The late-career essay collection can serve multiple purposes, none of which are mutually exclusive: It is a point of introduction to a new readership, one that may know the writer’s name but may be intimidated by their output, or simply want an easy place to start; it gives longtime readers a chance to encounter things they may have missed, little jewels for the completionists among us; and it may attempt to burnish the legacy of a writer in their twilight years who aims for one more chance at self-definition before their work is taken apart, posthumously, by literary wolves.

Not that Jamaica Kincaid’s legacy needs much burnishing—the Antigua-born novelist and essayist’s five-decade-long career is one that few writers would turn down. “In 1966, at the age of 17, with no money, no connections and no practical training, Elaine Potter Richardson left the West Indian island of Antigua, bound for New York and a job as an au pair,” a New York Times profile on Kincaid from 1990 reads. “She did not return until she was 36. By then she was Jamaica Kincaid, a respected author of fiction and a staff writer for The New Yorker, whose prose is studied in universities and widely anthologized.” In the 35 years since, her stature has only grown. I’ve assigned her work myself, though I first read A Small Place, her book-length essay published in 1988, only around 10 years ago. I imagine it has similarly served as an introduction to Kincaid for many people of my political persuasion—as searing an indictment of postcolonial politics as anything offered by Chinua Achebe or Wole Soyinka, and with the nerve to be funny, too. It’s the kind of essay that remains torturously relevant through the years; such trenchant critiques and general superlative skill with the written word (the Nobel laureate Derek Walcott, from that same Times profile: “The simplicity of her sentences is astounding. As she writes a sentence, the temperature of it psychologically is that it heads toward its own contradiction. It’s as if the sentence is discovering itself, discovering how it feels”) ensure that she will always find a place among the syllabi, the anthologies, the general regard of who is considered a “must read” among modern writers.

