You’re not sure how long it’s been since you last heard from him. But when you get to be 70-whatever, you’re never sure how long anything is. You do remember that you’re both members of the Class of ’69 and that you smoked metric tons of weed between classes. And, no, dammit, it’s not a universally acknowledged truth that if you remember anything about the ’60s, you weren’t there! There was a whole lot to remember, especially the acres of music you guys locked into, no matter how ancient, arcane, or campy. And now, he’s dropping by again, as shaggy, disheveled, and loosely attired in denim as he was back in freshman year, only with whitecaps now breaking through his thick-as-ever beard. With the barest preliminaries, he plops down the armloads of LPs he’s lugged from the minivan parked in your driveway, and you’re ready to spend the weekend living your lives over again on your beat-up turntable.

The playlists sprawl through genres and eras. Of course, there’s Elvis; only not just Presley (“Money Honey,” “Viva Las Vegas”) but also Costello (“Pump It Up”), along with generational touchstones: Carl Perkins’s “Blue Suede Shoes,” the Grateful Dead’s “Truckin’,” Ray Charles’s “I’ve Got a Woman,” Little Richard’s “Tutti-Frutti” and “Long Tall Sally,” the Who’s “My Generation.” Then there’s all the postgrad ’70s stuff, some of it more durable than expected: Jackson Browne’s “The Pretender,” Harold Melvin & the Blue Notes’ “If You Don’t Know Me by Now,” the Allman Brothers Band’s “Midnight Rider,” and—why the hell not?—the Eagles’ “Witchy Woman.”

And, as always, there are the eruptions where each of you wonders whether the other has lost his mind. Really, man? “Whiffenpoof Song”? By Bing Crosby? Johnnie Ray’s “The Little White Cloud That Cried”? Dean Martin’s take on “Blue Moon” (and not the one by the Marcels)? And Cher’s “Gypsys, Tramps & Thieves”? What are all those people doing mixed up in this batch with the Fugs’ “C.I.A. Man” or Nina Simone’s “Don’t Let Me Be Misunderstood”? We got to have a Sinatra, but “Strangers in the Night”? Even he didn’t dig that tune! Still, good call on Mose Allison’s “Everybody Cryin’ Mercy” and Bobby Bare’s “Detroit City.” You could go on and on like this all day, all night, all year.

