As the poet has it, we are born strangers and afraid in a world we never made and, he might have added, spend a large part of our lives negotiating that original aloneness. Most of us make some headway with the struggle, but some of us get nowhere with it; we remain people who are at home nowhere, with no one, feeling like strangers to ourselves and others all our lives. For such unfortunates, the aloneness is more than a penalty, it is a humiliation; humiliation is degrading; degradation induces fear and rage; fear and rage are doubly isolating. Such a destiny was the one meted out to the richly febrile writer Jean Rhys, whose gift for language and form made her stories and novels a compelling embodiment of the permanently forlorn.

She had known from the time she was young that men and women, especially men, fear their own sensuality; that this fear cuts deep, slicing through mind, spirit, and conventional decency. Very early, the glory and the murderousness of sexual relations became central to life as she would ever know it. If a woman was passionate, she reasoned, and aroused passion in a man, he hated her—hated and punished her. In fact, left her, as Rhys put it, “all smashed up.” To this insight she remained vulnerable all her life. Vulnerable but inspired. Seeing herself as an innocent repeatedly crushed by men of power who were aroused by her became the essentially autobiographical metaphor that dominated her work. Inevitably, Rhys’s fictional counterparts lead the reader to believe that they themselves are acting in good faith when it comes to sexual love; it is the men who uniformly use and betray them. So what can a Rhys woman do but drink to kill the pain and sleep around in the vain hope that the next man will end the isolation? But the next man is the isolation.

Between 1928 and 1939, Jean Rhys published four novels—Quartet, After Leaving Mr. Mackenzie, Voyage in the Dark, and Good Morning, Midnight—all of which exploit this sense of despair to the hilt. Let me paraphrase the feel of these books: A woman, somewhere between 25 and 45, lies on a bed in a half-darkened room in a hotel in a foreign city. Her clothes are well-made but worn-out, the hotel decent but run-down. She is broke, lonely, forsaken. She thinks about the room, how ugly it is. She thinks about her dress, how shabby it is. She thinks about the men in her life, how they’ve all promised love and all delivered betrayal. When she goes out, it is raining. There is nowhere to go and no one to see. She walks the streets in the rain. Somewhere along the way, she lets a man pick her up. Together, they buy a cheap bottle of wine, for which he pays, and go back to her room. Next morning, she is hungover, the man is gone, and she’s feeling all smashed up. Into this situation Rhys poured all her considerable talent, making of low-end sexual abandonment a parable of modern life.

Today, this proposition, as presented in these novels, feels dated: The protagonist seems simply neurasthenic, the circumstance irritatingly self-conscious, and the writer somehow only partially in command of her material. It would take nearly 30 years and the publication of a book that reads like nothing Rhys had ever before written to show what a superior talent saddled with an obsession can accomplish, if only it persists in working to get it right.

