A newly drawn congressional map in New York is roiling Democratic politics in the state and nationwide, as lawmakers have been suddenly pitted against each other in districts that some argue disenfranchise certain voters. The map has far-reaching implications for Democrats’ already Sisyphean task of maintaining control of the U.S. House of Representatives, as it will likely wipe out potential Democratic gains that were balanced against redistricting moves benefiting Republicans in other states.

Campaigns in New York were thrown into chaos last month, when the state Court of Appeals ruled that Democratic lawmakers had violated the state Constitution by drawing new congressional and state Senate districts that disproportionately benefited Democrats. Voters adopted an amendment to the state Constitution in 2014 to limit partisanship in the redistricting process. However, the independent redistricting commission compelled by the amendment broke down amid partisan spats earlier this year, allowing the Democratic supermajorities in both chambers to push through a map gerrymandered in favor of their party. So where Republican efforts to gerrymander districts in their favor have largely succeeded in red states, the Democratic attempt to play hardball in New York just resulted in the ball flying back and smacking them in the face.

“Democrats probably did overreach. But in this environment, you’re either matching your opponent’s maximalist approach here, or you’re essentially unilaterally disarming,” a Democratic strategist based in New York told The New Republic, speaking on the condition of anonymity to discuss the situation candidly. “So in this case, Democrats went for a maximalist approach … and they’re now getting a haircut.”

The previous map drawn by Democrats had given them several pickup opportunities, even as the state lost one congressional district overall because of relatively stagnant population growth. (However, new data shows that census takers miscounted certain state populations, including in New York.) The new map drawn by a court-appointed special master—yes, that is the actual title—erased those gains. The lines drafted by Jonathan Cervas, a postdoctoral fellow at Carnegie Mellon University who previously consulted on Pennsylvania’s redistricting process, left New Yorkers reeling.

“This was the most calamitous and least predictable outcome for New York. Nobody thought we’d go from an initial map where we’d pick up as many as six seats to a map where we lose as many as two, and maybe more,” said Steve Israel, a former representative from New York. Israel chaired the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee during the previous round of redistricting ahead of the 2012 midterm elections.

A draft of the new map was released on May 16, with stakeholders having the opportunity to submit feedback throughout the week before a final map was produced on Friday. The newly drawn map features districts that are more compact, particularly in New York City, which is famed for its unusually apportioned seats. But opponents of the special master’s draft map argued that the odd shapes of many current districts reflect the historic racial and ethnic makeup of those areas, thus giving those populations a voice in Congress.

“It certainly is a fairer map from the partisan perspective than the one passed by the legislature,” Michael Li, senior counsel for the Democracy Program at the Brennan Center, told The New Republic on Friday. “The bigger issue is whether the map gets the right balance with respect to various communities, and in particular, communities of color. It’s unclear to me that the map violates the Voting Rights Act, which is not to say it doesn’t necessarily adversely affect communities of color.”

Cervas seems to have taken some of these considerations into account in the finalized map, reuniting some communities that he had divided. One such example was Sunset Park, a neighborhood in Brooklyn that was previously divided between the districts of Representative Jerry Nadler and Representative Nydia Velazquez. Sunset Park has significant Asian and Hispanic populations, Lerner argued, so it made sense for part of the neighborhood to belong to Nadler’s district, which includes Chinatown in Manhattan, and part to Velazquez’s district, which has a plurality Hispanic population. But under the special master’s initial map, the entirety of Sunset Park had been drawn into a new district with Staten Island, with smaller Hispanic and Asian populations. Cervas’s initial map therefore “significantly diminished their voice within the district,” said Susan Lerner, the executive director of Common Cause New York, an advocacy group that opposed the new map.

“The current maps are often pointed to, ‘Oh, look how terrible they are.’ But they are drafted to give specific communities a fair chance to choose their own representatives,” Lerner said. She noted that a special master appointed by a federal court had drawn the previous congressional map and said that he had taken these demographic factors into account.

In the finalized map, Cervas reunited Sunset Park with Chinatown in lower Manhattan in the new 10th congressional district.

The new map will also result in multiple head-to-head matchups between current members of Congress, infuriating Democrats statewide and nationally. This includes a battle between Nadler and Representative Carolyn Maloney, who currently represent different parts of Manhattan but now will be forced to run against each other. Nadler and Maloney are both seasoned politicians who have served in Congress for more than two decades, and each chair influential committees—Nadler the Judiciary Committee and Maloney the Oversight and Reform Committee. The finalized map would still merge those two seats, setting up a battle between the two longtime representatives.