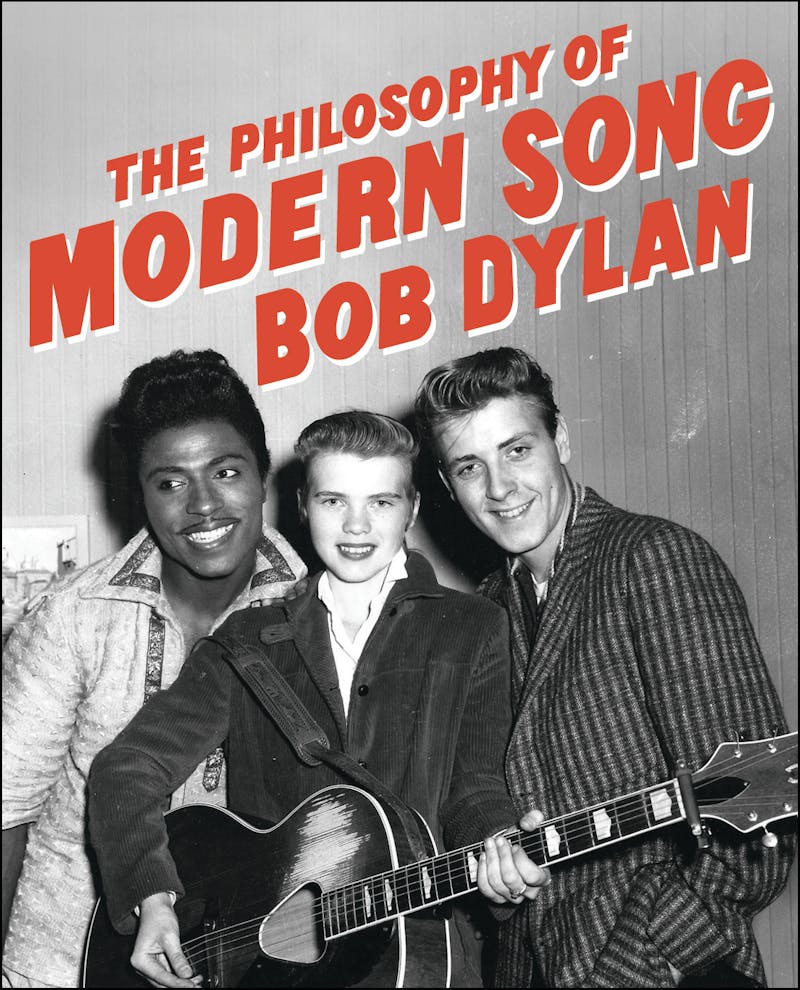

The more time one spends wandering around the Proustian jukebox that is Bob Dylan’s The Philosophy of Modern Song, the more tempted one is to imagine it resembling a marathon listening party with a college friend—eclectic, shaggy, and impish, if a tad more inscrutable than anybody’s best friend would dare. These song titles are among 66 that Dylan has selected for his idiosyncratic, compulsively epigrammatic survey of popular music, reaching as far back as “Nelly Was a Lady,” written in 1849. Scholars, along with mandarins, culture cops, and other spoilsports, might propose that Dylan needed to produce a book of this ambition and scope to validate his 2016 Nobel Prize in literature. For some, it still won’t be enough without even a semiformal statement of purpose, detailing whatever it is he’s trying to do and just how “philosophical” he intends to be.

Yet Dylan has never been interested in anything so straightforward as explaining himself. The Philosophy of Modern Song, among myriad other things, is an elaborately apportioned thank-you card from its author for everything the craft of song has given him through his 81 years on Earth. Though its title suggests a system of thought itself as a skeleton key to how genres and subgenres of popular music fit into each other, the book is far too subjective and far too personal a document to be viewed as pure history or, as some would have it, pop criticism. It is, instead, pure Dylan in its allusive, dreamlike musings, each of them digressing and spinning into the strange or exotic in the manner of Dylan songs like “Just Like Tom Thumb’s Blues,” “Maggie’s Farm,” or “Idiot Wind.” If, for Leonard Cohen, songs made up a tower, songs for Dylan are a Monument Valley of varied terrain and big skies, with plenty of room for him to project his own mind-movies, submit his own testimony as to how these songs came to be, where they landed, and what can be deciphered from their echoes.

Song lyrics, Dylan considers, can appear “slight” when written on the page. “But it’s important to remember,” he adds, “that these words were written for the ear and not for the eye. And as in comedy, where a seemingly simple sentence can transform into a joke through the magic of performance, an inexplicable thing happens when words are set to music. The miracle is in their union.”

In his pieces on each song, Dylan often tries to preserve their unquantifiable appeal rather than aiming to pin down their own essence and explain what makes them work. Marty Robbins’s 1959 “El Paso” “hardly says anything you understand,” he writes, “but if you throw in the signs, symbols, and shapes, it hardly says anything that you don’t understand.” I’m not sure his assessment applies to Robbins’s pulp Western romance, whose narrative elements are as straightforward as a roadside diner’s breakfast special. But as a gateway to how Dylan hears music, it reveals almost everything about the digressions, speculations, and postulations spinning in each of these 66 case studies.

Conviction goes a long way with Dylan, no matter where it comes from. Early in the book, he turns to Perry Como’s 1951 “Without a Song.” (“That field of corn would never see a plow / That field of corn would be deserted now / A young one’s born, but he’s no good no how / Without a song.”) He introduces Como as “the anti-American Idol”:

He is anti–flavor of the week, anti-hot list, and anti-bling. He was a Cadillac before the tail fins; a Colt .45, not a Glock; steak and potatoes, not California cuisine. Perry Como stands and delivers. No artifice, no forcing one syllable to spread itself thin along many notes.

