 2000s.

For those who recall how Connecticut Senator Joe Lieberman’s rightward drift toward Bushian values during those years prompted the Moulitsas-led “Netroots” to become rabid bannermen of Ned Lamont, it was a head-snapping tweet. But the “rubbing it in their face” image speaks volumes. Still lost in a vision of politics that’s trapped in the past of 15 years ago, Moulitsas and his fellow Bush liberals see the GOP with whom they once sparred as a hypermasculine ideal and look at the rise of Trump as an opportunity for Democrats to finally shed their 97-pound weakling frame, read up on the Charles Atlas Dynamic Tension method, and become a buffer version of the GOP of two decades ago—in common cause with the same tough-talking Republican daddies they battled in previous decades.

The impulse to rehabilitate former ideological enemies like Bush is nothing particularly new for Democrats. The party has been angling for two decades to claim the anti-terror tough-guy identity from the GOP ever since the 9/11 attacks and the Bush doctrine’s subsequent aggressive reaction was used to kick electoral sand in Democrats’ faces by repeatedly using national security as a campaign issue.

Part of the Democrats’ latent desire to establish political common ground with the GOP stems from two devastating electoral defeats where conventional wisdom (though not historical reality) held that the party lost—in 1972 against Richard Nixon and in 1984 against Ronald Reagan—because nominees George McGovern and Walter Mondale, respectively, were too far to the left: in particular, too soft. The underlying logic of this Democratic Party insecurity complex extends from there to fold in the notion that the GOP has a preternatural grasp of the American psyche and that the U.S. is a fundamentally right-wing nation naturally suspicious of left-wing policies and social positions. This hoary version of reality is belied by years of opinion polling and movement politics, but that is irrelevant. Whenever elections are won by Republicans, rather than examine why there is a seeming disconnect between the views of the public and the electoral success of a party that works at cross-purposes to those views—an exploration that could yield something like voter suppression as a cause—Democrats put blind faith in the mythic power of the Republican working-class whisperer.

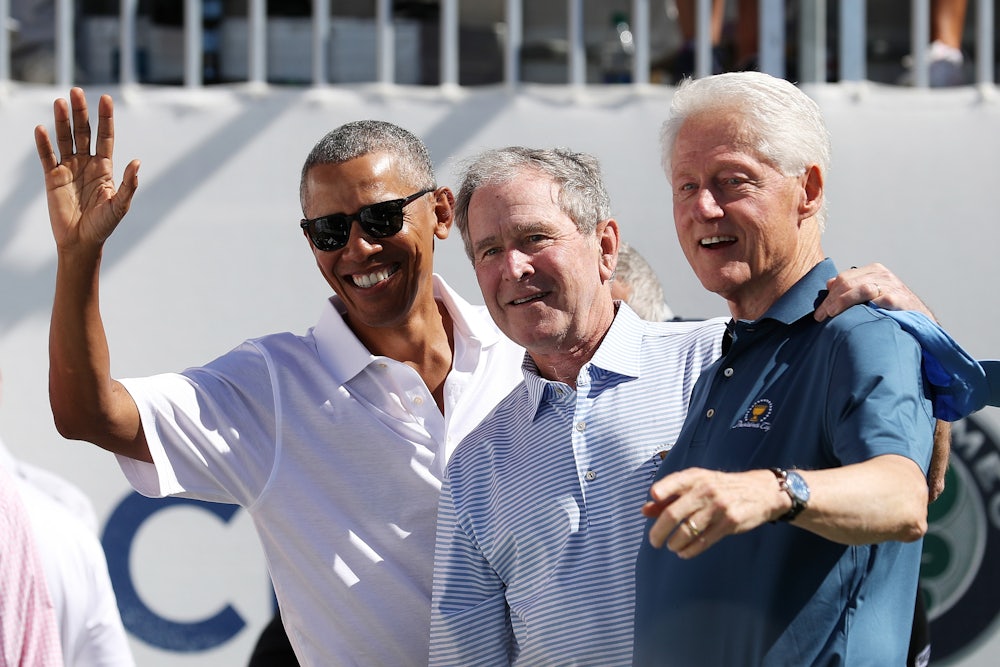

It’s a liberal ideal to find the good in one’s political enemies. During the Bush years, liberal commentators and politicians regularly referred with nostalgia to the then-president’s father, George H.W. Bush, and wistfully remembered the days when at least there was a rational actor you could work with in the White House. It’s astonishing that this impulse persists in the face of the right’s steadfast refusal to reciprocate these sentiments. All you have to do is tune in to watch Sean Hannity, Tucker Carlson, or any other member of the right-wing media pantheon: You’ll hardly hear them treat Obama and the Clintons with the same redemptive rhetoric.