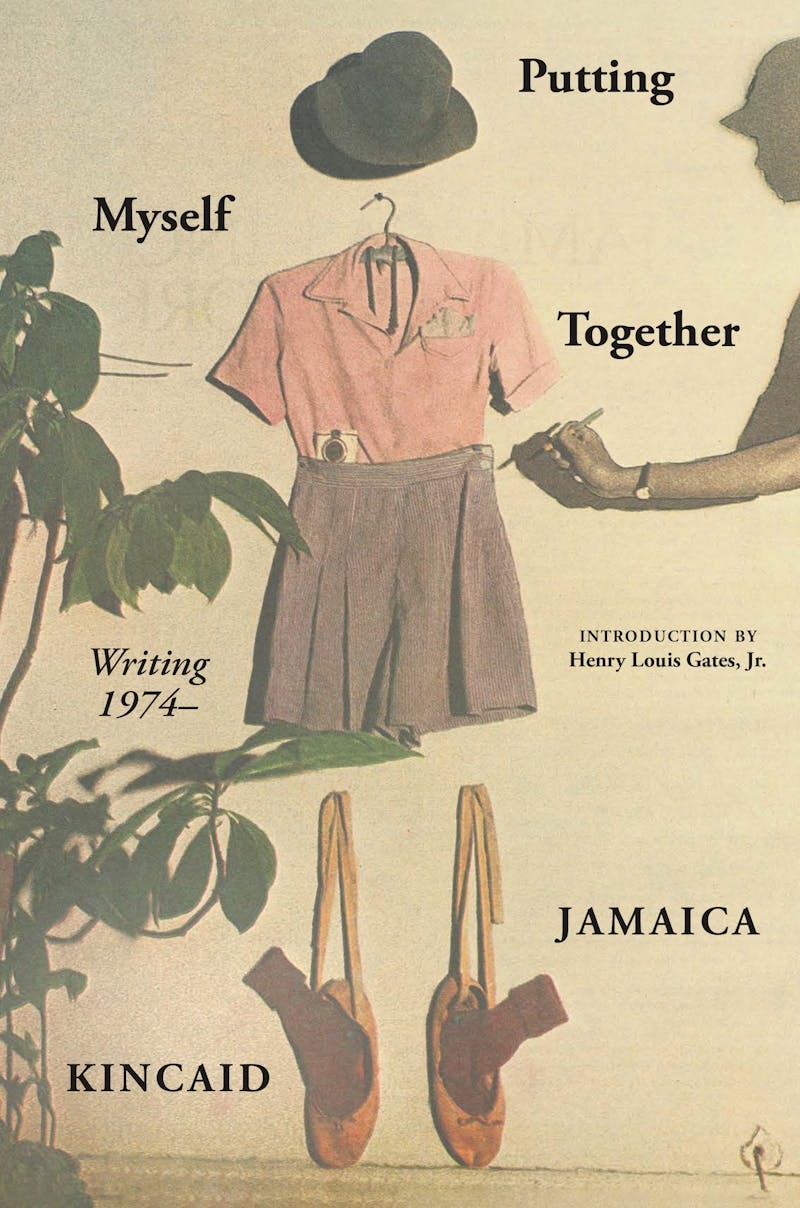

Kincaid’s new collection, Putting Myself Together: Writing 1974– is not charged so much with cementing any legacy (since that is well taken care of), though perhaps it will serve as a reminder of her stature. It isn’t a compendium of the greatest hits; this collection feels more like a fan service, bringing forth the work one might not have read unless you were there in the moment. Her time as a New Yorker staff writer contributing to its Talk of the Town column (previously collected in 2002’s Talk Stories) is well-documented lore, but Putting Myself Together reaches back to some of her lesser-known bylines (in The Village Voice, Ms., Rolling Stone), swerves into some lesser-known outlets (Transition, a magazine run out of Harvard about the culture and politics of Africa and the diaspora), and then situates them alongside her work for all the august names (Architectural Digest, Paris Review, Vogue, The New Yorker, of course) in a wide-ranging, panoramic view of the varied paths her career has taken, telling its own story of Kincaid’s evolution.

Having been introduced to Jamaica Kincaid as a fiery postcolonial critic and knowing her later career as a chronicler of her beloved garden, the essays that comprise the first part of this collection feel as though they were written by someone else. There’s a knowing, hipper-than-thou affect evident in the articles on Muhammad Ali, Patti Labelle, and Diana Ross, and she showed her humor early (describing the crowd gathered to watch the Ali fight at the Victoria Theater in a Village Voice essay: “No one looked as if they had gotten dressed up for the event. The closest thing to being glamorous anyone came was one man who walked around with an orange-colored Panasonic cassette player”), but is also mean in that way a twentysomething can be. (On Diana Ross: “Black people always say that they have one face for white people and when they are by themselves they are real. I have never for a moment thought that there was a Diana Ross more real than the one I could see.”) These are not essays of grand searching, but they don’t appear to have been reaching for much of anything at all—not that I would want anyone digging up writing from my early adulthood, for which the same could be said. Their inclusion in Putting Myself Together lends itself to a query: Does Jamaica Kincaid still like these essays, or are we to read them as folly? Did she want us to see them as great writing (they are fine for what they are) or as part of the collection’s own narrative structure—struggling toward greatness?

Whatever the case, they make the later works, in which Kincaid starts to hit her stride, feel that much more refreshing. A pair of essays from the late 1970s—“Jamaica Kincaid’s New York” and “Antigua Crossings: A Deep and Blue Passage on the Caribbean Sea”—originally published in Rolling Stone, show Kincaid developing the themes and prose style that will carry her through the next few decades. They focus on Kincaid’s most enduring subject: the daughter as object of subjugation, the mother as oppressor. “My mother sees my life in New York as turning against her,” she writes in “Jamaica Kincaid’s New York.” “In some way she is right.”

