This week, Biden campaign manager Jen O’Malley Dillon announced that the campaign had $432 million in cash on hand. This is a truly absurd amount of money for any campaign to have. It is mental. Biden’s campaign is sitting on nearly half a billion dollars in cash, and it only has three weeks left to make use of it, the horrible possibility of expensive litigation following the election notwithstanding. And it’s not just the Biden campaign that has stacked that cheese: ActBlue, the site that allows Democratic campaigns to raise money from donors, announced that campaigns have raised $1.5 billion through its platform in the last three months, almost as much as the site raised in the entire 2018 cycle. Senate candidates like South Carolina’s Jaime Harrison ($57 million) and Iowa’s Theresa Greenfield ($28 million) have, in recent days, touted their own record-breaking amounts of campaign lucre.

This massive wave of small-dollar donations for Democratic candidates is good news for anyone who wants Democrats to win. But no one should get their hopes up that Democrats are seeing the light and moving away from the other kind of campaign cash—the sort extracted from millionaires and billionaires at closed-door fundraisers, lobbyists with an agenda, and corporations with only future profits in mind. No matter how many Regular People Bucks come in, campaigns will always seek cash from big donors too. It is the opposite of Three Stooges Syndrome: The door will always get bigger to accommodate whatever sort of money wants to enter. Small dollars will never crowd out the big bucks.

Biden’s campaign fundraising exploded in August, most notably after he named Kamala Harris as his running mate. In the 48 hours after the pick was announced, according to The New York Times, the campaign raised $48 million, with 80 percent of that coming from online donors. More than 50 percent of Biden’s fundraising total in August came from small-dollar donors, defined as those giving less than $200. But that leaves almost 50 percent that came from bigger donors, donors with more than $200 burning a hole in their deep pockets.

Biden’s campaign has still taken in millions from big donors, some of whom have given amounts in the multiple millions to his allied super PAC, Priorities USA. Like Hillary Clinton before him, Biden also has a joint fundraising committee with the Democratic Party that allows donors to give more than $600,000 in one check, circumventing the limit of $2,800 on general election donations to his actual campaign. More than 300 donors have given over $50,000 to the Biden Victory Fund, as of September. Those donors include James Murdoch, son of Rupert Murdoch; Laurene Powell Jobs, the billionaire savior of media whose company Emerson Collective keeps cutting and shutting down publications; Meg Whitman, who runs Quibi, the funniest company on earth; and David Zapolsky, the Amazon attorney who plotted to describe a rabble-rousing Amazon warehouse worker as “not smart, or articulate” and to make him “the face of the entire union/organizing movement.” The sort of cool chums you’d love to hang out with in your wine cave, in other words.

It is hardly surprising that there hasn’t been much discussion of big donors on either side in this election, save for the random outbursts of “SOROS?” from various members of the Republican Party, which are de rigueur among the party’s paranoiacs. There’s a lot going on in the world, and the president is an increasingly aggressive and unmoored racist. People feel strongly about getting him the hell out, and though the Republican Party is obviously beholden to big-money donors, it isn’t necessarily the most salient line of attack for Democrats when the Trump administration’s world-historical failure to contend with the Covid-19 pandemic is providing material. Also, Bernie Sanders lost: Democrats signaled a lack of interest in getting money out of politics when it made that choice.

But this issue is not going away. It will remain as long as we have elections, which is hopefully something that will happen again in this country; it may become more pressing after the all-absorbing issue of Trump has gone. It is undoubtedly true that this huge surge in small donations is largely due to Trump and the searing fear of another four years of misrule and the plain, pure hatred of everything he does. Such is the power of the #Resistance mindset. Absent that spark, small-dollar fundraising may suffer in 2022—not universally, and not inevitably for any one campaign, but campaigns will have to work much harder to earn the same dollars they do this cycle. (Campaigns that invest in their lists, instead of sending their donors increasingly deranged or outright misleading emails that turn them off from donating in the future, will do better.)

Next cycle, Democrats will have to raise money to compete with the always well-funded Republican Party, with its built-in advantage with the capitalist class, but without the demonic Trump to fundraise against. Democrats may have to promise “policies” that “actually help people,” for example. The party’s progressive-to-left base has always valued campaign finance reform, even when its attention is taken up by more pressing issues. Nevertheless, it’s a difficult topic to maintain energy around, partly because few candidates actually care about getting money out of politics more than about getting themselves into office, and partly because it is hard to imagine overcoming the problem without massive reforms to our democracy, like getting a constitutional amendment to overturn Citizens United. (Though the “massive reform” clause is true of almost every policy liberals want.)