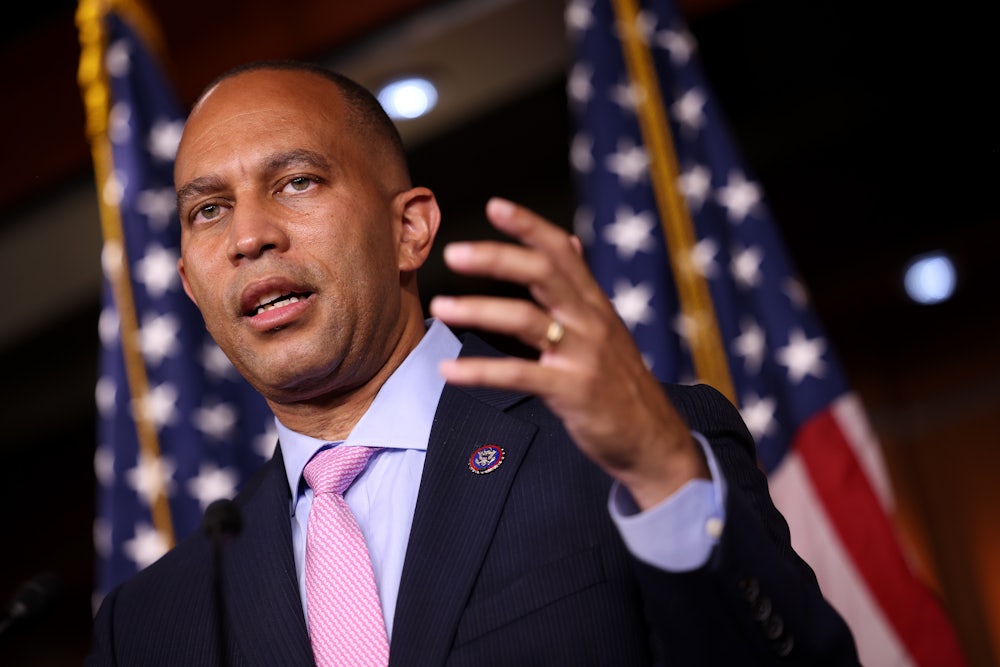

Representative Hakeem Jeffries, the chair of the House Democratic Caucus, has argued that the changes in the new map particularly disenfranchise Black voters. Jeffries has been thrown into the same district as Representative Yvette Clarke, another Black lawmaker. In an interview with The New York Times on Thursday, Jeffries called his fight against the new map “an all-hands-on-deck moment.”

A recent digital ad from Jeffries argues that the changes took “a sledgehammer to Black districts” and are “enough to make Jim Crow blush.” These included splitting up historically Black communities of Bedford-Stuyvesant in Brooklyn and Co-Op City in the Bronx into multiple districts, which opponents of the map argue dilutes the voices of Black voters. (Jeffries did not submit any comments formally for consideration by the special master; he sent a letter earlier in May to the judge who appointed Cervas asking for additional hearings for stakeholders to consult on the process, arguing that “thousands of my constituents, communities of color and millions of other New Yorkers are being denied a meaningful opportunity to present their views as it relates to legislative representation in Albany and in Congress.”) Cervas took these community complaints into consideration, reuniting Bedford-Stuyvesant and Crown Heights, another historically Black community in Brooklyn, into single districts. Responding to criticism about the initial map, Cervas said that the communities had been “inadvertently split.”

The special master received hundreds of comments making special appeals to change the district lines from Democrats opposed to the map, Republicans who think it could go further, and ordinary citizens. One letter outlined the cultural distinctions among Jewish communities in Manhattan, arguing that they should not be lumped together in one district as the new map suggests; this complaint did not end up changing Cervas’s mind. A letter submitted by Common Cause New York argued that Cervas had focused on compactness of districts at the expense of preserving the rights of historically marginalized communities. Other letters submitted by attorneys for the Democratic majorities in the state legislature argued that the map violated state law by unfairly disadvantaging incumbents.

“People do not live, work, and play in neat lines and boxes. So if you’re actually going to reflect the lived reality of communities, your lines are not going to be as pretty, but they will be realistic,” Lerner told The New Republic.

But Li noted that the language in the state Constitution was ambiguous. The Constitution calls on a commission tasked with drawing district lines to “consider whether such lines would result in the denial or abridgment of racial or language minority voting rights” and “consider the maintenance of cores of existing districts.” But the degree to which such considerations should be taken into account—and indeed, what it even means to consider—is left unsaid.

“The New York Constitution is not the most sharply drafted or formed. I think that makes it hard, especially for a map-drawer that is coming in brand new to this process and given very little time,” Li said. “It’s sort of like coming into a kitchen that you’ve never worked in and [being] given a recipe where the instructions aren’t very clear and you’re supposed to produce a meal in 20 minutes.”

In a five-page order approving the final congressional and state Senate maps, Justice Patrick McAllister of the Supreme Court of Steuben County—who had appointed Cervas—rebutted many of the criticisms leveled against the special master. While McAllister, a Republican, acknowledged “the time frame for developing new maps was less than ideal,” he said Cervas and his team were to be “commended” for drafting the maps in such a short period.

“Unfortunately some people have encouraged the public to believe that now the court gets to create its own gerrymandered maps that favor Republicans. Such could not be further than the truth. The court is not politically biased,” McAllister said.

