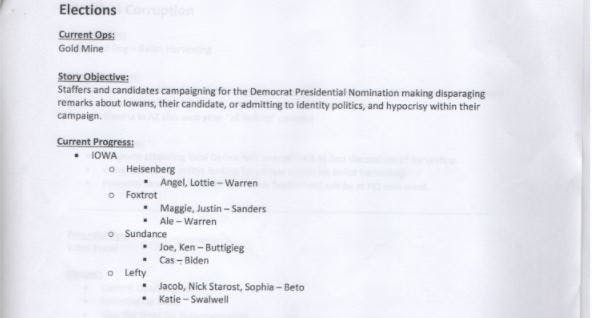

For Project Veritas, the 2020 Democratic primaries offered an embarrassment of riches. A historically large field meant plenty of targets against which James O’Keefe’s journalism-cosplay organization could deploy its signature tactic of getting low-level political operatives to say something embarrassing into a hidden camera, then hype a selectively edited video for maximum echo-chamber outrage. As we’ve already reported, based on internal Project Veritas documents, the group ran a sting, code-named “Gold Mine,” with operatives attempting to infiltrate the campaigns of Bernie Sanders, Elizabeth Warren, Joe Biden, and others, hoping to catch candidates or their staff members in a gaffe.

So far, so familiar—this is what Veritas does. Yet it’s worth looking at just who O’Keefe recruits to do it. To infiltrate the Biden campaign in Iowa, Veritas tapped an avowed Proud Boy, while a second operative aligned with the Proud Boys tried to infiltrate the Sanders and Warren campaigns. Project Veritas employs a Proud Boy who pleaded guilty to disorderly conduct for his part in a brawl following a speech by Proud Boys founder Gavin McInnes. O’Keefe himself has palled around with McInnes for years, and Veritas devoted an entire sting to defending the current leader of the Proud Boys.

The Proud Boys, for those not yet in the know, is an amorphous group of far-right men who claim not to be racists but promote the idea that white men are under siege; Proud Boys are frequently found in the company of avowed racists, and the Southern Poverty Law Center calls them a hate group. McInnes has repeatedly called for violence against left-wing activists, and the Proud Boys have been caught planning violent “rallies,” most recently in Portland, Oregon.

O’Keefe has always implausibly claimed that his organization is nonpartisan, but the proof is in the output: reliably right-wing, and more than a little bit fraught with disturbing racial tensions. This is to be expected. Project Veritas has always had a troubling history when it comes to race, and the specific overlap between it and the Proud Boys is increasingly out in the open. When President Trump says, as he did in Tuesday night’s debate, “Proud Boys, stand back and stand by,” he may as well be speaking to Veritas as well.

The Gold Mine document outlines how four Project Veritas operatives were sent to Iowa to infiltrate Democratic primary campaigns. One of them, code-named “Sundance,” targeted the Buttigieg and Biden campaigns. The document suggests he made contact with people named Joe and Ken in the Buttigieg camp and someone named Cas among Biden’s people. The Biden campaign did not recall having any interactions with Sundance, and his operation was apparently a bust—Project Veritas has released nothing on Biden from the primaries. At least, so far.

A source close to Project Veritas reveals that Sundance is actually Jackson Voynick, a 21-year-old from New Jersey who has declared himself a third-degree Proud Boy, according to the group’s arcane rules. In early 2017, he contributed his first article to Proud Boy magazine, after which he briefly contributed to Milo.net, the website of disgraced right-wing provocateur Milo Yiannopoulos. By the 2018 midterm elections, Voynick was working with Veritas, popping up in Georgia to cajole a pair of small-town poll workers into advising him on how to vote, a misdemeanor in that state. (Project Veritas hyped this as “Georgia electioneering.”)

In 2018, Voynick was also in Indiana, posing as “Jack McCarthy,” where he shot undercover video of Jill Donnelly, wife of then-Senator Joe Donnelly, and members of Donnelly’s campaign, in which they admitted that Donnelly downplays his support for unions to appeal to conservative Indiana voters. Donnelly’s defeat that year became another sad slide in Project Veritas’s pitch deck to its wealthy benefactors. As primary season began, Voynick made his way to Iowa for the Gold Mine operation. Cassandra Spencer, the Gold Mine operative who targeted the Warren and Sanders campaigns—and, based on an internal review of Biden staffers and volunteers, shadowed one of their campaign events just before the Iowa caucuses—called herself a “Proud Boys’ Girl” and retweeted Michelle Malkin saying “God Bless the #ProudBoys.” That means that, of Project Veritas’s four infiltrators, at least two declared support for the group.

