Last Friday, more than 400 people—lawyers, journalists, court staffers, gas and oil employees, and Indigenous citizens—joined a conference call that the fractious group believed might provide at least a temporary answer to a question that has now stumped two consecutive Democratic presidential administrations: What should be done about the Dakota Access Pipeline?

It could have been a defining moment for the Biden administration, one in which it could finally stake out a clear position regarding the nation’s continued dependence on fossil fuels and the extractive industry’s ongoing disregard for the specifics of tribal sovereignty. Likewise, the administration could have simply said it was OK with a pipeline operating in violation of federal law (as Dakota Access currently is, since it lacks a key permit for crossing the Missouri River). Instead, the lawyers representing the Army Corps of Engineering said only what they’ve said before—that they need more time to come to a decision.

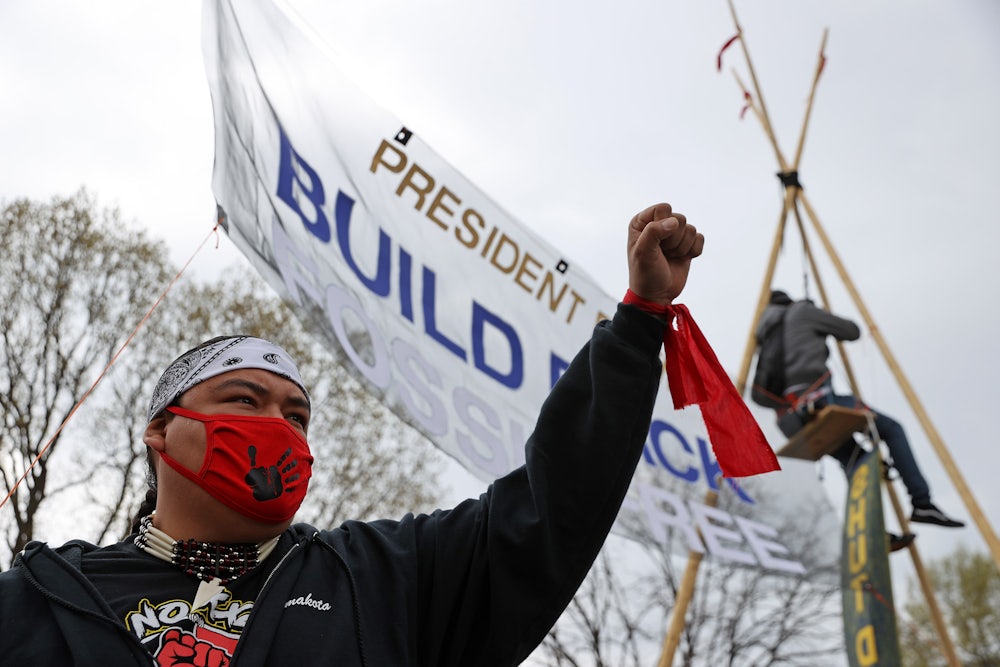

The Dakota Access Pipeline, known also as DAPL, was constructed under President Barack Obama, though his administration ultimately shuttered the pipeline. The about-face was the product of a campaign organized by the Indigenous citizens and allies at the Standing Rock camps, which protested the pipeline in the face of freezing temperatures, police water canons, and mass arrests. Shortly after taking office, President Trump revived the pipeline, along with Keystone XL, initiating a years-long court battle over whether the Republican administration’s agencies properly conducted an environmental impact statement.

The initial lawsuit, brought by the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe and the Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe, produced a ruling from the D.C. Court of Appeals last summer that found the Army Corps had erroneously issued an easement for the pipeline to run beneath Lake Oahe, a reservoir on the Missouri River, which runs through both tribal nations. At the heart of the challenge is whether the Corps adequately followed the National Environmental Protection Act, or NEPA. The federal law was designed, among many things, to measure the impact of a potential oil spill on the surrounding communities and wildlife and determine if any marginalized communities face disproportionate risk in the case of an infrastructural failure. In the case of DAPL, the environmental impact statement, in the view of Judge James Boasberg, failed on both counts, thereby nullifying the environmental impact statement and putting the pipeline—which has been operating since Trump took office—in violation of NEPA.

Energy Transfer, the company that owns Dakota Access, has opposed these rulings at every step, to little avail. In late January, a week after Biden’s inauguration, the D.C. Court of Appeals upheld Boasberg’s ruling. At that time, the court made a not-so-secret signal to the new administration that the Army Corps ultimately needed to make a decision as to whether the NEPA violations constituted a shutdown order. (Again, without an environmental impact statement that clears NEPA, the pipeline is effectively operating unlicensed.)

In February, the Biden administration’s Army Corps of Engineers asked the court for an extension—a request that, at the time, seemed reasonable given the White House and the Interior Department were just beginning a rash of consultation sessions with tribal leaders. The administration was also coming fresh off the cancellation of the Keystone XL pipeline and an executive order issued by the president that put a temporary halt on gas and oil leases on public lands. The political atmosphere as the administration was trying to get its Cabinet picks confirmed—Interior Secretary Deb Haaland faced a particularly loud Republican-backed opposition effort—wasn’t ideal for a DAPL battle.

