For a decade, Jonathan Greenberg, a social studies teacher at the Center School in Seattle, taught an advanced placement course for high schoolers called Citizenship and Social Justice. A broad-shouldered man with penetrating eyes and a warm manner, Greenberg brought in speakers to talk about their experiences of racism and invited his students to share, too. Sometimes, he separated them by race so they could consider questions more privately. In an exercise known as “affinity-based caucusing,” he might ask white students, “What’s the role of a white person in fighting racism at school?” Students of color, meanwhile, might share how they cope with discrimination they’ve faced.

Greenberg shaped his curriculum according to guidelines developed by Courageous Conversation, a group founded in 1992 to help teachers facilitate dialogues about race. The organization intends its discussions to be structured by four agreements: to stay engaged, to expect discomfort, to tell the truth, and to accept a lack of closure. Frank talk about encounters with racism, Greenberg believed, would help bring attention to the struggles of underrepresented populations at his majority-white public school, and help all his students link their present lives with the historical realities of race.

In December 2012, the parents of a white student in Greenberg’s class filed a complaint with the principal. Greenberg, they alleged, had not only created “an emotionally-charged classroom environment” and a “climate of fear,” he had fomented “racial hatred and prejudice.” The complaint made its way to the school district, and, within a month, Seattle Public Schools launched an HR investigation and told Greenberg that he could not teach the racism curriculum or a planned unit about gender before the investigation concluded. Besides the teen whose parents initiated the complaint, officials interviewed no students about their experience in the class. By mid-February, the superintendent wrote Greenberg that his lessons had created an “intimidating” atmosphere for the student and “disrupted the educational environment” for others. Students began circulating a petition demanding that the curriculum inspired by Courageous Conversation be reinstated; ultimately, they gathered more than 1,000 signatures. One day, as another teacher supervised Greenberg’s class, some students signed the petition. The parents who’d originally objected filed a second complaint, this time for harassment. Within months, the district transferred Greenberg to another school.

