In February 2015, Donald Trump complained that the media was not taking his bid for the Republican nomination seriously enough. “Everybody feels I’m doing this just to have fun or because it’s good for the brand,” he told The Washington Post.

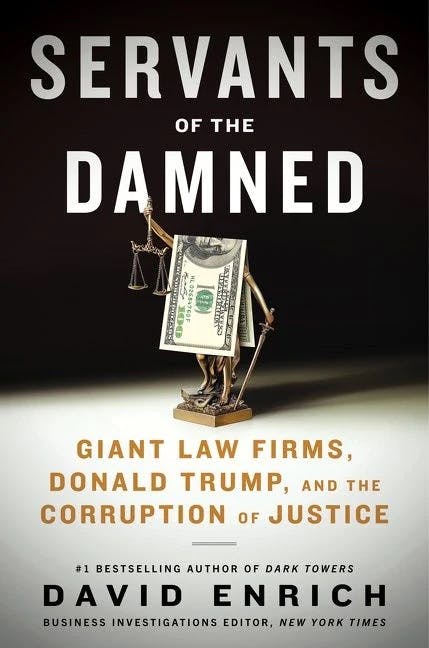

All that began to change when he hired Don McGahn, a lawyer from the firm Jones Day, to represent his campaign later that year. In Servants of the Damned: Giant Law Firms, Donald Trump, and the Corruption of Justice, business investigations editor at The New York Times David Enrich argues that Jones Day brought the Trump campaign the credibility and expertise it needed for victory in 2016. After the election, lawyers from the firm filled the ranks of the administration. From inside and outside the Trump White House, they worked on remaking the federal judiciary, and in the lead-up to the 2020 election, the firm threw its weight behind attempts to restrict mail-in voting.

I spoke over Zoom with Enrich about the firm’s rise, and its work on behalf of controversial clients, from Big Tobacco to Trump. We discussed the tactics the firm has used historically, how far lawyers should go to defend a client, and what responsibility Jones Day bears for the legacy of the Trump administration. Our conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Jack McCordick: So much of the book focuses on the ways that Jones Day lawyers enabled Trump and his administration’s excesses. What were they doing?

David Enrich: It started off actually before he was even elected president. By early 2016, Jones Day was helping Trump draw up lists of potential judicial nominees if he were to be elected president. That was not simply advance work in case he got elected. That was to send a signal to the Republican establishment that this was a man who could be trusted to represent conservative voters.

By the time he won the election in 2016, the entire law firm of Jones Day was basically working on the transition into the administration. They were helping to vet judicial nominees and people for senior posts in the White House, the Justice Department, and elsewhere in the administration.

And to a really extraordinary, unprecedented extent, they sent many lawyers from the firm to go work in the Trump administration. The White House counsel’s office was run by Don McGahn. He surrounded himself by and large with lawyers from Jones Day. The upper echelons of the Justice Department were at various points dominated by Jones Day—including the Solicitor General Neal Francisco [who left the firm to take that post and rejoined three years later]—but also people who were a rung or two below that who exerted enormous influence.

JM: What stands out to you as some of the more disturbing work they carried out?

DE: In the summer of 2020, as Trump’s rhetoric about the risks of fraud and a stolen election intensified, a lot of people within Jones Day started getting very nervous. A couple people actually resigned in anticipation of this. There was a debate inside the firm about whether they should drop the Trump campaign as a client and whether they should make some sort of clear public signal that there is a line that they would not cross. They didn’t do either of those things.

They kept working behind the scenes trying to help his campaign and went so far as to get involved in litigation in Pennsylvania on behalf of both the Republican Party and the Trump campaign in the weeks before the election. The effect of their involvement if they’d actually won in court—which they did not—was going to be to make it much harder for absentee and mail-in ballots to be counted. And the arguments they were peddling in this and related litigation boiled down to: There is a risk of fraud and there is a risk of the results being tainted by fraud if we cannot further restrict the use of mail-in ballots during a pandemic.

What Jones Day was doing in Pennsylvania was attempting to slow the vote counting and make it harder for certain absentee and mail-in ballots to count. A lot of the rhetoric that the firm’s lawyers were using in court filings legitimized and provided legal cover for some of the rhetoric that Trump and his allies had been using.

JM: In addition to investigating Jones Day’s work in right-wing politics, you spend much of the book charting the firm’s work on behalf of Big Tobacco. How did tobacco work shape the company’s culture?

DE: Jones Day started representing RJR [the R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company] in the mid-1980s, and it quickly became their single most important client. At one point, nearly 20 percent of the firm’s annual revenue was coming from this one Big Tobacco client.