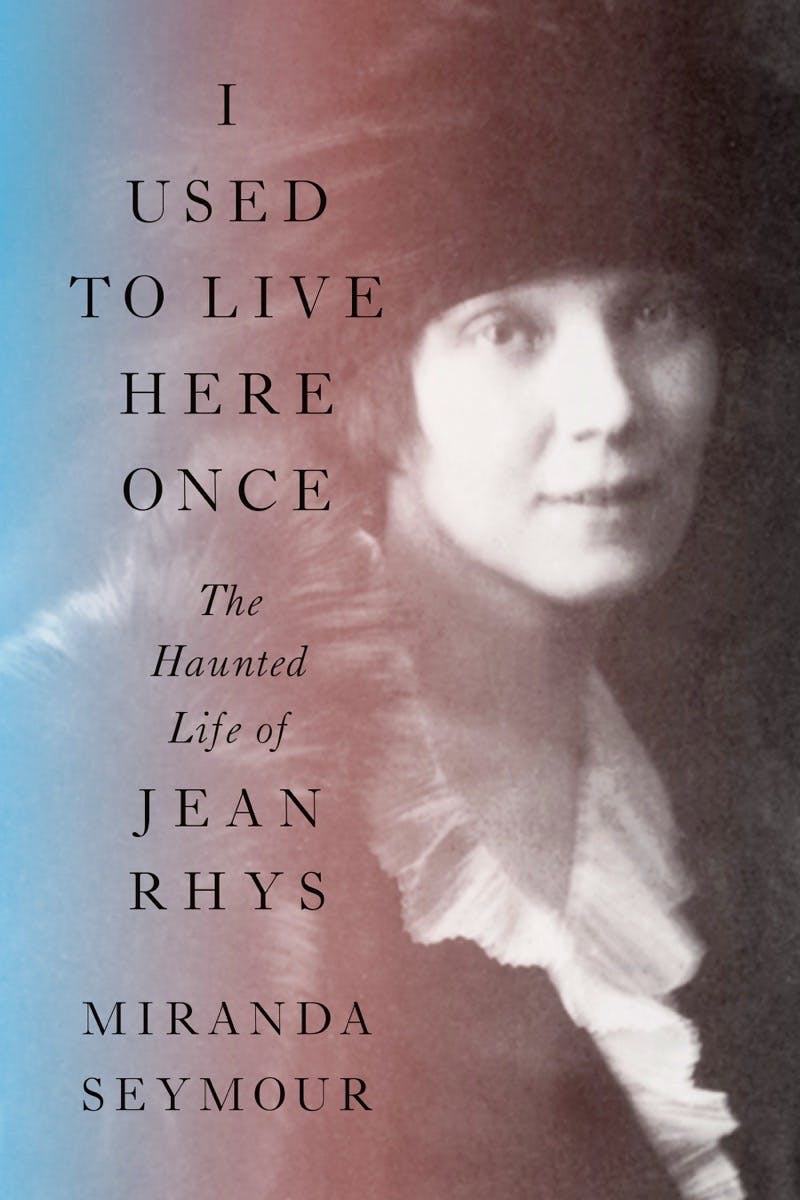

Jean Rhys was born Ella Gwendoline Rees Williams in 1890 on the Caribbean island of Dominica to a Welsh doctor and a third-generation Dominican woman of Scottish ancestry. According to Miranda Seymour’s new biography, I Used to Live Here Once, Rhys’s father adored her, while her mother “missed no opportunity to crush and humiliate” her. However, neither of these aspects of a complicated childhood can fully account for the fact that, from her earliest years, Rhys exhibited a kind of inborn wildness that resembled the transgressiveness of the outlier: the one destined for preternatural loneliness.

And then again, there was Dominica itself. She was growing up on an island where the memory of slavery—abolished in the 1830s—was still fresh, and where the hundred or so white colonials who remained after emancipation were increasingly insecure. A sense of shame dogged the family; the young Rhys faced being taunted in the street, Seymour writes, as “a white cockroach,” a member of the flailing oppressor class who somehow refused to leave. All this fed into a personality prone to defiance. Forever being scolded for not fitting in—“I’ve done my best,” her mother lamented. “You’ll never be like other people”—she’d fly into a rage and lash out mercilessly. Her many fits of outrageous behavior contributed heavily over the years to the isolation that she both feared and brought upon herself.

At 17, she left Dominica, never again to live on the island. She spent a year at high school in Cambridge, England, though made no plans to use her education. Like some small-town Midwesterner headed for Hollywood, Rhys believed she would go to London and immediately become a principal actor on the English stage. Of course, as it turned out, her acting talent was unremarkable. So what did she do next? She drank. Joined a sleazy touring company as a chorus girl. She left the company for a traumatic love affair with a wealthy man twice her age, who after a time cut her loose. She drank some more. She drifted for a couple of years, in all probability on occasion trading sex for money, Seymour suggests. She married a handsome Dutchman, a bigamist and small-time embezzler, who spent time in jail and on the run from the law. With him, she drifted even further.

All this while, she’d been writing down various accounts of her experiences in notebooks she carried around for years. She showed some of this work to a woman who knew Ford Madox Ford, then editor of The Transatlantic Review, in hopes that Ford might publish some of it, thereby somewhat relieving the money situation. Ford found the writing crude but exciting; very alive; endowed with the authority of lived experience. Not only did he publish some of it, he embarked on a tumultuous liaison with Rhys, arousing anew in her the association of desire with exploitation and betrayal. Nonetheless, it was under Ford’s tutelage that she began to write seriously. With writing came her great discovery of the redeeming value of literature, at whose shrine she worshipped throughout a relentlessly tawdry life.

But literary success was not—yet—in the cards for Jean Rhys. The four novels she published during the ’20s and ’30s brought a modest amount of attention and even more modest amount of money. Nothing changed, Ford abandoned her, she soldiered on. With the outbreak of World War II, she disappeared from London; her books went out of print, and she was forgotten. Twenty years later, an actress named Selma Vaz Dias, who wanted to dramatize Good Morning, Midnight on the radio, found her living in poverty and obscurity in the English countryside with a third husband who also ended an embezzler and a jailbird.