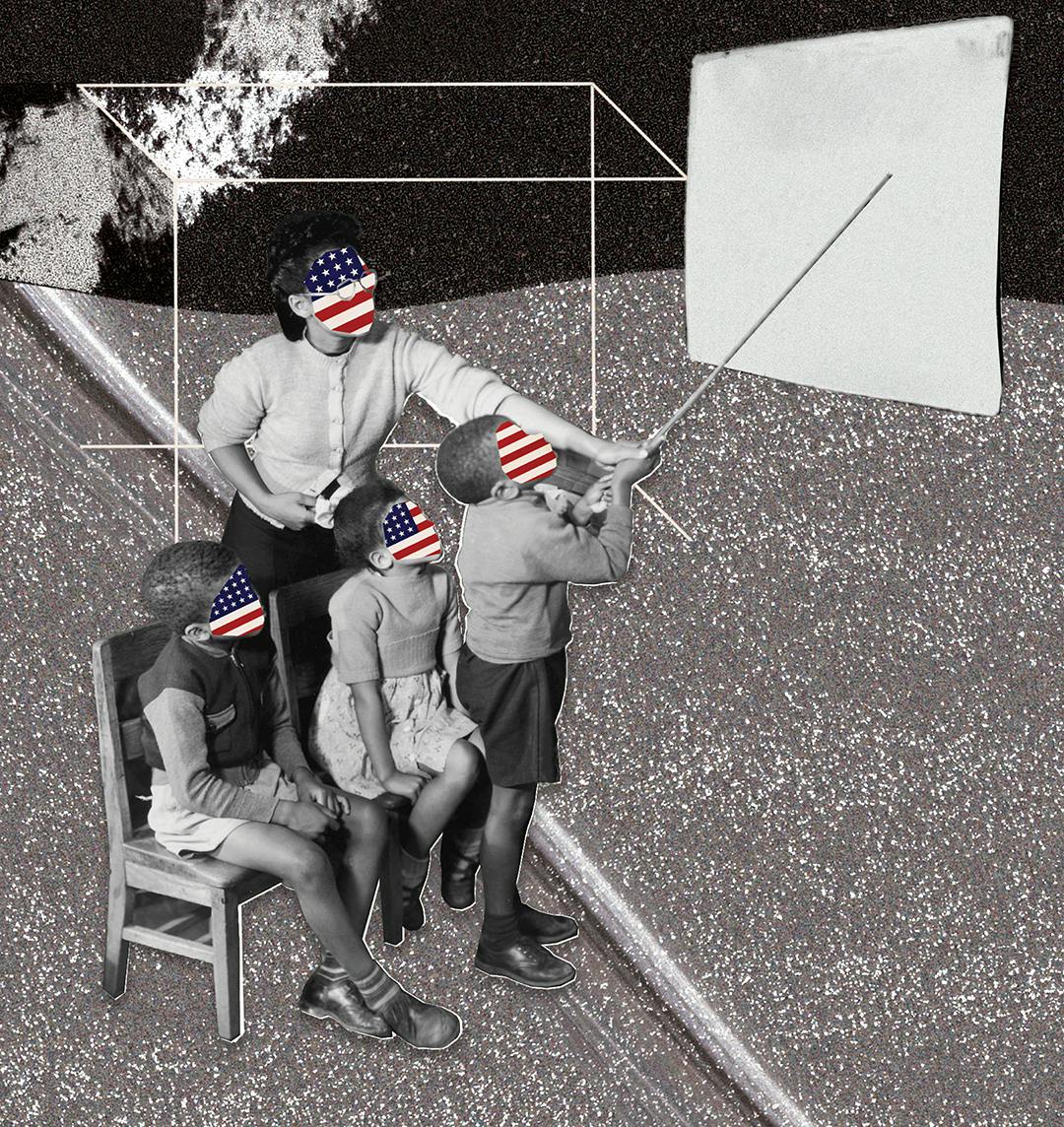

Nine years later, as states rush to pass laws banning “critical race theory,” a term that in popular usage on the right has come to mean nearly any curriculum that refers to systemic or structural racism, teachers around the country are wondering whether they’ll meet similar fates. By the end of January, more than 35 states had introduced bills or taken other steps that would restrict classroom discussions of race and gender, and at least 14 had passed laws or directives. The content of the laws varies somewhat from place to place. In Tennessee, for example, legislators banned 11 “concepts” from public school instruction. Educators aren’t allowed to promote “division between, or resentment of, a race” or suggest that individuals should feel “discomfort,” “guilt,” or “anguish” because of their race. In Iowa, lawmakers prohibit describing the state or the country as “systemically racist or sexist.”

For teachers, one of the most concerning aspects of the bills is their vagueness. Oklahoma’s law, for example, bans teaching the concept that one race or sex is inherently superior to another, but lawmakers declined to clarify how educators can teach about individuals who subscribed to these supremacist views. Texas’s law says any controversial issue must be taught “in a manner free from political bias” but doesn’t define what counts as controversial. Violating the new rules can bring about steep consequences: Teachers may be fired or lose their licensure; schools’ funding may be cut. Doubtless because the bills offer scant clarity about how one might comply, teachers have already begun self-censoring their lessons out of fear.

Their anxieties are not unfounded. In New Hampshire, the state’s education department created an online form to assist parents and students in filing complaints. The conservative group Moms for Liberty even pledged to pay $500 to the first person who “successfully catches” a New Hampshire teacher breaking the state’s new statute. Incoming Republican Governor Glenn Youngkin announced 10 days into his job that Virginia would offer a tip service for parents “to send us reports and observations” of teachers they believe are misbehaving. A group called Save Texas Kids—dedicated to “fighting CRT and any other form of woke politics”—emailed Dallas teachers asking for names of colleagues promoting critical race theory or “gender fluidity.” In December, Florida’s Republican governor, Ron DeSantis, proposed a bill that would allow parents to sue school districts that permit lessons allegedly rooted in critical race theory, and collect attorney fees for doing so.

For years, the school culture wars were waged over God and prayer, and how and whether to teach evolution and sex. But over the last decade, the fights have turned more toward how we frame our nation’s past, particularly how we characterize America’s histories of racism and colonization, and their relevance to today. In many ways, these debates are much harder to adjudicate; the law provides more clarity on the separation of church and state than on history curricula, and evolutionary theory offers more certainties than the vagaries of historical interpretation. For example, how should educators describe U.S. expansion of the West? Were the settlers bigoted imperialists or courageous pioneers? And is it possible for schools committed to anti-racism to embrace “color blindness,” or is that a contradiction in terms?