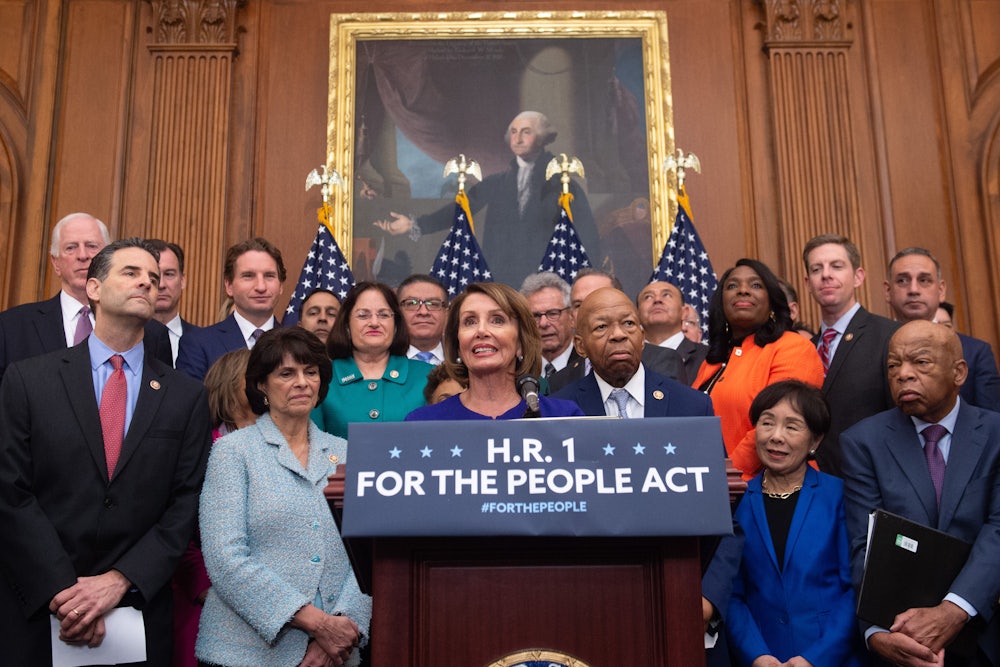

This Congress, Democrats did propose a bill that would have addressed campaign finance. In fact, it was their first bill, HR 1, which sought to establish a small-dollar matching program, in which candidates could receive a six-to-one match for donations up to $200. But the act, even as passed in 2019 with no belief it would ever actually be enacted, limits the program’s effect on big money in politics. For presidential elections, candidates would only be able to receive a maximum of $250 million in public funds, which is nowhere near enough to compete in today’s elections: Joe Biden raised $365 million in one month this cycle; in 2016, Hillary Clinton’s campaign and allied super PACs raised over $1 billion. It would not limit donations to the national or state parties, or to super PACs, though it would ban the joint fundraising committees that Biden has used so effectively.

Nothing at all will happen without Democrats in Congress providing the momentum. The majority of them don’t seem inspired to move on campaign finance reform, even with this surge in small-dollar donors providing a window into an alternate future. There is a difference between campaigns that raise a lot of money from small donors and campaigns that only raise money from small donors. When a regular person donated to a candidate like Bernie Sanders or Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, it was a sort of pact: The donor spent their money so that this candidate wouldn’t have to cozy up to big monied interests, in part because they believed these particular candidates would abstain from the practice. Barack Obama’s campaign was, at the time, arguably the most remarkable small-dollar-funded effort ever, and its rejection of lobbyist money was an explicit part of that message: It was he, not a Republican, who first raised enough money to reject public financing for his presidential campaign.

What Barack Obama actually did was raise a huge amount of money from small donors while also raising a huge amount of money from rich people. You can argue whether this constituted some sort of promise to donors that was broken, but it was, to put it mildly, different from what Bernie Sanders did. And Obama’s is the model that candidates like Joe Biden, Pete Buttigieg, and Beto O’Rourke have sought to emulate. It is an entirely distinct model from that of the insurgent left candidates who entirely reject the elite fundraising circuit, and whose policies would mean they’d struggle to find sympathetic audiences on Wall Street regardless.

This doesn’t mean that there aren’t millions of people out there, with hundreds of millions of dollars to give, who don’t care and will support Democrats even if they also take big corporate money. What it does mean, however, is that this incredible surge of small donors doesn’t portend any sort of departure from the big-dollar fundraising model upon which Democrats have relied. Democrats who defend the party’s use of shady conduits like super PACs and dark money nonprofits, or the general practice of sweet-talking rich people for cash, always claim that to forswear these free-flowing sources of campaign loot would be tantamount to “unilateral disarmament.” This election has provided evidence that there is actually plenty of money to be had in small donors, and that there are many other alternatives at hand besides making a compact with the moneyed elite. They know this: They just don’t care.