However, when Friday’s court date arrived, those both in Indian Country and in the gas and oil industry expected a decision, one way or the other. Instead, Justice Department attorney Ben Schifman, citing the need for further consultation with stakeholders, said that the “Corps is in an essentially continuous process” regarding its assessment of the pipeline’s construction. Even Judge Boasberg, who last July ordered the shutdown of the pipeline before his ruling was overturned by a federal appellate court in August, admitted during Friday’s hearing that he was “a little surprised” that the Army Corps had not managed to land on a decision yet.

But perhaps those 400 listeners, Boasberg included, should have seen this coming. The day before, CBS’s Ed O’Keefe asked White House press secretary Jen Psaki point-blank whether the administration planned to let DAPL continue operating: “Our view is that we would look at each pipeline through—each individual pipeline separately—and do an analysis of the cost and benefits on the environment and jobs, which is my assumption would be happening here, so I don’t have an assessment of that, but we look at each of them individually,” Psaki responded.

Again, O’Keefe was not asking about a new fracking well in Wyoming. The pipeline in question here was—Donald Trump aside—arguably the defining political issue of 2016 and inarguably the most significant instance of Native peoples fighting for their sovereignty in a generation. The militarized police response to the protests drew widespread international criticism of America’s blatant pursuit of domestic oil dominance over the cries of Indigenous citizens and their governments. Friday’s hearing was planned two months in advance at the request of the administration. Yet, if one listened to only the Army Corps’s nonresponse and Psaki’s nonanswer, you would be hard-pressed to glean whether either had ever heard of the Dakota Access Pipeline before last week.

Most likely, the Biden administration does not want to incur further political heat from canceling a major pipeline and thus would prefer that Judge Boasberg rule on whether to issue an injunction and shutter DAPL—which he will now do. But it’s a conspicuous punt from an administration that has claimed to prioritize both climate and Native issues to an unprecedented degree. Both the United States and Canada, after all, could very well weather a DAPL shutdown without any major interruptions: Last Thursday, S&P Global reported that, should DAPL be closed down, either by the administration or the courts, the crude oil being mined from the Bakken Shale would simply be rerouted to its end destinations via other existing and properly permitted pipelines.

In response to a question of whether the White House has spoken with the tribes about DAPL since Biden assumed office, Jan Hasselman, an attorney at Earthjustice representing the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe, told reporters on a follow-up conference call after the court hearing that there have been several “formal and informal conversations” between the tribe and the Biden administration. He declined to speak on the details due to the confidentiality of those meetings. But both he and Standing Rock Sioux Tribe Councilmember Brandon Mauai noted that the existing flaws of the consultation process continue to define the legal fights over land and water rights in Indian Country.

“It really is a political question: Is the president willing to the stand by the promises he’s made and the rhetoric he’s espoused on tribal sovereignty and environmental justice?” Hasselman said. “Right now, we’re getting a disappointing answer to that question.”

The fate of DAPL, at least in the short term—the Army Corps will have the opportunity to redo its environmental impact statement—is now in the hands of Judge Boasberg, who will wait until next Monday for Energy Transfer to submit briefs on the economic effects of shutting down the pipeline before he makes his decision. After that, a court decision will be issued, appeals will be filed, and the pipeline either will or will not continue to operate in violation of NEPA. Meanwhile, what will remain unclear thanks to Friday’s dodge is how the Biden administration’s promises of reforming tribal consultation will hold up when tested on the public stage. Another question that urgently needs answering is whether this White House is remotely serious about pursuing a rapid transition away from fossil fuels.

This is, as I have written above and many others have noted, a difficult calculation. Canceling a pipeline as politicized as Dakota Access will undoubtedly carry its own costs. But the fight to stop DAPL—to stop Indigenous lands from being used as short-term cash grabs by corporations who won’t be around when the true stakes of their work is complete—is not just political. It is also extremely personal.

Less than 24 hours after the Biden administration passed the buck on DAPL, a more poignant, less expected piece of news started to spread across Indian Country: LaDonna Allard, a Standing Rock Sioux tribal citizen, passed away from brain cancer. As detailed in numerous obituaries and memorials, Allard was among the leaders of the Standing Rock protests, having helped found the first resistance camp established to block DAPL. While the movement was defined by the Indigenous youth that found their voice on the most public of stages, their work, like any of the work we as individuals or communities do, was built on a foundation established by elders like Allard, who understand the true stakes of the fights that came before them and the ones that linger after their passing.

It would have been poetic if Allard’s passing had been marked by an announcement that the pipeline she committed herself to stopping had finally been snuffed out. Instead, the communities and organizers she led are left to consider her words. “This movement is not just about a pipeline,” she wrote in 2017, in response to police forcibly clearing the Standing Rock camp. “We are not fighting for a reroute, or a better process in the white man’s courts. We are fighting for our rights as the indigenous peoples of this land; we are fighting for our liberation, and the liberation of Unci Maka, Mother Earth. We want every last oil and gas pipe removed from her body. We want healing. We want clean water. We want to determine our own future.”