Public school theorists have long worried about the consequences of bringing heated matters into class. As far back as 1844, the famed educator Horace Mann warned against it. “If the day ever arrives when the school room shall become a cauldron for the fermentation of all the hot and virulent opinions, in politics and religion, that now agitate our community, that day the fate of our glorious public school system will be sealed, and speedy ruin will overwhelm it,” he wrote. Indeed, if there’s been one constant in the history of U.S. schooling, it’s the suspicion with which local communities respond when their teachers tackle controversial issues.

Parents’ fears notwithstanding, administrators stress that critical race theory is not taught in public schools; they are technically correct. As an academic field, CRT is a relatively obscure discipline that examines how laws and institutions harm or benefit people according to their race and relative power; its study is largely reserved to graduate programs. Yet parents who sense that change is afoot are also not wrong. Certain longstanding assumptions about identity and opportunity are being contested in K-12 classrooms around the nation—the same assumptions contested today in workplaces, in media organizations, and in the halls of Congress. The way these struggles shake out will have everything to do with how much control certain parents are able to exert in school districts and how well teachers can protect their autonomy.

Progressive groups and teacher unions have largely responded to critical race theory attacks with pleas that the public should trust educators to teach honest and accurate history. The appeal sounds reasonable enough, but what it means in practice is far from clear. Should teachers teach all perspectives on every issue? Is such a thing remotely possible within the constraints of a school year? What do young people need to know to thrive in a diverse, globalized, and democratic society? And who should get to decide?

On a Saturday morning in mid-November, just weeks after Glenn Youngkin won the Virginia gubernatorial election by campaigning on “parents’ rights” in education, an earnest and avuncular Colorado Springs high school history teacher named Anton Schulzki addressed a group of fellow teachers at the one hundred and first annual National Council for the Social Studies conference. Schulzki, the president of the council, acknowledged that the social studies curriculum has come under increasing scrutiny in recent years, particularly since The New York Times Magazine’s publication of The 1619 Project, a compilation of articles and essays asserting the centrality of slavery to any accurate story of the nation’s founding. “Time and time again,” Schulzki said, “teachers, administrators, and school boards have been accused of somehow indoctrinating their students.”

He noted the irony of history curricula dominating public debate around K-12 schooling when the hours of class time actually afforded to it—particularly at the elementary and middle school levels—have decreased precipitously over the last two decades. The primary result of the new rules passed by states and school boards, Schulzki argued, has been that teachers avoid certain topics altogether. But, he implored, they should try very hard not to. It is a time “for us to stand together in solidarity for social studies,” he said, “to use our collective voices in solidarity against ignorance, injustice, and indifference.”

The pressures around critical race theory shaped many other panel discussions throughout the weeklong virtual conference. One presentation—“Decentering Whiteness: One School District’s Approach”—explored the changes the Anoka-Hennepin School District, the largest in Minnesota, is making to the history curriculum to reflect the needs of its changing population. Like many other suburban areas, Anoka-Hennepin, which serves a large geographic region just north of Minneapolis that includes liberal inner-ring suburbs, conservative exurbs, and rural countryside, has grown markedly more diverse over the last 15 years; nonwhite students now represent a third of its student body. Some pockets of the district voted for Trump in 2020, others leaned toward Biden. Both the leftist Ilhan Omar and the far-right Tom Emmer represent parents from this area in Congress.

Dan Bordwell, the thick-bearded teaching and learning specialist in his mid-thirties who led the “Decentering Whiteness” presentation, described the work educators have done in his district since 2017 to incorporate more diverse voices into their social studies lessons. When students learn about Brown v. Board of Education, Bordwell asked, do they also learn about Linda Brown, the student who inspired the case, and her family? When they learn about the antebellum period, do they hear perspectives from Black lesbians? With the help of Keith Mayes, a historian of African American studies at the University of Minnesota, Anoka-Hennepin teachers worked to identify where they could “infuse” new discussions of race and racism into their curriculum, while still following Minnesota’s social studies standards, last updated in 2013. Anoka-Hennepin also established an honors-level Black history elective and ramped up professional development aimed at helping teachers incorporate narratives from underrepresented populations. It’s about “telling a more complete picture,” Bordwell explained.