To me, this was the beginning of an era when Jones Day started really going above and beyond what I think most people would regard as normal lawyering. I had always thought of a lawyer’s main job as showing up in court to fight lawsuits and maybe to advise behind the scenes on big corporate transactions. But at this point, starting in the mid to late ’80s, Jones Day really started taking it to a whole new level. A number of Jones Day lawyers essentially became paid public spokesmen for the tobacco industry. I came across in my research interviews that they’d given to PBS and other TV channels where they’re spreading what, at least now with the benefit of hindsight, seems like lies. They would dispute that they were lying at the time. But they were certainly trying to spread as much doubt as possible on what even at that point was pretty well-established science that nicotine was addictive and that smoking cigarettes was bad for you.

That was in the 1980s. By the 2000s, Jones Day and some of its very top lawyers were going around and threatening state and local governments that dared to impose regulations on various types of tobacco. And they were using all sorts of what I think could be classified as at best borderline legal tactics to try to make it as painful as possible for witnesses or plaintiffs to go up against tobacco companies.

JM: What kinds of tactics did they use?

DE: There’s an anecdote I mention in the book where the widow of a smoker who allegedly died from smoking-related illnesses is being deposed by Jones Day, and Jones Day lawyers took an opportunity in the deposition to break the news to the grieving widow that her husband had been having an extramarital affair. Jones Day’s argument in that case was that there was some tangential medical relevance, but this is a pattern of big corporate law firms, including Jones Day, unearthing very unflattering personal information and using it in a way that, intentionally or not, results in witnesses and plaintiffs really having second thoughts about whether to go forward. The widow in that case dropped her litigation because she was so worried about it becoming public.

JM: How do firms tend to justify taking these kinds of cases—working on behalf of Big Tobacco or a candidate like Trump?

DE: One of the things I wrestled with a bit was the question of where you draw the line as a lawyer or a law firm between the zealous representation of a client in legal jeopardy and behavior that is really not OK.

Everyone would agree that everyone, even companies, are entitled to a robust criminal defense. I think a lot of people would argue that everyone, including companies, is entitled to robust civil representation. But is it OK for law firms to be working to water down regulations or help companies avoid taxes or to intimidate potential witnesses?

I would argue that’s much more debatable than some of the more routine legal work that law firms provide, and yet I think the legal industry overall has often used this notion that everyone is entitled to competent legal counsel to justify a much wider range of at times controversial and troubling work than would fit under the most expansive definition of what lawyers are ethically or professionally obligated to provide.

JM: Are there other examples of work Jones Day has done that you think arguably crosses that line?

DE: Jones Day has long represented Abbott Laboratories, which is the health care company that, among other things, makes powdered infant formula. Abbott has faced a lot of lawsuits from families over the years whose babies have been brain-damaged after consuming formula.

In one particular case that I focus on in the book, the federal judge presiding over the case said it’s the worst conduct by a factor of 10 that he’s ever seen in his decades on the bench. Jones Day’s actions included coaching witnesses and abusive deposition practices. In another case on behalf of Abbott, Abbott tried to settle the case before trial and, when the plaintiff turned it down because it was too small a settlement, Abbott then tried to introduce into court some highly personal and damaging information that had just about zero to do with the case at hand in what the plaintiff and the plaintiff’s lawyer viewed as a clear attempt to intimidate and smear the plaintiff.

The list goes on, but to me the list culminates with the representation of Trump because that is something that clearly does not fit under the rubric of everyone being entitled to a robust defense. Jones Day went out and created a political law practice with the purpose of soliciting business from Republican politicians, then got into bed with Donald Trump not because Trump needed protection against powerful interests who were trying to sue him or charge him with crimes but because they sensed the political opportunity to make their mark. All of the work that flows from that, to me, is relevant because it shows that this is not traditional lawyerly work that is easily defendable on the grounds that everyone is entitled to competent legal counsel.

JM: Summing up Jones Day’s role in the aftermath of the 2020 election, you write that the firm “wasn’t responsible for January 6th, but it wasn’t not responsible.” How much blame should be placed on Jones Day for Trump’s legacy?

DE: It’s a tough question. I labored over that line in the book because Jones Day was not representing Trump or his campaign or the Republican Party in any of the frivolous and reckless lawsuits that were filed after the election that were just spreading lies about fraud and things like that.

That said, I think to really understand the role that Jones Day played, you have to go back to what happened in early 2015. In making the decision to take on Trump as a client, Jones Day imbued his fledgling campaign with an enormous amount of credibility. Would Trump have been elected in 2016 without Jones Day? Maybe. But it would’ve been a much harder slog. Jones Day professionalized his campaign. It helped him cement his ties to the conservative establishment. And once in office, it helped him professionalize his administration and presided over what is probably the single greatest legacy of the Trump administration, which is the remaking of the federal judiciary.

So, no, they’re not responsible for January 6 at all. But if Jones Day had never entered the scene and gotten into bed with Trump in the first place, would January 6 have happened? I think that’s a harder question. I think that everyone that was helping Trump get elected and remain president and giving legitimacy to his administration probably bears some amount of responsibility for the events that transpired when he refused to leave.