Imagine growing up in the 1980s as the child of Indian immigrants in Canada, the United Kingdom, or the United States. Imagine trying to find a model, someone who mattered to the larger culture around you, and failing. None of the people who move others with their words, deeds, or songs seem to have your story, your burdens, or your sense of the world. You have not yet heard the word “cosmopolitan,” but you do have a sense of living in the world yet displaced from any particular part of it. No one else’s kitchen smells like yours. No one else’s parents fight like yours. No one else has grandparents who don’t speak English but watch English television for hours anyway. Where do you find inspiration, or even just comfort, that there is a way you might matter in this cruel yet dynamic culture?

Then one day in 1978 you see Freddie Mercury on The Midnight Special television program singing “We are the Champions.” He’s tan like you. He’s loud. He’s sexual. He does not care about anyone who can’t handle his presence or his performance. A bit of reading reveals Mercury, too, is a desi—a “person of the country,” of South Asian descent. He, too, had traditional parents but heard the thumping, erotic call of rock and roll and knew he could never be like them. You suspected, but would not know for some years, that there was even more to his journey than just a rebellion against desi traditions. But for now, he was something else. And damn, you needed that.

As you grow you wonder why there are no other desi politicians, actors, sports stars, or writers who seem to matter. You catch glimpses of tennis player Vijay Amritraj losing to Björn Borg at Wimbledon (like everyone else did) in 1979. But that image has no staying power for you. Losing is losing.

Then, in 1981, you begin to read about a new writer. He’s young and brash. He wins a big literary prize for his new novel, one that purports to tell the story of the Independence and ultimate partition of India, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, and Bangladesh. The novel itself proves to be difficult going for you, so far underexposed to big, ambitious works of fiction. But you take an interest because here is a guy who does not stand down, does not bow to the Sahibs. And the Sahibs seem to reward him for it.

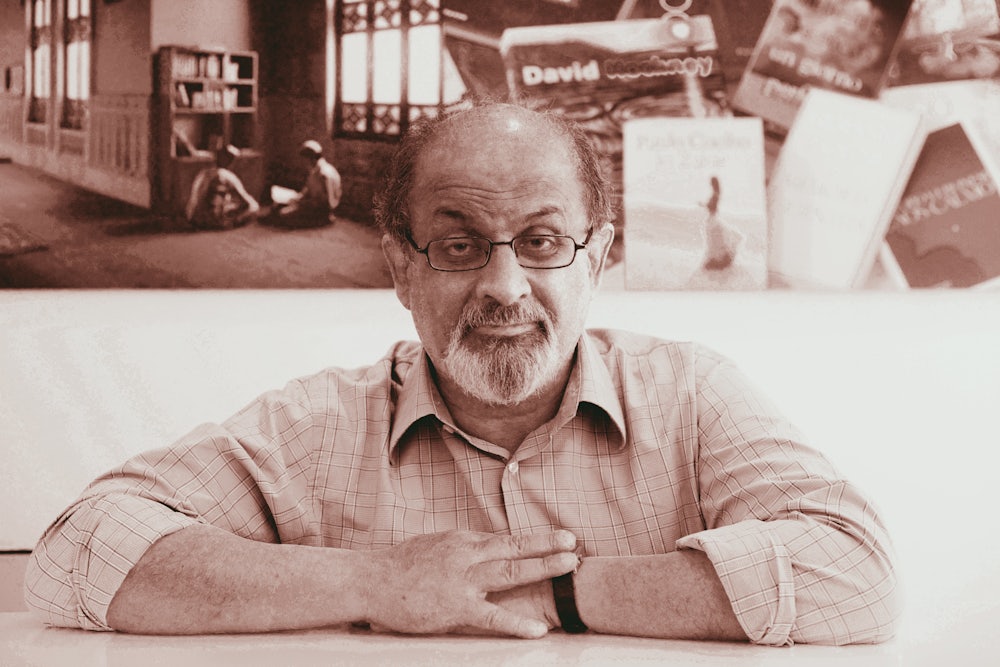

Now, as Salman Rushdie lies in a hospital bed in northern Pennsylvania, recovering from stab wounds inflicted after he spoke publicly about his life and work, writers and desis across the world are reflecting on what Rushdie has meant to them. You are among them.