The connections between the Proud Boys and Project Veritas are not always so covert. In October 2018, Jake Freijo worked the door at a Gavin McInnes event hosted by the Metropolitan Republican Club in New York City. Afterward, he was involved in a Proud Boys attack on anti-fascist protesters; police eventually arrested 10 Proud Boys. Charged with four counts of misdemeanor assault and one count of misdemeanor second-degree rioting, Freijo eventually pleaded down a single charge of disorderly conduct and was sentenced to five days of community service.

Just about a year later, according to his LinkedIn profile, Freijo began working as Project Veritas’s development officer, where he oversees charitable gifts of stocks, bonds, and other securities—an increasingly common anonymizing technique for the group’s wealthy donors. One of its most generous supporters, Robert “Dr. Bob” Shillman, appears to use this technique to avoid messy public disclosures of his patronage, eschewing more transparently partisan intermediaries like Donor’s Trust. Shillman’s $50,000 pledge to Veritas last year coincided with an equivalent and anonymous Fidelity Charitable deposit of $50,000 on its third-quarter deposit report. And tax records show that, in advance of the last presidential cycle, Shillman had moved over $4.97 million from his ample Fidelity Portfolio to his Fidelity Charitable Gift Fund destined for charities unknown.

It’s not clear whether Freijo’s bachelor’s degree in economics and years of experience as an NYC realtor qualify him to be a development officer, but there he is, prominently mentioned on the Veritas donation page.

It’s hard to imagine that O’Keefe’s organization has been unaware of Freijo’s well-publicized arrest and plea deal; in fact, just after Freijo’s case concluded in April 2019, the group unveiled a video defending the current leader of the Proud Boys, Enrique Tarrio, coyly described on Veritas’s webpage as “a man whose Chase bank account was shut down without [his] being given a reason” and “whose website sells provocative conservative merchandise.”

That website was 1776.shop, which, according to Slate, sold far-right merchandise (think shirts reading “Pinochet did nothing wrong,” for example) and charity bracelets said to help support the Proud Boys arrested in NYC. Numerous payment providers had stopped servicing Tarrio’s website, leading O’Keefe to profile him as a conservative provocateur who’d been “debanked.” O’Keefe homed in on Chase, claiming the company had never satisfactorily explained why it cut ties with Tarrio, who, the full video acknowledges, is “chairman of the Proud Boys and entrepreneur.” (Chase later disputed the report, saying it doesn’t close accounts based on political affiliation and that one of Veritas’s covertly recorded “sources” was not who the organization claimed.)

Gavin McInnes also appears in the video, part of a long-standing professional—and apparently personal—relationship between the Proud Boys founder and O’Keefe. The two have been on camera together as far back as 2013, predating the official founding of the Proud Boys in 2016. O’Keefe was honored as a “Proud Boy of the Month” in 2017 in the group’s official magazine; the two tried to crash the Tribeca Film Festival in the same year. McInnes showed up to O’Keefe’s American Pravda book parties in 2018. O’Keefe has appeared on McInnes’s show, as well as that of white supremacist Stefan Molyneux. In June 2020, both McInnes and O’Keefe appeared on The Alex Jones Show—thereby completing some sort of unholy right-wing conspiracy-mongering trifecta.

Behind the scenes, McInnes lives a short distance from the Mamaroneck, NY, headquarters of Project Veritas and, according to sources, frequently drops by to bask in the adulation of O’Keefe’s motley coterie of eager young conservatives. “I remember fellow employees being like, ‘I can’t believe I just met Gavin McInnes!’” one former Veritas member recalled, using a mock-giddy octave.

For his part, McInnes may see O’Keefe mostly as a tool of ideological and financial convenience. After attending a decidedly uncool May 3, 2014, housewarming at O’Keefe’s then-new condo in Jersey City, McInnes groused privately about how lame the party was. Recollecting it again on a podcast years later, McInnes could not help but rag on O’Keefe between bouts of praise, saying James was “a little on the spectrum,” “a little nerdy,” and more “like a work friend.” After losing to O’Keefe in a dance competition on the eve of Trump’s inauguration, McInnes told The New Yorker, “Fuck that guy. He just memorized a bunch of moves. I was dancing from the heart.”

