Even the prospect of the government cutting Americans no-strings-attached $2,000 checks seemed, as 2020 ended, to send certain moderates and liberals into a state of mild panic, as they imagined the funds falling into undeserving hands.

Larry Summers, the economist and recurring villain of modern Democratic presidential administrations, was quick to weigh in with some absurd fearmongering about the checks overheating the economy, as though too many people spending too much would cause the 1970s to happen all over again. More representative of the opposition to the proposal was Catherine Rampell, an economics and policy columnist for The Washington Post, whose objections at least tried to appeal to liberal senses of fairness.

As she put it, in a couple of columns, the problem was one of efficacy. The checks would simply not be as practical as more targeted proposals. People who don’t actually “need” the money would get it anyway—so shouldn’t Congress focus instead, she asked, on “additional weeks of expanded unemployment insurance”? Alas, she concluded, “a growing contingent on the left seems to prefer less targeted, more universal programs.” She didn’t seem interested in exploring why the left might favor such programs.

Rampell was wrong on the policy, anyway. The $2,000 checks would’ve been (and still would be) a good idea, both in terms of politics and even on purely technocratic grounds, as Ryan Cooper ably explained last week. Even the argument that Democrats were being forced into embracing a suboptimal policy because of the influence of their unsophisticated left wing is dishonest and absurd. The enhanced unemployment benefits Congress first enacted last March should never have been allowed to expire, but they did. President Donald Trump did not go on television to demand a lengthy extension of the Superdole—he demanded $2,000. Once he did, forcing various congressional Republicans to sign on to that demand as well, $2,000 checks became the realistic and achievable option.

Less interesting to me than the technocratic merits of the checks, though, is the unease the proposal has created in its detractors, including even ostensibly Keynesian liberals like Paul Krugman. These pundits generally objected to the plan on the grounds that there might be some other, more targeted way to jump-start the economy; they never really engaged with the fact that these “better” proposals had no hope of being signed into law with a president who seemed intent on blowing up any deal that didn’t include the checks.

One could argue that the liberal rejection of $2,000 checks was rooted in an instinctive distrust of any idea associated with a Democratic left that these thinkers consider unserious; or in the fact that they automatically suspect anything Trump supports; or in their neoliberal aversion to the prospect of Americans getting used to universal benefits (despite the fact, often papered over by these critics, that the checks are very much means-tested); but I think a lot of the criticism of the proposal can be traced to many years spent observing and participating in a purely resentment-based politics. In this vision of governance, every proposal is analyzed not in terms of how many people it can help but in terms of how mad others would be to see those people helped.

That calculus helps explain a number of infuriating Democratic tendencies. It accounts for their cringing reluctance to support popular ideas, such as student debt relief, for fear of future Fox News segments about suddenly debt-free art majors having more disposable income for avocado toast. And when popular ideas do make their way into the mainstream, it’s why these Democrats feel around for some argument, however specious, that might torpedo the proposed plan, like saying that if we made public college free for everyone, Jared Kushner would simply attend Fresno State without paying his fair share.

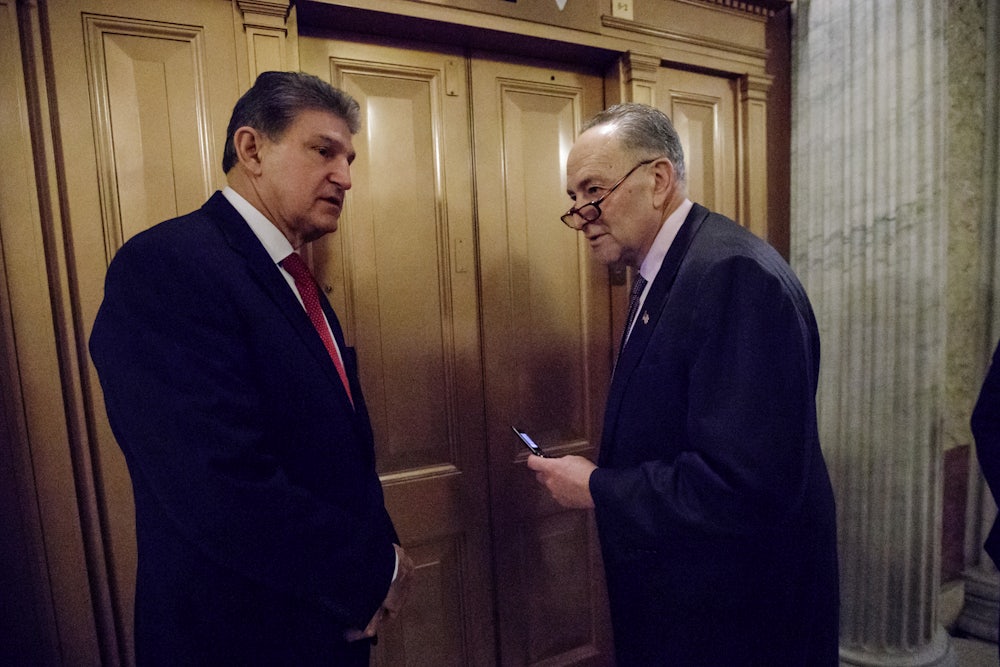

Given the pervasiveness of these moderate tendencies, it has been somewhat interesting to see soon-to-be Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer take up both the $2,000 checks and a fairly expansive student debt relief proposal. This is a man whose entire political philosophy revolves around imagining what an imaginary well-off suburban white Boomer couple might think. And he seems to have decided that the Baileys won’t blow their lids at seeing too many “undeserving” middle-class Americans getting a little relief from Uncle Sam. (In the coming months, we will see how serious he is about both ideas.)