Midnight’s Children, Rushdie’s second novel, sat among Carl Sagan’s Cosmos and John Irving’s The Hotel New Hampshire on the coffee tables of all the white people you knew who fashioned themselves bookish in the early 1980s. Suddenly, everyone seemed to care about India, or at least about one British Indian. Inspired again, and a bit embarrassed that you, the Indian kid, can’t talk about it, you forge about three chapters into the book. There you see a brief account of the 1919 massacre of hundreds of Indians protesting in Amritsar, Punjab. “‘Good shooting,’ Dyer [the British commander] tells his men, ‘We have done a jolly good thing,’” Rushdie writes with economy and power.

It leaves you shaking. It’s not that you did not imagine such brutality coming from the British. It’s that no one had ever told you that story, and it seems rather important. Indian independence was not the happy, nonviolent story that you had heard your whole life—one of a reasonable, enlightened democracy relinquishing its gentle control over an aspiring democracy when the time was right—but a horrifying process that revealed just how mercenary a colonial power could be.

A year later, in 1982, Richard Attenborough showed the Amritsar massacre in Gandhi, which went on to win Best Picture at the Academy Awards. A desi, Ben Kingsley, won an Oscar for Best Actor in the film. You appreciated Gandhi, but it made you uneasy as well. Why did it take a white English director to bring that story to the world? Why did he have to deploy white sidekicks to Gandhi, played by esteemed American actors like Candace Bergen and Martin Sheen? “Rushdie already told this story, and he did it with all the complexity and strangeness that it deserves,” you want to say.

Meanwhile, the world is roiling and you are growing in voice and ambition. You discover a few more desi voices out there. Anita Desai wins some prizes. Bharati Mukherjee sells many books and generates some good reviews for her work. Yet it was Rushdie who generated most attention. As his fame rose through the 1980s, Rushdie was unparalleled in calling out the British empire and its remains for their persistent racism. British postcolonialism was hardly more civil or moral than its colonialism, laced with white resentment. Some others captured the cruelty of that domestic resentment, as Hanif Kureishi did in his brilliant screenplay for Stephen Frears’s 1985 film My Beautiful Laundrette. But again, a white, English director told the story in his way, and the film boosted the career of Daniel Day-Lewis rather than of Gordon Warnecke, who played Omar, the desi at the center of the story.

“Our story does not begin or end with Gandhi,” you want to shout, as you read more and live more and deal with all the impositions of exoticism and exile. And you start to wonder if there is an “our” story at all.

After all, India and Pakistan had been at almost constant war since partition. Sri Lanka was starting what would be a 30-year civil war between Tamils, who are largely Hindu, and the majority Sinhalese, who are mostly Buddhist. And India itself, with its official secularism and three-colored flag (including saffron for Hindus and green for Muslims), was showing its fraying seams.

In 1984, Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, one of Rushdie’s great nemeses because of her authoritarian nature and actions, ordered troops to invade the sacred Sikh golden temple in Amritsar. Sikh separatists had occupied the temple. The Indian military attack killed 83 people and enraged Sikh communities in India, Pakistan, and across the diaspora. Friends in Toronto and Liverpool turned on friends, just as they were doing in Delhi and Bombay (now Mumbai). Five months later, two of Gandhi’s Sikh bodyguards assassinated her, sparking Hindu-led riots across India.

So who were “we?” Could those of us who were Hindu claim common cause with our Muslim or Sikh or even Christian friends who shopped at the same stores and watched the same poorly dubbed Indian films on tape? Over this time bonds between families across caste, religion, and ethnicity frayed. Communities grew, so it was possible to keep to one’s own kind and elide desi solidarity as a coping mechanism for living as part of a vulnerable minority. Little did you know it would all get much worse.

The portable versions of Islam, Hinduism, Sikhism, Jainism, and Theravada Buddhism as practiced by the sparse communities in North America and Europe in the 1970s were ecumenical. They made many compromises and curbed their more extreme and intolerant expressions. Intolerance is a luxury that flows from security and insularity, after all.

Then came The Satanic Verses. Rushdie was already held in contempt by fundamentalist Hindus, mostly because he is Muslim, but also because he dared to tell the story of India and Indians as if Muslims could, as if they were true citizens of Bharat (a Sanskrit word that often stands in for an imagined, ancient, pre-Muslim India). Now, Muslim extremists came after Rushdie with a violent fervor that far surpassed any anger or dismissal Rushdie’s Hindu critics had been able to muster.