Helping students see themselves in the curriculum, leaders in a growing number of school districts say, will lead to higher academic achievement and deeper learning for all. In 2019, Anoka-Hennepin issued an Equity and Achievement Plan, lending more support to the work its social studies department was already doing to bring perspectives of underrepresented groups to the forefront.

But not all families saw these changes as developments in the right direction. And over the last two years, as parents began mobilizing against the specter of critical race theory, much has changed in the district. In the Anoka-Hennepin Better Together Facebook group, which has more than 550 members, parents fulminate against excessively “woke” teacher trainings and other aspects of student learning. Krissy Erickson, the founder of the Facebook group, told me she started it after the principal of her kindergarten-age son’s school signed a “Good Trouble” pledge with other school principals in the Twin Cities metro. The pledge committed to “de-centering Whiteness” and “dismantling practices that reinforce White academic superiority,” such as tracking students. Erickson, who had never been involved in parent activism before, joked that “the mama bear just recently came out.” At a school board meeting in late August, she announced that she and her fellow parents were “done being bullied into silence” and criticized the “CRT-related ideologies” that have been presented to staff and “directly trickle down into students’ assignments.” Erickson stood “in full support of teachers,” she said, but insisted that “the only real privilege we need to reflect on is the privilege we all have to live here in the United States of America.”

Thousands of other, mostly white, parents across Minnesota have similarly been protesting proposed state social studies standards that for the first time would include ethnic studies as a core component for all students. The standards—which would take effect in 2026—reflect “a relentless fixation with Native American history” and replace “objective historical knowledge … with a fixation on ‘dominant and non-dominant narratives’ and ‘absent voices,’” according to a petition led by the Center of the American Experiment, a local conservative think tank. This past November, Anoka-Hennepin residents elected a school board member, Matt Audette, who ran on a fiercely anti-CRT platform.

Bordwell, whose emails have been subject to FOIA requests by suspicious members of his community, has felt the increased pressure acutely. He submitted the idea for his “Decentering Whiteness” panel in February 2020; had he crafted the pitch a year later, he said, he would likely have proposed a different name for his presentation. “We have teachers who are walking on eggshells worried that they’re going to have a picture taken by a student or parent, that they are going to be unfairly targeted for the work that they’re doing.”

At my request, Erickson asked other parents in her Facebook group what they make of teachers’ fears about retaliation. Some teachers, she told me, are “obvious activists who will stop at nothing to promote their own OPINION.” But she believed that most parents would be satisfied so long as educators are “presenting facts and multiple viewpoints.” Members of her group, she explained, feel that issues of race, sex, and gender have “been thrown at our children from every angle”; they want “to simplify things and get back to education and academia.” As a compromise, Erickson proposed making certain subjects elective, or providing families with a heads-up about unit discussions and allowing them to opt out if they disapprove. In this, she echoed a call common among the anti-CRT cohort, who argue that teachers should alert parents of any plans to include controversial subjects in their curriculum, and even let them review teaching material ahead of time.

If the members of Erickson’s group—and similar parents—are to be taken at their word that they would support the inclusion of multiple viewpoints, they should be reassured by the work of some nonprofit education groups aiming to help teachers tackle controversial issues. One such group is Close Up. Founded in 1971 initially to bring high school students on trips to Washington, D.C., Close Up encourages “deliberation” on heated policy questions as a way of helping students build consensus. A study of its model, published this past summer by professors at North Carolina State University and the University of North Carolina Greensboro, found that high school students felt more respected in classroom political discussions designed as deliberation rather than debate.

A class using Close Up’s approach might ask, for instance, what policies, if any, are needed to reform police practices. Students would read about the disparities between Black Americans’ encounters with the police when compared to other groups, explore different policy proposals to address the issue—banning the use of neck restraints, for example—and review the arguments supporters and opponents make for each idea. At the end, students would be asked to write about which proposals they favor, which they would change, and which they would reject, and could suggest other proposals.