For most left-leaning people, who have varying levels of attachment to the Democratic Party, the constant focus of party leaders on rehabilitating members of the Republican Party can be both confounding and frustrating. The Democratic Party’s case for rehabilitating Bush rests, in part, on the assumption that the most seamless means of obtaining electoral success is to convert enough fence-sitting Republicans to the center-left cause. That this assumption falls apart when it comes into contact with facts—only 5 percent of Republicans in a recent CBS News poll said they’d consider voting for the Biden-Harris ticket—doesn’t seem to matter. It’s simply been party orthodoxy—an article of faith that this is The Way To Win—for decades, despite all evidence to the contrary.

Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer’s infamous 2016 declaration that the party didn’t need to worry about blue-collar workers because of the mythical suburban swing voter—“For every blue-collar Democrat we lose in western Pennsylvania, we will pick up two moderate Republicans in the suburbs in Philadelphia, and you can repeat that in Ohio and Illinois and Wisconsin”—reads to the reality-based mind as the closest thing to “famous last words” that the 2016 election cycle provided. Yet somehow, this defeated belief has only been reinforced by an electoral strategy that appears aimed at a dozen or so opinion writers at The Washington Post and The New York Times who are also regularly featured on MSNBC.

The Comcast-owned network, which branded itself the home for Democrats and liberal-leaning Americans over a decade ago in the waning years of the Bush administration, has leaned all the way into becoming a home for the amalgamation of natsec liberals, professional class “Resistance” brunchers, and conservatives united in their disgust for how Trump conducts himself. Despite the fact the channel’s current presentation is still wheezily swagger-jacking the anti-GOP backlash that accompanied former President Barack Obama’s rise to power in 2007 and 2008, these days former Bush White House Communications Director Nicolle Wallace hosts a two-hour daily afternoon show on MSNBC. The channel’s daytime and primetime programming regularly features former Bush administration members and defenders such as GOP strategist and one-time Dick Cheney aide Steve Schmidt, former Bush speechwriter David Frum, former Weekly Standard editor and Iraq War cheerleader Bill Kristol, and many others from the era in the national security and intelligence fields, giving them a platform to spout off against Trump—and smuggle in right-wing talking points along the way.

Despite relentless criticism and questioning of the decision by commentators at the channel to uplift the voices of those who supported and in some cases even developed the case for the Iraq War, MSNBC and so-called Resistance liberals more broadly flatly refuse to change their approach. As the GOP convention raged, ignoring the pandemic; the hurricane; a year of pain, anguish, death, and social unrest, New York’s Jonathan Chait penned an essay inexplicably asking that the GOP be rescued from itself. Entitled “The Republican Party Must Be Saved From the Conservative Movement,” Chait’s article argued that Trump has exposed a “deeper rot” in the party, and “if any Republicans wish to alter their fate … the solution is both simpler and more radical than anything they have acknowledged: They must sever the party from the ideological movement that has controlled it for a generation and driven it into its present dysfunctional state.”*

The problem with this prescriptive approach, other than the logical responses—“Why save the GOP?” and “Can the Republican Party even be separated from the conservative moment?”—is that Chait is pushing for the Republican Party to change its approach to politics by leaving the conservative movement as it exists now behind and embrace “the sort of pragmatic center-right thinking being developed at the Niskanen Center and by some of the wonks at the American Enterprise Institute and a handful of other places.” It’s a perfect take for someone like Chait, who doesn’t realize that the “pragmatic center-right thinking” he presents as oppositional to his own views has been the dominant policy philosophy among the Democratic establishment for some time now. Meanwhile, leaving aside the quirksome Never Trumpers who’ve recently obtained high-profile media sinecures, the Republican Party, having painstakingly paved the road to Trumpism, hardly wants to be “saved” from it, now that this party-wide effort has reached its apogee.

This grand folly leaves anyone to the left of Bush-friendly liberals at a political disadvantage. But the strenuous effort to redeem Bush-era Republicans will ultimately leave ordinary Americans out in the cold, as well. Their most pressing need during a potential Biden presidency, after all, will be a path out of the coronavirus’s ravages, and the kind of politics that will be required to lead a post-pandemic recovery runs in the opposite direction from a project to redeem the GOP of the Bush era.

Should the Democratic Party continue to genuflect in front of a mythical, unattainable vision of a reasonable Republican, in the belief that such creatures can be won over to its side by the strength of its arguments and their love of country, it may never assert its own political alternative. But this fantasy of rehabilitation is durable and alluring: a television-inspired vision of men and women who place duty to country first, where all that’s needed to reach landscape-altering political compromises is a strong drink and some real talk over a winkingly forbidden nightly cigarette as patriotic strains crescendo on the soundtrack. Sadly, this is a delusion: Efforts to incorporate the GOP into the Democratic fold will only end in tears, with Democrats looking deeper and deeper into the abyss for answers and never realizing it has already consumed them.

* This article has been updated to better reflect Chait’s argument.