Kincaid is burdened by her mother’s unreasonableness (“I had just turned nine when it seemed to my mother that I talked so fast she couldn’t understand me anymore and that maybe the reason I did that was because I had something to hide. She said to me, ‘I better keep an eye on you because all fast chatters are liars’”), her lack of compassion (“A long time ago it was decided that a good profession for me would be nursing. I couldn’t stand the sight of blood, and when I would see someone ill I would sympathetically develop their systems. My mother said that I was just weak but that as I grew older I would grow out of it”), and her disappointment. In another essay included here, published in Harper’s in 2009, Kincaid begins: “Three years before my mother died, I decided not to speak to her again. And why? During a conversation over the telephone, she had once again let me know that my accomplishments—becoming a responsible and independent woman—did not amount to very much, that the life I lived was nothing more than a silly show, that she truly wished me dead.” And still, she loves her mother. The temptation is to say that is a complicated relationship, but Kincaid’s style, her matter-of-factness—those simple sentences that drew Walcott’s praise—suggest it’s actually less complicated than it appears. Kincaid loved her mother, and resented and hated her—no psychological inquiry needed. Her sentences need not meander around a point so ingrained in the fabric of her life.

Another fact: Kincaid hates England. It was her homeland Antigua’s colonizer and supplied the island with everything from Kincaid’s morning porridge to her father’s underwear, so it isn’t difficult to understand why; it’s as simple as the oppressive mother’s subjugation of the daughter. Kincaid shows little interest in drawing such parallels, though; when she writes of England, she would like for it to not be conflated with anything else. “I did not know then,” she recalls of her childhood schooling, “that the statement ‘Draw a map of England’ was something far worse than a declaration of war, for in fact a flat-out declaration of war would have put me on alert, and again in fact, there was no need for war—I had long ago been conquered.”

It’s by virtue of essays such as “On Seeing England for the First Time,” in which the above passage appears, and the aforementioned A Small Place, that Kincaid has become known, to some, more for her politics than her prose, a position I bemoan in solidarity. It was her politics that brought me to her, but Kincaid’s politics are not the totality of what makes her work worth engaging. What she is able to do with her seemingly simple language choices is speak what is true while capturing her desire for it to not be.

There is some filler in Putting Myself Together—forewords and introductions Kincaid has written—which in the aggregate sometimes feel like they are included primarily to beef up the book’s page count, rather than to chart a writerly evolution. For instance, “Introduction to Generations of Women,” while a fine enough essay, finds Kincaid again probing her relationship to her mother, but without much in the way of new insights that can’t be earned from reading the earlier entrants “Jamaica Kincaid’s New York” and “Biography of a Dress,” both of which are more formally inventive.

The collection’s thematic cohesion is most evident in its later sections, as the writings focus more on what has become her life’s great passion: gardening. (The first substantial mention of gardening here actually comes in one of the more explicitly political works, 1997’s “The Little Revenge From the Periphery,” as she unpacks the contradictions of Thomas Jefferson: “He had a garden and he had a farm—those things are not so much opposed to each other as they are just different: one is about necessity (the farm), the other is about how it looks and how the way it looks makes you feel (the garden).”) By this point, she has trained us to read her as a writer unencumbered by metaphor—a clear-spoken observer—and so we may want to read the gardening works as just that: writing about a practice which brings her solace. But in an essay from 2020, originally published in the “Book Post” newsletter hosted on Substack, she asks a little more:

But I was never really making a garden the way that most people, who are intent on making a garden and who will have ideas at the outset about what it should mean in some way that they might not even be conscious of; I was never really making garden in that way so much as I was having a conversation, a conversation with all the components, all the attributes, all the dangers, all the failures and pitfalls, all the moral and immoral dilemmas, all of the history of the garden and the way it has formed.

The garden is a point of connectivity—to Kincaid’s mother, to her homeland, to the history of race and class, to violence, to beauty. The garden is her writing life, meticulously cared for, though never without its regrets. And if the garden is here a metaphor for her writing life, what does Kincaid think will happen to it?

“A garden will die with its owner,” she writes. “A garden will die with the death of the person who made it.” True, unless you pass it on to someone who will care for it.