At least in theory, it’s possible to imagine such an approach satisfying people across the political spectrum. But on certain deeply polarizing issues, such as rights for undocumented immigrants or the place for transgender students in school sports, some on the left have argued that it’s harmful even to have those discussions; normalizing certain perspectives, the thinking goes, can be destructive to the vulnerable people they’re about. And on the right as well, many parents find certain points of view too dangerous to debate; talking about transgender athletes, for example, legitimizes the gender categories these parents patently reject and believe could corrupt their children. Sante Mastriana, a curriculum design manager for Close Up, said the group doesn’t support deliberating on everything; certain topics, like white supremacy or the efficacy of fascism, are off limits. “There are certain arguments which we are not going to entertain as valid,” he told me. Of course, if some subjects are out of bounds, it’s impossible to claim that ideology doesn’t, at some level, govern the choice of study; some administrator somewhere is choosing what to include and what not to. Mastriana said that Close Up’s solution is to rely on multipartisan resources and facts. “Unless it’s the sort of argument that just categorically makes a supposition about the nature of things without actually providing any grounding,” he said, “then it is something probably worth addressing.”

Chris McDuffie, an eighth-grade civics teacher at Heathwood Hall, a private school in South Carolina, uses Close Up materials in his classroom. He likes their “fact-based, middle of the road” format. “I tell kids to wait at least three days, check at least three sources, and to enter a conversation with three pieces of information or three questions before they form an opinion about a current event,” he told me. “No one knows where I fall politically, and I pride myself on that.” But McDuffie, who has been teaching for 21 years, including 12 in public schools, acknowledged that it’s easier to tackle political issues in a private school, where he’s afforded a great deal of autonomy over lessons. When he worked at a public school, some administrators, wary of backlash, didn’t even support teaching current events.

Like the nonprofits, some state school board associations have been encouraging local school districts to better support educators teaching contentious issues, a risky move given the intense politicization of the National School Boards Association in 2021. Last year, the national group compared parents protesting critical race theory at school board meetings to “domestic terrorism,” which led 21 mostly GOP-controlled states to withdraw membership, participation, or dues from the organization. Nevertheless, in late November, in Loudoun County, the northern Virginia region that became a national epicenter of parents’ protesting CRT, school administrators recommended that their school board adopt a policy called “Teaching About Controversial and Sensitive Issues,” based on a model promoted by the Virginia School Boards Association.

Examples of such controversial topics, said Ashley Ellis, Loudoun County’s deputy superintendent for instruction, are slavery, colonization, immigration, and the Holocaust. “Schools are under more scrutiny for what they’re teaching,” Loudoun Now, a local paper, quoted Ellis as saying. “Our teachers have asked for support in how to approach these topics with confidence.” A spokesperson for the district declined to comment on the proposal.

Teacher unions, too, have been exploring ways to support educators who tackle controversial issues. The three million-plus–member National Education Association has been organizing to pass a model school board policy that affirms the value of Black and other ethnic studies courses and pledges to defend teachers who use materials “that incorporate diverse perspectives.” The unions have also been organizing to back candidates in school board elections. “We are preparing and training our educators to be involved in elections of those who have the power and authority to make the decisions,” Becky Pringle, the president of the NEA, told me.

But parents opposed to CRT have likewise stepped up their school board efforts. In 2021, the 1776 Project PAC, a national right-wing group, formed to elect school board members who are committed to “abolishing” critical race theory and The 1619 Project from public school curricula. The group backed 57 candidates across seven states, 41 of whom won. In 2022, its sights are set on 200 additional races.

Some of the current disputes over curricula can be traced to the beginning of the Obama period. The election of the nation’s first Black president led to new cultural and political backlash, including fights over how to teach about American identity in schools. As the education historian Jonathan Zimmerman has observed, critics began labeling ethnic studies courses as “divisive” and “un-American,” and by 2014, groups were lobbying against the College Board’s revised A.P. U.S. history course, which opponents alleged cast U.S. history in too harsh a light. For example, the revised guidelines described the idea of manifest destiny—the nineteenth-century doctrine that said the expansion of the United States throughout North America was both justified and inevitable—as “built on a belief in white racial superiority and a sense of American cultural superiority.” The Republican National Committee passed a resolution that year blasting the framework for its reduced focus on the Founding Fathers, the Declaration of Independence, and U.S. military victories. The framework “emphasizes negative aspects of our nation’s history while omitting or minimizing positive aspects,” the RNC said. (A year later, the College Board issued yet another revised framework, filled with edits that successfully quelled its conservative critics.)