On a personal level, James O’Keefe’s coziness with white nationalists dates back to well before his founding of Project Veritas. In 2006, O’Keefe was photographed at the Robert Taft Club’s “Race and Conservatism” conference, an event headlined by Jared Taylor, the self-styled academic white supremacist and publisher of American Renaissance, a journal devoted to, well, white supremacy. Reportedly, just about 40 people attended the event, so it’s not as if O’Keefe had accidentally wandered into the wrong ballroom. Around the same time, he added white nationalist Kyle Bristow to his Facebook friends, according to an archive of O’Keefe’s early online life—but he was already among his own. The event’s organizer, Marcus Epstein, was at that time O’Keefe’s friend and his co-worker at the conservative Leadership Institute.

Photojournalist Laura Sennett, who documented the event with anti-racist/anti-fascist researcher Daryle Lamont Jenkins of the One People’s Project, remembers seeing O’Keefe hanging with a “clique” beforehand that included Epstein and other future figures on the alt-right. O’Keefe appeared to be particularly chummy with Kevin DeAnna, future contributor to name-brand white nationalist Richard Spencer’s Radix Journal and founder of the short-lived, far-right campus group Youth for Western Civilization. “Marcus was setting up his literature table, and all his little buddies were kind of hanging out around him talking,” Sennett recalls. “DeAnna and O’Keefe were obviously chatting as friends. They were sitting right next to each other, chatting.”

Ascendant a decade later, Epstein and O’Keefe had a reunion of sorts when they both attended the pro-Trump art show “#DaddyWillSaveUs” put on by Milo Yiannopoulos in Manhattan (after a Brooklyn gallery punted the event, which had evidently been billed to the owner as “a satirical, Andy Kaufman–esque project”). “The Proud Boys had just got started,” according to Jenkins, who covered the show, “so this was, more or less, their first appearance: They chased somebody out; Gavin McInnes smashes his phone; that kind of nonsense—and O’Keefe was there. That was the last time I saw him.”

In Jenkins’s own footage of the incident, just after McInnes slams the protester’s phone onto the pavement, the Proud Boys founder can be seen delivering a fist bump to the late communications strategist for Project Veritas, Stephen Gordon. He then shakes hands with a cheering spectator named Matthew Tyrmand, a Polish nationalist who has served for many years as a conduit between the European and American far right, as well as a director on the Project Veritas board.

Through the years, O’Keefe and Project Veritas’s operations have featured, to put it charitably, a racial element. As Salon recounted in 2010, at Rutgers, he and his conservative friends held an “affirmative action bake sale,” charging whites more than their Black and Latino peers. In 2008, O’Keefe called Planned Parenthood and posed as a donor asking whether his money could go specifically to aborting Black babies. In “James O’Keefe Ambushes Republican Congressman Over Racist Bill” (2014), he claims a Congressman’s voting rights legislation “is racist because it excludes white voters.”

These are, of course, only the ideas that O’Keefe actually carried out. Perhaps just as revealing is an idea Project Veritas brainstormed but never executed. As revealed by CNN in 2010, the group once discussed whether it should create an altered video of civil rights icon John Lewis. After he and his colleagues walked through a crowd of Tea Party protesters, Lewis claimed he’d heard the n-word hurled in his direction; several colleagues backed him up. Andrew Breitbart didn’t believe it and offered up a $100,000 donation to the United Negro College Fund for proof that the epithet had been used. “This is 2010,” said media-savvy Breitbart. “Even a racist is media-savvy enough not to yell the n-word.”

Veritas, the CNN documents revealed, considered producing a fake video proving Lewis right. “The video evidence just needs to be simple, just Lewis walking by with a faint ‘n*****’ said in the background, yelled by someone there,” the document reads, spelling out the word entirely. “The video evidence would need to be sufficient to get by the potential fact-checkers at CNN who might analyze the video and audio.” Getting its tape on air, the Project Veritas crew argued, would undercut CNN’s credibility, suggesting the network would do anything—even accept as real an unvetted videotape secretly doctored by right-wing activists—to paint conservatives as racist.

Project Veritas has moved on to other things. The group’s recent releases have focused mostly on Covid-19 denial and undermining confidence in the electoral process, including targeting an older transgender man who voted twice, once under each of his two gender “personas.” From that rather sad example, Veritas sought to spin a whole tale of New Hampshire’s alleged failures to protect the ballot this November. What remains constant is that Project Veritas is not unique amid the flora and fauna of the conservative movement. This is what the right is becoming, increasingly up at its highest levels. Working with Proud Boys both openly and covertly, making appearances on racist podcasts, casually planning videos deploying the n-word—in its comfortable and long-lasting proximity to white supremacists, Project Veritas simply reflects the present and future of the Republican Party.