For decades, Democrats have tried to downplay any desire to simply give people cash benefits, seemingly fearful of being seen as doling out freebies to the lazy and undeserving—“welfare queens,” in the racist and sexist parlance that was so popular in the Reagan era. Then Joe Biden went down to Georgia with a promise of free money. It may be the reason his party now controls the Senate.

Checks in the amount of $2,000 would “go out the door immediately” if Democrats won both Senate seats in Georgia, Biden promised voters just ahead of the election. “Think about what it will mean to your lives—putting food on the table, paying rent.”

Framed neatly against the backdrop of a deadly pandemic and recession, it was a remarkably simple message: The Democrats are on your side, and you deserve something substantial for all you’ve been through. These are ideas that lie at the heart of Democratic Party principles. They’re also notions that the party has been running away from for decades, fearful that offering the people who might elect them something meaningful and tangible in return would be read by cynics as transactional, by conservatives as free handouts on the taxpayer dime.

Bill Clinton famously signed his welfare reform bill into law emphasizing “personal responsibility” and promising to “transform a broken system that traps too many people in a cycle of dependence.” But it was a contentious assertion among Democrats at the time, one that prompted the resignation of alienated Clinton officials such as Marian Wright Edelman and Peter Edelman, who has since argued convincingly that the welfare reform law destroyed the social safety net.

But in later years, Clinton’s step back became a retreat, as Democrats embraced pay-as-you-go spending policies and contended with every new policy idea being greeted with a But how will you pay for it? interrogation. And yet Democrats continued to be fearful of being perceived as “Santa Claus,” as Rush Limbaugh once labeled Barack Obama.

This year, those $2,000 checks have been the subject of torrid debate between Democratic economists and lawmakers, some of whom argue the checks are too big and would go to Americans who don’t really need the cash. (Even after Democrats nabbed those Georgia Senate seats on the back of the promised windfall, some economists, absurdly, implored Americans not to cash the checks when they arrived.)

Democrats only fully embraced the idea of doling out a fatter roll of banknotes after they received unexpected cover from President Donald Trump, who—seemingly in a fit of pique—beat everyone to the idea of making the stimulus payments more generous in December. A bill that would provide those $2,000 checks passed the Democratically controlled House with the president’s approval, only to die in the Senate when Mitch McConnell refused even to bring the legislation up for a vote.

That gave Democrats the attack they needed; Biden took it, ran, and came back with a 50–50 Senate. And now many Republicans, including Trump allies, are pointing to McConnell’s intransigence as the reason he’s about to lose the GOP’s Senate majority.

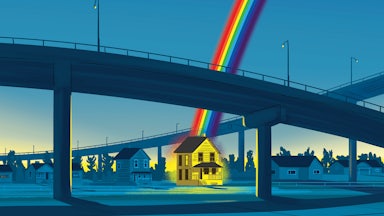

It’s been a long and winding road back to these simple principles. In fact, the idea of just giving cash benefits to people in exchange for their vote had strayed so far from anything that might be considered Democratic Party orthodoxy that it took Andrew Yang, an out-of-left-field candidate with no political experience prior to his surprisingly successful presidential run, to reintroduce the idea to the mainstream in 2020.

Politico described Yang’s rise as “crazy” and “a phenomenon hard to figure,” attributing his success to “strange political alchemy.” “Who knows how long it lasts?” they mused at the time. What got missed was the same thing that Democrats had been missing all along: the simple idea nestled in the core of his campaign—just give everyone $1,000 a month.

They also missed how a sturdy foundation for this idea had been laid in advance of Yang’s run for president, and the extent to which it had already gained considerable credence on the left, with the rise of charities that give money directly to affected individuals and the popularity of books like Annie Lowrey’s Give People Money. But Yang is perhaps the most high-profile proponent of universal basic income to date, and he was all over the idea while campaigning in Georgia for John Ossoff and Raphael Warnock.

“It has been incredible to see the tremendous rush of momentum for $2,000 cash relief,” Yang told The Washington Post. “People need help, and we have woken up to the fact that our government can deliver real relief if it chooses to do so.”

If people have woken up, it’s because Democrats have suddenly started ringing the bell—so much so that at times their rhetoric in Georgia put the candidates second to the money. This included campaign messaging from the candidates themselves: Two days before the election, Warnock tweeted a large image that said, “$2,000 relief checks now,” with a link to his website. In a different moment, an image like that might have capably served as a Republican caricature of tax-and-spend liberals.

When Yang first entered the presidential race, he and his idea of a “freedom dividend” were dismissed by mainstream Democrats, and political pundits used it to paint him as a joke. But his rise was a testament to how potent his idea was well before the recession started.

His hand has been considerably strengthened in these pandemic times. The $600 weekly unemployment sweetener that Congress seemingly walked backward into passing during its initial panicked response to the coronavirus crisis turned out to be an incredibly effective anti-poverty policy. It’s perhaps no wonder that simple promises of generosity were a potent political strategy in Georgia, where Ossoff and Warnock both improved upon Biden’s November showing. (Ossoff also outperformed his own Election Day numbers; Georgia’s jungle primary obscures such comparisons for Warnock.)

Naturally, many things have changed since November, chief among them Trump’s outspoken undermining of the election, which may have depressed GOP turnout. But turnout from Democratic, and especially Black, strongholds was especially high in this week’s runoffs. The most obvious reason why that was starts with a dollar sign.

Democrats may have learned the larger lesson: Rather than campaigning on triangulation in a battleground state, they can campaign on helping people, with the simple promise that if they get elected, there will be tangible rewards to come in the form of money that folds. Perhaps it’s such a basic notion that it wasn’t sexy enough for the wonks who have overthought themselves several hundred miles past the obvious: that money solves problems and giving people money is just the right thing to do. But Democrats’ recent successes suggest that it’s also a winning political strategy, as well. So even the cynics can take heart.