In a sense, all of Emily Dickinson’s letters are “love-letters.” To her, little besides love, human and divine, was worth writing about, and often the two seemed to fuse. That abundance of detail—descriptions of daily life, clothes, food, travels, etc.—that is found in what are usually considered “good letters” plays very little part in hers. Instead, there is a constant insistence on the strength of her affections, an almost childish daring and repetitiveness about them that must sometimes have been very hard to take. Is it a tribute to her choice of friends, and to the friends themselves, that they could take it and frequently appreciate her as a poet’ as well? Or is it occasionally only a tribute to the bad taste and extreme sentimentality of the times?

At any rate, a letter containing such, to us at present, embarrassing remarks as, “I’d love to be a bird or a bee, that whether hum or sing, still might be near you,” is rescued in the nick of time by a sentence like, “If it wasn’t for broad daylight, and cooking-stoves, and roosters, I’m afraid you would have occasion to smile at my letters often, but so sure as ‘this mortal’ essays immortality, a crow from a neighboring farm-yard dissipates the illusion, and I am here again.”

In modern correspondence expressions of feeling have gone underground: but if we are sometimes embarrassed by Emily Dickinson’s letters we are spared the contemporary letter-writer’s cynicism and “humor.”

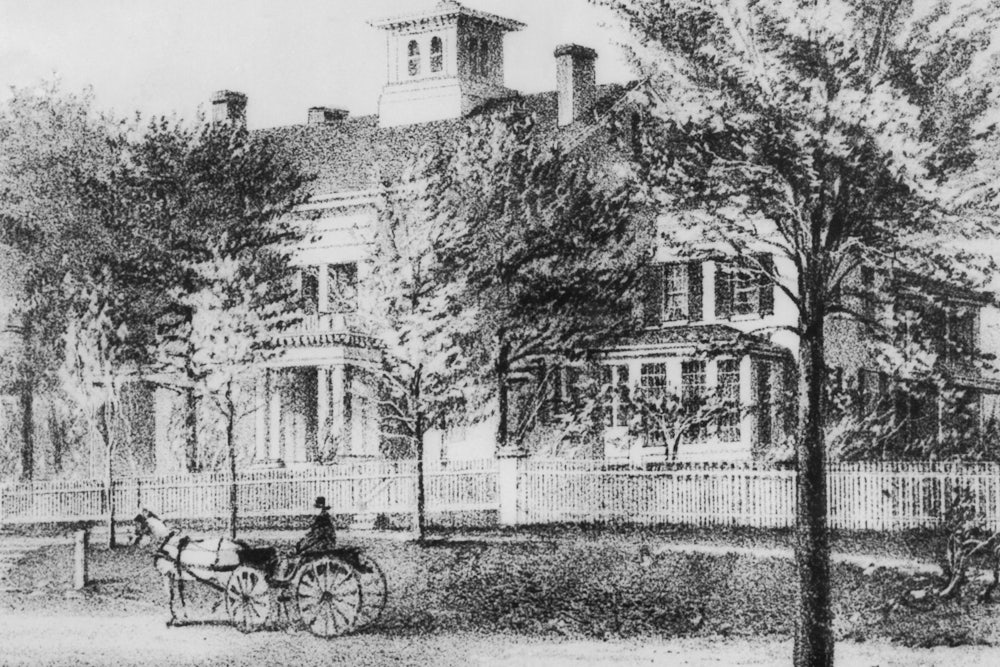

This beautifully edited collection of 93 letters written to Doctor and Mrs. Holland covers the last 33 years of Emily Dickinson’s life. Dr. Holland had begun his career as a rather reluctant country doctor, and he went on to become a wealthy citizen, a popular lecturer, the editor of the Springfield Republican, and finally the founder and editor of Scribners Monthly.

It is curious to think of the Dickinson family reading the Springfield Republican as religiously as they must have from the many glancing references to it; but except for generalizations usually turned into metaphors, current events rarely appear in these letters of gratitude and devotion. As in her poetry, Emily Dickinson is interested in Geography (in which “Heaven” seems to be one of the most familiar places) and the Seasons, and in her own combinations of both.

“It is also November. The moons are more laconic and the sun downs sterner, and Gibraltar lights make the village foreign. November always seemed to me the Norway of the year.” “February passed like a skate. . . . My flowers are near and foreign, and I have but to cross the floor to stand in the Spice Isles.” And in the concluding letters, when Mrs. Holland is visiting in Florida, Emily Dickinson speaks of it as if it were Heaven, with which she is familiar, as well as an earthly state of which she is very ignorant.

The use of homely images, and their solidity, remind one over and over of George Herbert, and as the letters grow more terse and epigrammatic, one is reminded not only of Herbert’s poetry but of whole sections of his “Outlandish Proverbs.” And one is grateful for the sketchiness: it is nice for a change to know a poet who never felt the need for apologies and essays, long paragraphs, or even for long sentences. Yet these letters have structure and strength. It is the sketchiness of the water-spider, tenaciously holding to its upstream position by means of the faintest ripples, while making one aware of the current of death and the darkness below.

The careful study of Emily Dickinson’s changing handwriting, appended to this volume, bears out this image pictorially. Among other illustrations there is a charming photograph of Lavinia Dickinson, laughing, and holding one of her innumerable cats that seem to have been a trial to her adored sister. Twenty-nine of the letters are included in the most recent edition of Letters of Emily Dickinson, edited by Mabel Loomis Todd, with an introduction by Mark Van Doren. Mrs. Holland died believing that all the others had been lost, but some sixty more have now been found and further ones may yet come to light.