Last spring, after state lawmakers began introducing bills banning critical race theory, the left-leaning Zinn Education Project sponsored a Teach the Truth pledge, garnering thousands of signatures from teachers. The National Education Association has its own Pledge to Support Honesty in Education. Both groups argue that CRT critics want teachers to avoid addressing topics like slavery and redlining, but conservatives insist that charge is a lie. Regardless, mainstream history textbooks do cover the nation’s disturbing history of racial violence better than they used to. A content analysis led by education historian Jeffrey Snyder found that leading contemporary texts depict in detail “everything from slave whippings and lynchings to race riots and church bombings.” According to Snyder, “it is not uncommon for textbooks to include even the most grisly of images, such as a photograph of the charred body of seventeen-year-old Jesse Washington, lynched in Waco, Texas, on May 15, 1916.”

Perhaps the fiercest debate is over whether to teach that the United States has overcome its dark legacy of racial discrimination, or whether, as The 1619 Project suggests, slavery’s harms continue to oppress Black Americans in the present. “White supremacy affects every element of the U.S. education system,” argues Learning for Justice, a national social justice nonprofit that provides free resources to educators and school districts, on the cover of its spring 2021 magazine. In a sponsored session at the National Council for the Social Studies conference—entitled “Teaching Honest History Through Critical Inquiry”—Learning for Justice facilitators asked participants, “How comfortable are you teaching about American enslavement, including the idea that it shaped the fundamental beliefs of Americans about race and whiteness?” They encouraged educators to avoid interpreting historical texts through a “white, Eurocentric” lens that would perpetuate stereotypes, and instead to teach students “resistant” readings, which in their definition lend themselves to anti-racist interpretation and challenge dominant cultural beliefs.

Part of what makes the fights over how to teach history and social studies so tricky is that, while virtually everyone says they oppose racism, enormous disagreement exists, within the broad left as well as between left and right, about what an anti-racist education should look like. Ibram X. Kendi, one of the most influential writers on anti-racism, argues against standardized tests, calling them “the most effective racist weapon ever devised to objectively degrade Black minds.” Others see testing as a key tool for leveling the playing field for marginalized students, allowing them to access opportunity and compete on merit, and they view moves away as discriminatory against Asians, who tend to perform better on the exams. Still others see the very ideas of competition and meritocracy as by-products of white supremacy. Tema Okun, a popular consultant on issues of diversity, equity, and inclusion, describes “a sense of urgency,” “perfectionism,” and “individualism” as values inherent to white supremacist culture. In Learning for Justice’s spring issue, an educator describing anti-racist teaching voiced a similar opinion: She sees white supremacy wherever there’s a “sense of urgency to meet particular deadlines that don’t necessarily speak to actual student growth.”

The Seattle parents who complained about Courageous Conversation, the curriculum Jonathan Greenberg was punished for incorporating, were not the last family to object to the ideas it encouraged. And even people who broadly agree with including discussions of racism in the classroom might object to certain arguments of Courageous Conversation’s founder, Glenn Singleton. One New York Times Magazine article, for instance, quoted Singleton as saying that valuing writing over other forms of communication is “a hallmark of whiteness” that harms Black students. (Brooke Gregory, the president of Courageous Conversation, argued that most critics of the program haven’t participated and misunderstand its goals. The point, she said, “is not to demonize anyone, it is not to create good and bad or right and wrong, it is to say that all of these voices have a need to be heard and understood.”)