In the folklore of mid–twentieth-century pop culture, Perry Como is the King of Melted Cheese, “Mister Nice Guy,” the dulcet, double-knit embodiment of suburban dream life. Dylan might be picking fights right off the bat by placing such a figure, the antithesis to the disorderly energies of rock and roll, near the foreground of his Philosophy. But is he? True, Como wasn’t Elvis or Little Richard, but, as Dylan suggests, Como was his own distinctive brand of existential hero, a durable avatar of the job well done. No social protest, no hyper-realistic vision can sustain itself without the tempered fluidity found in a Perry Como performance. Dylan is dispatching alerts to his readers early in the game: Flash-freeze your biases and forget whatever you think you know. Perry Como is a guru of having a life’s purpose. Maybe he wouldn’t put it that way, and neither would Dylan. But Dylan’s challenge here is to anybody who thinks they’ve got it all figured out in advance. You think Perry Como’s a square? Then what, or who, does that make Dylan? Or you?

Dylan’s discussion of “Without a Song” itself is more cryptic. He begins, opaquely, by observing that the lyrics don’t “really name the song that the world would be worse off if it never heard.” He just writes it off as a “mystery,” one of many, swirling throughout the book, that you’ll have to either untangle or accept.

Dylan tends to let the reader draw their own associations. Trot over to left field, for instance, with Vic Damone’s 1956 version of “On the Street Where You Live” from My Fair Lady. Dylan’s exegesis is accompanied by a wedding photo with Damone as the groom and the ill-starred film actress Pier Angeli as the bride, taken in the fall of 1954. On the next page, there are two photos of James Dean with Angeli, whom Dylan characterizes as “the love of James Dean’s life.” You’d have to go online to find out that Dean and Angeli dated between 1952 and 1953, and that Angeli and Damone married in the fall of 1954. You find out from Dylan that Dean “waited across the street on his motorcycle on [her] wedding day.” Recalling the song’s premise—of a young man returning time and again to the block of the girl he loves—Dylan suggests at the very end of this meditation, “Maybe for the rest of his short life, this was a song that belonged to James Dean.” OK. A song that was part of a musical that didn’t open on Broadway until six months after Dean died in a car crash belonged to him? I’m buying in. Seriously.

Context can only take you so far in this seminar. Why should it? Unless you can create one where no one else thought to look. In a compendium of virtuoso spritzing, the weirdest, most inspired performance could well be the six pages Dylan devotes to Santana’s 1970 recording “Black Magic Woman,” which was written two years earlier by Fleetwood Mac’s Peter Green. He sees the song’s titular figure as “a hard case, full of mumbo jumbo and her kisses have a pungent smell.” There isn’t much Dylan can do to evoke a phantasmagorical “Black Magic Woman” more vividly than the song does. Instead, he nerds out with a portrait of a true-life “black magic woman”: the prolific and versatile science-fiction novelist and screenwriter Leigh Brackett (1915–1978), whose film credits include The Big Sleep, Rio Bravo, and The Empire Strikes Back, and whose science-fiction and fantasy books include 1955’s The Long Tomorrow and 1953’s The Sword of Rhiannon, set in the ruins of an ancient Martian civilization that figured out high-tech millions of years before Earth.

To be clear, Dylan’s not saying Brackett is the woman who literally inspired the song, but someone the song brought to (his) mind, yet another stretch of free association sneaking into the symposium from another quadrant of the pop cultural universe. Dylan is especially struck that The Sword of Rhiannon “presaged” one of Arthur C. Clarke’s three laws of science fiction: “Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.” Or as Dylan quotes directly from Brackett, “Witchcraft to the ignorant … simple science to the learned.” For Dylan, this distinction between science and magic also helps define music, the one “place where additional learning does not disentangle the mystery of the subject.” It’s the kind of gnomic observation that at once opens and closes off possibilities for elaboration. He submits a variation on music’s mystery, but neither offers a clue nor shows an inclination to solve it.

What is most stunning, though it shouldn’t be, is the tenderness Dylan often displays toward his fellow craftsman; compassion that is especially evident in his back-to-back appreciations of Warren Zevon and John Trudell. He extols Zevon’s “Dirty Life and Times,” the opening track from his last album—released in 2003, the year he died—as a “great record,” adding the rueful observation that “the braggart, the roué, the ironic observer, and the inebriated fool were all roles Zevon chose to play in his songs. And possibly at times in his life. But stripped to the bone, as in this song, the artistry jumps out at you like spring-loaded snakes from a gag jar of peanut brittle.”

