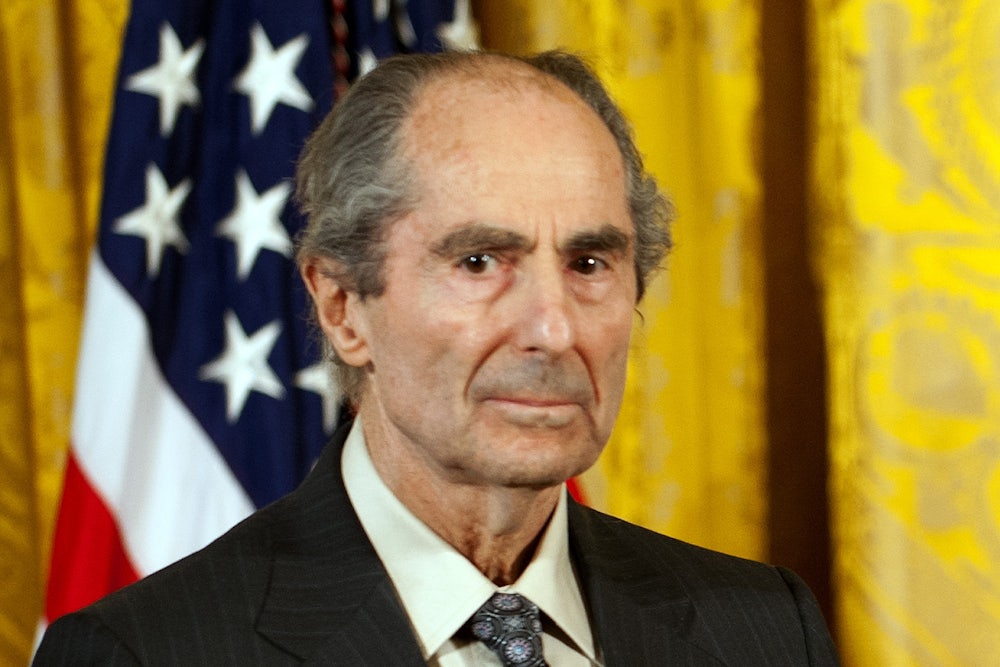

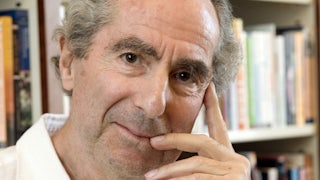

Celebrated author Philip Roth made a startling admission while speaking to a French interviewer nine years ago: He had asked his executors, the uber-powerful literary agent Andrew Wylie and ex-girlfriend Julia Golier, to destroy many of his personal papers after the publication of the semi-authorized biography on which Blake Bailey had recently begun work. His manuscripts, after all, were already housed in the Library of Congress; the Newark Public Library had his books, as well as many personal possessions. A control freak about his legacy and just about everything else, Roth wanted to ensure that Bailey, who was producing exactly the type of biography he wanted, would be the only person outside a small circle of intimates permitted to access personal, sensitive manuscripts, including the unpublished Notes for My Biographer (a 295-page rebuttal to his ex-wife’s memoir) and Notes on a Slander-Monger (another rebuttal, this time to a biographical effort from Bailey’s predecessor). “I don’t want my personal papers dragged all over the place,” Roth said.

At the time, Roth’s insistence that his executors destroy important biographical documents received little attention, and for good reason: In the same interview, Roth announced his retirement, ending one of the most important American literary careers of the postwar period. He died in 2018; Bailey’s biography, Philip Roth: The Biography was published last month. In the intervening period, few noted the Roth Estate’s plan to destroy these papers—it is mentioned in passing in a New York Times Magazine profile of Bailey and in a footnote in a Vulture interview, for example.

Much has changed in recent weeks. Last month, Bailey’s publisher, W.W. Norton, announced that it was halting promotion and distribution of the book after Bailey was accused of grooming, and in one instance raping as an adult, middle-school students he taught while working as an eighth-grade teacher in New Orleans in the 1990s. Soon after a publishing executive accused him of raping her at the home of a New York Times book reviewer in 2015, Norton announced it was taking the book out of print.

The fate of Roth’s personal papers took on new urgency in the wake of Norton’s decision. Last week, the Philip Roth Society published an open letter imploring Roth’s executors “to preserve these documents and make them readily available to researchers.” Efforts undertaken by Roth and his estate to control his legacy have backfired spectacularly. The best way to preserve his legacy, which has been damaged by the fallout from Bailey’s scandal, is to open up his papers to a wide variety of scholars.

Roth, of course, had other plans: Bailey was to provide the final word on his life and legacy. Even in this, the results have been disastrous. Bailey’s efforts to settle scores on Roth’s behalf, as The New Republic’s Laura Marsh wrote in a definitive piece, failed. The resulting work portrayed the author as a “spiteful obsessive,” while Bailey’s focus on Roth’s personal life overwhelmed a slight discussion of his literary output and other work, such as his advocacy on behalf of Eastern European writers. (One Roth scholar I spoke to compared reading the book to “watching Bridgerton—it’s all love and sex and lust.”) The subsequent scandals, moreover, have permanently tarnished the book’s reputation and only bolstered Roth’s own reputation for misogyny.