Opponents of the map also said that the problems are not only concentrated in New York City. Under the new map, Representatives Jamaal Bowman and Mondaire Jones, both Black freshman lawmakers, would reside in the same district. (Members of Congress do not need to live in the district they represent.) But Jones currently represents the vast majority of the population of the new 17th congressional district. Just moments after the new draft map was revealed last Monday, Representative Sean Patrick Maloney—the chair of the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee—announced that he would not be running in the district where most of his current constituents reside but would instead run in the 17th congressional district.

Maloney’s decision infuriated many other Democrats, who accused him of prioritizing running for a safer seat rather than trying to maintain control of the district where most of his constituents reside, and attempting to muscle out Black lawmakers in doing so. (The newly drawn 18th congressional district would have supported President Joe Biden by a single-digit margin in 2020.) Jones told Politico that Maloney did not inform him before announcing that he would run in the 17th congressional district, which “tells you everything you need to know about Sean Patrick Maloney.” In a tweet last week, Representative Ritchie Torres, a Black lawmaker who currently represents a district in the Bronx, cited reporting by Punchbowl News that Maloney allies believed Jones would be ideologically suited to another district.

“The thinly veiled racism here is profoundly disappointing. A black man is ideologically ill suited to represent a Westchester County District that he represents presently and won decisively in 2020? Outrageous,” Torres tweeted, arguing that the solution was for Maloney to run in the 18th congressional district, which he primarily represents.

But despite incurring the ire of some of his fellow Democrats in New York, Maloney has the support of one key Democrat: Speaker Nancy Pelosi. “I’m not getting involved in the politics of New York and the redistricting. He, as well as other Members of the New York delegation, said they were going to run in districts where their home is,” Pelosi said during her weekly press conference last Thursday. She reiterated that the caucus leadership was “very proud” of Maloney.

Israel told The New Republic that he did not find Maloney’s calculation surprising. “The thing that’s truly bipartisan about Washington politics is survival. I don’t care if you’re Democrat or Republican, you want to survive at the end of the day. So he’s doing what he has to do to survive politically,” Israel said.

The drama appeared to be smoothed over by Friday, when Jones announced that he would run in the 10th congressional district, encompassing lower Manhattan and Brooklyn—a significant distance from his current Westchester-based district. “This is the birthplace of the LGBTQ+ rights movement. Since long before the Stonewall Uprising, queer people of color have sought refuge within its borders,” Jones, who is gay, wrote on Twitter. “I’m excited to make my case for why I’m the right person to lead this district forward and to continue my work in Congress to save our democracy from the threats of the far right.”

But Jones won’t be the only high-profile candidate running in that district. Former New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio announced on Friday that he would run in the newly drawn 10th congressional district, even before the map was finalized. Despite his deep unpopularity as mayor and his disastrous run for president, de Blasio would have the edge of name recognition. (Velazquez, who lives within the new district lines, previously said she would run in the 7th congressional district.)

Lest readers complain that this article is too focused on downstate concerns: The initial map had Saratoga Springs, which is typically considered part of the Capital Region near Albany, lumped into a district with the Adirondacks farther north. This development angered more than one resident of Saratoga Springs and its surrounding towns. The final map reunited Saratoga Springs with Albany.

Cervas also significantly reoriented his maps of Long Island, dividing districts on the island by north and south instead of east and west. This resulted in reuniting some towns with historically marginalized communities, like Hempstead in Nassau County. But the finalized map still keeps the districts in Suffolk County farther to the east of Long Island highly competitive.

In western New York, the finalized map largely reunited Buffalo and the Niagara area. Two Republicans avoided potential head-to-head matchups, as Representative Claudia Tenney announced she would run in the newly drawn 24th congressional district, and Representative Chris Jacobs said he would run in the 23rd congressional district.

As candidates and incumbents scramble to campaign in their new districts ahead of the August 23 primary, the map will still likely face legal challenges, meaning that even more changes are still possible. But the clock is ticking: Cervas was only given a few weeks to draw the map in large part because of the tight timeline in needing to have all the resources prepared and ballots printed by the time early voting begins in July. Li noted that New York was in unfamiliar territory with legal fights over redistricting.

“This is New York’s first rodeo. These judges are not experts on the election process, and I think they created a situation where they really wanted the map to be redrawn, but that also meant working under really next to impossible circumstances,” Li said. But this short time frame is due to the blatant partisanship of the initial map, he said: “A train wreck of Democrats’ own creation.”

The new map in New York, and the various battles it sets up, will have far-reaching effects for Democrats nationally. It will affect the Congressional Black Caucus, which will likely see its ranks thin somewhat with the potential loss of some Black Democrats in New York. And in the immediate term, it distracts Democrats from the already Herculean task of keeping the House. “It’s not constructive or helpful for Democrats to be fighting with each other at a moment where they’re dealing with incredibly difficult terrain as it is,” the Democratic strategist said.

When asked how he would have reacted as DCCC chair when the special master’s map was released, Israel laughed. “My first reaction would have been to remove all sharp knives from the building from the DCCC headquarters,” he said.

* This article has been updated.