Published in 1988, The Satanic Verses was Rushdie’s fourth novel and it quickly surpassed Midnight’s Children in notoriety. It remains his most stylistically and politically ambitious work. It relates through fractured narratives the experience of being unmoored from a place of origin, cautiously accepted and rudely rejected by a destination of migration, and the dizziness of living with a cosmopolitan sensibility in a world that demands one declare one’s roots. To read The Satanic Verses is to feel, almost experience, what so many of us live every day. To the rooted, the traditional, this work might even provide a cautionary tale: Perhaps one should nurture one’s roots after all. But that’s not how the most outraged saw it, mostly because so few actually read it.

To a true believer there is no sin greater than apostasy. That Rushdie was raised a Muslim, albeit a secular, alcohol-loving Muslim who soon would declare his atheism, made his descriptions of the Prophet even more troubling than if some outsider had ignorantly portrayed the same. Pakistan banned The Satanic Verses just weeks after its publication. Three months later thousands of people protested the book outside the American Cultural Center in Islamabad, Pakistan. India quickly tried to head off similar protests by banning the importation of the book.

Then, it got personal. Iran’s supreme leader, the Ayatollah Khomeini, ordered his followers to kill Rushdie. The threat was credible enough that Rushdie asked for and received protection from Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher’s government—a government that Rushdie had mercilessly criticized for years. A few Labour politicians complained because they opposed the book; a few Conservative leaders opposed the protection because they considered Rushdie to be morally unworthy and hypocritical. It did not help that Rushdie is Asian (as they say more frequently than “desi” in the United Kingdom).

Four of Rushdie’s translators around the world were attacked. Two were seriously injured. A Japanese translator, Hitoshi Igarashi, died from stab wounds in 1991. This was not a bloodless or idle threat. Rushdie remained under protection and largely in hiding from 1989 through 2001. Since then he has made New York City his home and has appeared in public regularly, despite the persistent threats to his life.

You always took inspiration from Rushdie’s courage in the face of calls for his death. As you saw religious boundaries thicken and bigoted rhetoric coarsen over your life, you understood that many would die because of perceived umbrage. That’s just what happened in India, Pakistan, Myanmar, and Sri Lanka over the past few decades. Any hope of the major religions of South Asia bending toward each other, allowing mutual love and respect to flow, seems like a mirage that evaporated when a Hindu fundamentalist killed Gandhi in 1948. Today, followers of that same extreme movement that killed Gandhi run India.

These days young desi readers looking for models can choose from dozens of talented writers in English like Kiran Desai, Arundhati Roy, Vikram Seth, Jhumpa Lahiri, Arvind Adiga, Amitav Ghosh, Anand Giridharadas, Atul Gawande, and Amitava Kumar. The novelist and playwright Ayad Akhtar now runs PEN America, an organization committed to protecting the rights and privileges of authors to express themselves freely and without fear.

Desi prominence and influence in Europe and North America are no longer rare. Gurinder Chadha directed Bend it Like Beckham and Born to Run, showing the tensions and possibilities that desi youth experience growing up in England. Actor Mindy Kaling inspires desi girls to be bold, funny, and themselves. Padma Lakshmi teaches us how to cook and eat better. Two U.S. states have elected desi governors this century. The next prime minister of the United Kingdom could be a desi. Leo Varadkar was Taoiseach of Ireland from 2017 to 2020. And the vice president of the United States, Kamala Harris, boasts of her roots in Chennai.

It’s not that none of this would have happened had Rushdie not written, not written so well, or not been threatened and attacked by religious zealots. It’s that Rushdie helped change how the majority cultures in Europe and North America saw desis. He defied stereotypes and resisted all assumptions. He became, through no choice of his own, something of a hero for free expression and courage in the face of oppression. That role opened up possibilities, imaginations, for desis who would eventually matter in the parts of the world in which they otherwise are exiled.

The original desi cosmopolitan, Rabindranath Tagore, warned of the corrosive threats of sectarianism and collective violence. He was also the first desi to win the Nobel Prize in literature. He did so in 1913, eight decades before India would ban the importation of The Satanic Verses. Those of us who live and thrive in the diaspora could still learn a lot from Tagore and Rushdie: Their vision of a freer, more secure sense of desi identity, unrestrained by colonialism, strong in the face of persistent racism, and above the fray of sectarian cant, should inspire us more as Rushdie recovers from his wounds. We can only hope he can write again soon.