Now befriended by a pair of London book editors, Rhys was newly encouraged to write and, despite the extraordinary disorder of her daily life—never enough money, never enough heat, never a proper room in which to write—she pulled out a manuscript that she had been working on for some years, and began again. But Rhys being Rhys, she lied wildly to her editors—Diana Athill and Francis Wyndham—promising them for the better part of a decade that the manuscript would soon be ready. She’d go on an alcoholic tear and explain that the work was delayed because the roof was leaking, her typist had walked out on her, her husband was at death’s door—swearing that now she was back on the job, and they’d have the book in no time.

Published at last in 1966, Wide Sargasso Sea brought fame and fortune. Rhys’s books were reprinted, and when she died in 1979, she was a literary celebrity. And deservedly so. Wide Sargasso Sea is the book that brings together all the partially realized wisdom inherent in the other Rhys novels, and makes it count as it had not counted before. Here, it runs deep and it runs true.

In this novel, Rhys takes as a backstory a piece of the bare-bones plot of Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre. Mr. Rochester, a repressed Victorian, has come to the West Indies looking for a rich wife. He becomes engaged to Antoinette Cosway, a white Creole heiress, whose passion makes come alive in him an answering passion that shocks and frightens him. Repeatedly overcome by desire for her, he is repelled by himself, and soon withdraws sexually from her. His coldness drives her mad. He takes her back to England and locks her in the attic. She escapes and sets fire to the house.

Into this situation Rhys poured not only her gift for language and form, but an underlying sense of truth that had, at last, come to brilliant fruition. Out of her lifelong preoccupation with what passes erotically between men and women, there suddenly emerged a rich interiority that justified the half efforts of all the novels that had come before. We see for the first time not only the mutuality of the sexual engagement, we see the way things fall out for the man as well as the woman; and then we see further.

In a number of sections of Wide Sargasso Sea, Rochester is speaking directly to the reader. We see his raw sensuality blossom unaccompanied by love—“One afternoon the sight of a dress which she’d left lying on her bedroom floor made me breathless and savage with desire. When I was exhausted I turned away from her and slept, still without a word or a caress.” And we see his hunger for Antoinette wane: “I did not love her…. I felt very little tenderness for her, she was a stranger to me, a stranger who did not think or feel as I did.”

Soon, Antoinette and the island itself begin to merge in Rochester’s mind. In the worst way, they come to resemble each other. The place seems “not only wild, but menacing,” like her. And excessive, fantastically excessive: “Everything is too much, I felt…. Too much blue, too much purple, too much green. The flowers too red, the mountains too high, the hills too near. And the woman is a stranger. Her pleading expression annoys me.” And then he feels trapped: “I have not bought her, she has bought me.” He is thinking exactly as one imagines all the men in the earlier Rhys novels might have been thinking.

And she? Antoinette? She, too, is beside herself. Desperate to reawaken Rochester’s desire, she goes to her former nurse Christophine, to ask for an obeah potion that will restore his love. But the old nanny, refusing at first, says, “When man don’t love you, more you try, more he hate you, man like that.” We see how instrumental is Antoinette’s stake in the relationship; how profoundly she feels (without knowing it) that his passion is necessary to the achievement of her own sense of self; at the same time we also see—nay, feel—all this erotic primitivism bound up with the overwhelming fecundity of the island itself. Everywhere there is radiance and rot; everything overheated and overgrown, heavy with a malignant self-concern. The roads themselves are only clearings forever threatening to be sucked back into the encroaching forests. The loss of control over nature is complete. This is what Rhys had been trying to say for 40 years.

Rhys herself could not enjoy the late-in-life celebrity that Wide Sargasso Sea brought her; in no way could it wipe out the unutterable dreariness of the years behind this moment. Yet, to her everlasting credit, she never wavered in her love of literature, the only thing that lifted her from the permanent chaos in her head. It was this devotion that made her take years to deliver a book: She owed it to literature to work until she felt she’d got it right. A year or two from death, Rhys cried out at her friend, the novelist David Plante, “Oh David, I’m unhappy … all my life I’ve been so unhappy. It’s unfair … I’m dying, my body’s dying, and inside I think: it’s unfair. I’ve never lived, I’ve never lived.” But then she wiped her eyes, had another drink, and said to Plante, “Listen to me, I want to tell you something very important. All of writing is a huge lake. There are great rivers that feed the lake, like Tolstoy and Dostoevsky. And there are trickles, like Jean Rhys. All that matters is feeding the lake.… It is very important. Nothing else is important.”

I’ve always thought if it had not been for reading and writing, Jean Rhys could have become a transgressor of a serious sort: a thief, a pornographer, a husband killer. But there she is, on the one hand a highly neurotic alcoholic, on the other a priestess at the shrine of Art, and in between an intermittent but hardworking writer determined to make a book in the shape of clarified experience.