With so little having gone to plan, many Roth scholars are hoping to save the writer’s papers that have been slated for destruction. As scholar Aimee Pozorski, who teaches English at Central Connecticut State University told The New Republic, the effort is “about intellectual inquiry and protecting and diversifying the legacy of one of the most important authors in America.”

“In his fiction he writes about the complexity of human beings, of making mistakes, of getting people wrong,” Pozorski said. “In Exit Ghost he predicted this scenario—[in that book] Richard Kliman is a biographer who is not serving his subject well. One wishes that Roth could have seen into his work to understand that you need more voices, not fewer, as a result of the complexity.”

Jacques Berlinerblau, the Rabbi Harold White Professor of Jewish Civilization in the School of Foreign Service at Georgetown University, observed that Roth had spent his life creating a clique outside (and, in a few special cases, inside) the academy to control his legend. “Something very interesting happens with Philip Roth, and Philip Roth alone, wherein friends and fans with glorious perches in the media drive the narrative about him and the scholars—those pathetic figures—are completely sidelined,” Berlinerblau told me. “We’ve got to get control of this narrative because for three decades everything they know about Roth they know from his friends.”

“One thing I would love to see is scholars regain control, if they ever had it, of who this guy is, what he was saying, and what he was about,” Berlinerblau added. “I don’t know if that’s even possible, but preserving these documents is the first step.”

Bailey’s deal with the Roth Estate is complicated, unique, and still shrouded in mystery. Philip Roth: The Biography is copyrighted by both Bailey and the estate, for instance—a highly unusual arrangement, according to several publishing insiders I spoke to. The notoriously powerful (and just plain notorious) Wylie has used his muscle on Roth’s behalf before. Several years ago, the novelist spent more than $60,000 in legal fees to get a single line changed in an essay in a book of criticism written by Ira Nadel. When Roth subsequently learned that Nadel was working on a biography, he sicced his power agent on him. Wylie informed Nadel “that he didn’t have permission to quote from Roth’s work, nor would any of Roth’s friends and associates cooperate in any way.” (That biography, Philip Roth: A Counterlife was published in March; he also signed the Roth Society’s letter.)

The planned scope of the Roth Estate’s destruction is also not clear: It certainly includes Notes for My Biographer and Notes on a Slander-Monger, but it may also include a trove of other papers. A Times profile, for instance, observed that Bailey would have to return “hundreds of manila folders stuffed with archival material” to the Roth Estate, which would then decide what to keep and what to destroy. Roth scholars I have spoken to are adamant that Bailey’s conversations with Roth are his intellectual property and that he can do with them what he likes; they are keen, however, on preserving just about everything else, particularly the unpublished manuscripts and other materials that Roth instructed friends to send to Bailey as part of his research.

“Roth is a major enough writer, and these are important enough documents that not only shed light on what he was thinking about at the end of his life but on his entire life,” Roth Society president and Washington University in St. Louis English professor Matthew Shipe told me. “It would be a shame for only one person to have access to them and for them to be destroyed.”

Wylie and Golier, meanwhile, have been cagey about their plans and have offered no criteria for understanding how they will proceed. “There is a good chance we will destroy them,” Golier told the Times. “Andrew and I will decide when the time comes.” (Neither returned repeated requests for comment for this story.)

Norton’s decision to take Philip Roth: The Biography out of print was viewed as an opportunity to push the estate to commit to preserving Roth’s papers, as it would mean only a few thousand copies of a flawed, semi-official summary of the contents of these papers would survive. That effort has been complicated somewhat by Skyhorse Publishing’s Tuesday announcement that it had picked up the book and would be producing paperback and electronic editions in the coming weeks. It is understood, per multiple industry sources, that the strange copyright arrangement in Philip Roth: The Biography will also be in place in the Skyhorse edition. (Although there was a furor after Norton announced it was taking the book out of print, the book was always available. Amazon, for instance, is still selling new copies of the hardcover edition; the Skyhorse editions are likely to hit the market before stock is depleted.)

But Skyhorse’s acquisition of the book also presents an opportunity. It is a publisher that has gained a reputation recently for its willingness to publish “canceled” authors, most notably Woody Allen, as well as other unsavory characters, such as Alan Dershowitz and Michael Cohen. One industry source noted that Roth—and perhaps Wylie—would be embarrassed by the association.

It is, in any event, only the latest example of the Roth Estate’s mismanagement and the failure of Roth’s plans for his biography to work out as planned. These interlocking failures only energize those who have called the estate’s insistence on destroying Roth’s papers into question. “I think Wylie and Golier should respond to us,” Berlinerblau told me. “If they’re going to burn these papers, they should tell us why.”