Most parents organizing against critical race theory have been white, but not exclusively. Last spring, Shawntel Cooper, a Black mother of two, testified at a Loudoun County school board meeting that was picked up by national news, and has since spoken out in the media about teacher training materials she finds offensive, like one obtained via FOIA that contrasted “White Individualism” with “Color Group Collectivism.” Cooper said she did not identify with the values ascribed to the “Color Group” side, which didn’t include things like private property and independence. The trainings also asserted that “culturally competent professionals” do not embrace color blindness, and they “accept responsibility” for their own racism and sexism. “I don’t understand how you would not want to ban anything that is this divisive and divides each other because of color,” Cooper said.

When I asked Jalaya Liles Dunn, the director of Learning for Justice, how her group is contending with the possibility that educators will face political backlash if they incorporate their more radical resources, she said her members have been talking with teachers about how to develop materials that won’t get them in trouble. “We’re being really practical about what teachers can and can’t say, and can and can’t do,” she said. “We don’t create a finished product and say ‘This is what teachers need’.... They know what they need, they’re on the front lines.”

The claims of parents in Erickson’s Facebook group notwithstanding, the idea that concerned communities might be satisfied by teachers presenting multiple viewpoints on thorny subjects is not borne out by history. Even before the wave of anti–critical race theory bills, most public schools throughout our nation’s past have shied away from teaching controversial issues. In The Case for Contention (2017), co-authors Jonathan Zimmerman and Emily Robertson, a philosopher of education, note that, in general, communities have not wanted their schools to present “both sides” of an issue, much preferring teachers to reinforce local norms. Indeed, “the most significant restriction” on public school teachers tackling controversial issues, Zimmerman and Robertson conclude, has always been the public itself. Educators, who keenly feel this distrust, have generally chosen to stick to topics they believe will agitate no one.

The law offers K-12 teachers who do suffer backlash little protection. It’s been more than 50 years since the high point for teachers’ free speech. In 1967, the U.S. Supreme Court issued a landmark decision concluding that loyalty oaths, including anti-communist pledges, violated educators’ First Amendment rights. In 1968, the court ruled in favor of Marvin Pickering, a teacher who had written a letter to his local paper opposing a tax levy decision made by his school board and criticizing the board’s tendency to allocate funds to sports over academics. The board fired Pickering, but since his letter didn’t criticize the school employees with whom he worked on a daily basis and pertained to a matter of public concern, the court said his speech should be protected. And in 1969, the Supreme Court ruled in its famous Tinker v. Des Moines decision that neither students nor teachers “shed their constitutional rights to freedom of speech or expression at the schoolhouse gate.”

Since then, however, the courts have largely retreated from protecting teacher free speech at the K-12 level, both inside and outside the classroom. In 2006, for example, the Supreme Court ruled that when public employees speak in the context of their jobs, they’re “not speaking as citizens for First Amendment purposes,” and thus should not be insulated from employer discipline. Less than a year later, the Seventh Circuit upheld the firing of an Indiana schoolteacher who told her class that she had honked in response to a HONK FOR PEACE sign protesting the U.S. invasion of Iraq and she believed in peaceful solutions to conflict. “The school system does not ‘regulate’ teachers’ speech as much as it hires that speech,” the court ruled, asserting that she could not cover topics or advocate perspectives in class that depart from what the local school board approves.

There are nearly 14,000 K-12 public school districts across the United States, and almost all are governed by locally elected school boards. Turnout in these elections is notoriously low, often just 5 or 10 percent of eligible voters. Nonetheless, these representatives are legally empowered to set policy on virtually everything related to their schools, from budgets and bus schedules to curriculum and enrollment boundaries. The major limitation on their authority comes from state lawmakers, who can impose obligations on local districts to do with school vaccinations, standardized testing, or, of course, new rules curtailing discussions of race.

“The fact of the matter is we work with a captive audience,” said Steven Cullison, a high school economics teacher, in a National Council for the Social Studies presentation he led about free speech. “That is, the law requires students to come to school, and what’s more, we require the community to pay for it. That means that the community has a right to far greater say in what occurs in a public K-12 school than, say, in a college or in a private school.” Speaking this fall on a podcast, Alice O’Brien, the general counsel for the National Education Association, told educators that if they work in a state that passes a law against teaching that the United States is systemically racist, they must be particularly careful about how they craft curricula and answer student questions. “I wish I didn’t have to say that,” she said. “But the fact is we do have members who have gotten in trouble for appearing to promote a viewpoint in their classroom that is at odds with that prohibition.”