Now that Democrats control Congress, we can expect another acrimonious debate over the design of the next round of stimulus, as liberal pundits and a handful of moderate politicians once more call for a package that distributes the money with greater precision. Joe Manchin, for one, has already said “absolutely not,” when asked if he’d support a round of $2,000 checks. As he told The Washington Post: “Getting people vaccinated, that’s job No. 1.”

I’m not sure how one precludes the other, but I would be happy to have Senator Manchin explain it to me. That would also give me an opportunity to explain to him how the same instincts that cause him and his moderate cohort to reject a large, universal benefit—the cowering reluctance to consider popular ideas simply because they might provoke a conservative backlash—are also having a deadly effect on state governments’ attempts to distribute vaccines.

At the most basic level, the distribution problem is the same as all the other failures of our government to respond effectively to the pandemic: decades of dismantling state capacity, utter indifference to responsive and effective governance on the part of our elected leaders, and the failure of most methods of democratic accountability. The vaccine distribution problem is the same as the testing problem and the ventilator problem and the hospital bed–capacity problem and the PPE problem. Our governments barely function, and few elected executives or lawmakers have much interest in making anything work correctly.

But the form that disinterest takes, when translated back into political rhetoric, is enlightening. In New York, where I live, the vaccine rollout has been dismally slow, considering the population and the supply allocated to the state. One reason for the delay, of course, is that the federal government has abdicated its responsibility for coordinating—or even offering to help the states coordinate—the vaccine rollout. But then some state leaders, such as New York Governor Andrew Cuomo, further abdicated responsibility for distribution, pushing it down the ladder to hospitals. (In doing so, he seems to have thrown out the mass vaccination plans, which would have relied on local health agencies for distribution, that the state put in place last fall.)

Cuomo has also given hospitals extremely arcane rules for determining who exactly is eligible to receive the vaccine. After an early news story about some clinics possibly violating those rules, Cuomo, smelling a brewing scandal, announced tough fines for any provider caught administering the vaccine to anyone who did not meet the eligibility requirements laid out in the state’s byzantine rules. He has now proposed making it a crime for a provider to administer vaccines to any ineligible person.

Meanwhile, he has also used threats to try to solve the larger problem with New York’s vaccination rollout: It is going incredibly slowly. Now providers are not only threatened with massive penalties for distributing the vaccines to any unapproved person; they are also threatened with massive penalties for not distributing vaccines fast enough. This has quickly become untenable. New York City’s public hospitals have already vaccinated every eligible worker, and they have, they report, thousands of doses now just sitting there, “without arms to give injections to.” The governor has already forced a hospital in New Rochelle to cease giving doses to municipal employees. On Wednesday, Cuomo had already faulted that hospital for only using about a quarter of its allocated vaccines. The state is threatening hospitals for not giving out the vaccine quickly enough and fining them for using it.

As a top Cuomo aide put it: “These principles are not inconsistent.” Indeed, they are not: They are both about seeking to look tough on undeserving people getting things, without having to be seen as directly in charge of a large logistical problem requiring lots of state capacity and administrative competence. Some of this behavior is just typical Cuomo (more than one observer has compared it to his handling of New York City’s transit authority), but it is not purely a New York problem.

The governors of Florida and California have similarly threatened providers that deviate from the state’s guidelines. Other governors have announced clearly politicized changes to those guidelines. In Nebraska, Governor Pete Ricketts made it clear that undocumented meatpacking workers are ineligible for the vaccine. In Colorado, Governor Jared Polis reversed his state health department and downgraded incarcerated and unhoused people on the state’s priority list. There were no public health rationales for those decisions; prisons and meatpacking plants are frequent sites of mass Covid-19 outbreaks, for obvious reasons. They were purely about avoiding backlash.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and state guidelines for vaccine distribution were decided carefully, but they were also seemingly decided under the assumption that the vaccines would be administered efficiently enough that no doses would be wasted. That is not happening. And considerations of who “deserves” the vaccine are now directly interfering with distribution.

Politicians are not actually mad about the undeserving getting something, or someone jumping the line. They are convinced that someone else, or many someones else, will get mad about it happening. They are in thrall to imagined future local news reports about undocumented meatpackers or imprisoned people receiving the vaccine ahead of a Good Taxpayer’s Grandma, and that fear, perversely, is making it significantly harder to vaccinate the Good Taxpayer’s Grandma. Here in New York, poorly allocated vaccine doses have already been thrown away. That is a fate far worse than a vaccine ending up in the arm of a supposed line-jumper.

A politics designed to avoid backlash would be more forgivable if our governing institutions and political leadership were effective. In the United States of 2021, they are just exacerbating the widespread incompetence. The alternative to $2,000 checks wasn’t a better-targeted stimulus—it was $600 checks. The alternative to handing out the vaccine more freely isn’t a more efficient rollout to the people who need it most—it’s perfectly good doses spoiling and getting tossed out. It’s time to err on the side of generosity. Give everyone vaccines and checks.