If educators cannot deny the stake lawmakers, parents, and other community members have in shaping school curriculum, political leaders certainly question parents’ interest at their peril, as Terry McAuliffe discovered this past fall in his failed Virginia gubernatorial bid. In a late September campaign debate, McAuliffe said a few words he would never live down. “I’m not going to let parents come into schools and actually take books out and make their own decisions,” he announced. “I don’t think parents should be telling schools what they should teach.” In the closing weeks of the race, Youngkin’s campaign made those remarks a centerpiece, running ads and circulating petitions proclaiming that “Parents Matter.” Post-election public opinion research showed that McAuliffe’s comments were highly influential, including among Biden voters who cast their ballots for Youngkin.

Though the fact often gets lost in contemporary media coverage, it’s never been only conservative parents who have disputed what’s taught in schools. Throughout the twentieth century, Black parents, with the assistance of the National Urban League and the NAACP, challenged school boards and book publishers about racist passages that they found in textbooks. The advent of ethnic studies courses, too, was driven by families pressuring their local leaders for more equitable representation in the classroom.

Perhaps surprisingly, not just parents think parents should have a say in curricula. In November, in a nationally representative EdWeek Research Center survey of district administrators and teachers, 63 percent of respondents said local parents should be involved in selecting the curriculum and materials, even though just 31 percent said parents are involved. And while it may be because they are so eager to avoid fights and criticism, more than 50 percent of educators said they supported letting parents opt their children out of classes, curricula, or units they disapprove of; 25 percent even said they “completely support” the idea.

In 2013, following the news that Greenberg would be transferred to another Seattle school, fellow teachers and former and current students rallied to his defense, shocked by how quickly administrators had caved to the grievances of a single family. More than 100 of his supporters showed up to a Seattle school board meeting decked out in green clothes, and at the school’s graduation ceremony that year, a senior delivered a speech demanding Greenberg’s reinstatement, after which his peers opened their gowns to reveal shirts with the letter “G” on chest plates. Although Greenberg was forced to spend the next year working at a middle school, an arbitrator eventually ruled that the school district had inappropriately used a transfer to punish him, and permitted him to return to his old job.

Greenberg, who still teaches high school civics in Seattle, has noticed changes in his two-plus decades in the classroom. “Students are so much more aware of systemic oppression than they used to be,” he remarked. When he used to ask his classes why people were poor, teens tended to invoke individual choice. “Now there’s a reluctancy to even mention individual choices,” he said. “I credit Black Lives Matter with so much of that. Back in the day, I might have just been happy to even discuss the concept of ‘white privilege’ with my class—now I feel like it’s not even a debate.”

Few teachers today, though, feel confident that they’d get their jobs back if they got on a parent’s bad side, and Greenberg himself suspects that his own race and gender played a role in the community’s defense of him. “I certainly feel like educators of color who get persecuted don’t get that showing of support,” he told me.

Keith Mayes, the University of Minnesota historian who helped Anoka-Hennepin social studies teachers include more Black history, sees community backlash to critical race theory as just a “foot in the door,” the first step in a project to eventually go after ethnic studies courses, racial equity initiatives, and broader discussions of racism. While he recognizes that the fear educators experience is real, Mayes thinks that what is most needed is backbone. “The real question will be how well-meaning white teachers and administrators stand up to this opposition,” he said. “That’s the fundamental question, and I’m always watching that.” Teachers, after all, are members of their communities, too; they can elect candidates for school board, testify at meetings, and advocate collectively for their interests.

In the end, as communities continue to spar, it will be students who pay the price for the laws, rules, and cultural pressures that deter educators from tackling so-called divisive subjects. A wealth of research, from both nationally representative samples of schools and individual schools, has shown that students who are encouraged to discuss controversial issues are more likely to develop civic tolerance, political interests, a sense of civic duty, and expectations of voting than their peers without similar classroom experiences. Teachers “cannot simply be mouthpieces for the state nor conduits for the majority beliefs in the local community,” Zimmerman and Robertson argue. But are we willing, on the left or the right, for teachers to be anything else?