The lesser-known but deeply respected Trudell, who died of cancer in 2015 at 69, was an Indigenous American poet, actor, and activist who was a leader of the 1969 takeover of Alcatraz Island. To honor his memory, Dylan chooses “Doesn’t Hurt Anymore” (2001), a part-spoken, part-sung lament that lists, in Dylan’s words, “a million ways to go mad” that impede the determination to endure. “John was not mainstream,” Dylan writes. “He didn’t talk about popular subjects like hustling drugs, pimping, and materialism, glorifying those things. John’s music can elevate you and usually does. Maybe there isn’t a place for that.”

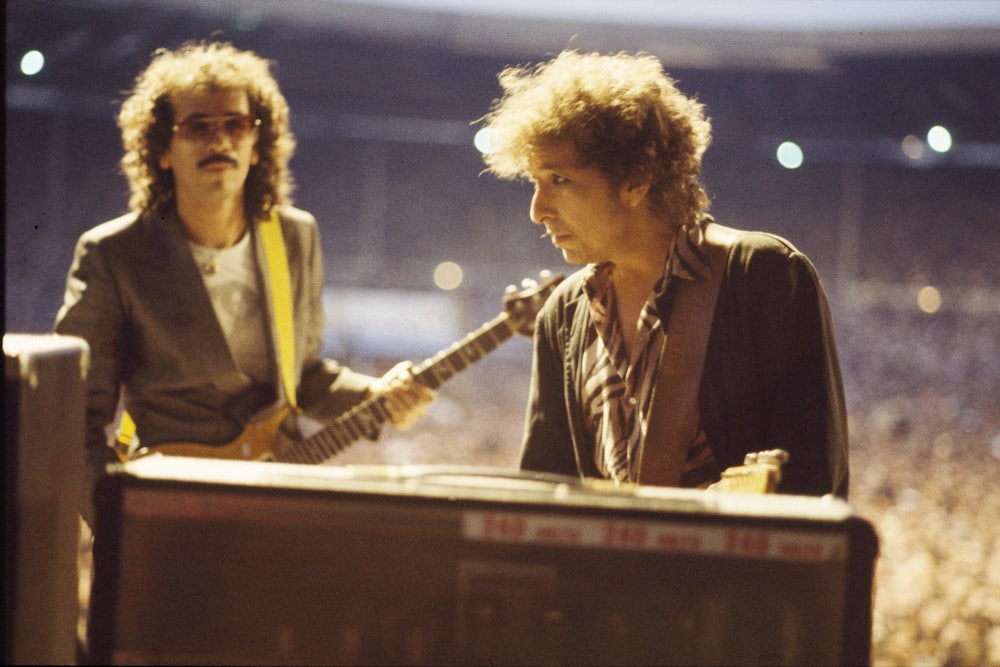

He’s talking here, sadly, about the marketplace. Some of the more poignant photos illustrating The Philosophy of Modern Song, including the back cover, are period photos of people shopping for brand-new vinyl records; there’s even a frontispiece spread of workers in the Columbia record factory sliding LPs into slipcovers. These images float around the other archival artwork and textual observations like furtive dreams of a more economically prosperous post–World War II era of unprecedented growth in mass communications; nostalgic not just for a booming record industry, but for the means through which music was marketed and sold.

These were the circumstances that allowed Bob Dylan’s ascension; they allowed him, also, to define and reshape his public persona, his musical ideology, even his own mythology. Such a time seems remote from our own. Even if post-millennial technology provides all kinds of the machinery, digital or otherwise, for pop celebrity to lay siege to public consciousness, few of us can say with any certainty how “selling records” works now—or what, for that matter, a “record” is. The Philosophy of Modern Song, much like the ruins of the Martian civilization in Leigh Brackett’s book, is an artifact of arcane magical processes that seem out of reach, yet still familiar enough to recollect, if not revive.

Though Dylan promises philosophy, he never really sets out an accounting of his worldview—and he doesn’t have to. Has anybody else come up with a line that evokes the specter of late–twentieth-century inertia as neatly and frighteningly as, “We sit here stranded, though we’re all doing our best to deny it”? I’d put up any song or lyric from 1965’s Bringing It All Back Home against, or alongside, a given Nobelist’s literary work from the same period for the way its recorded texts jar their listeners toward wide-eyed radiance. There are in “Subterranean Homesick Blues,” “Gates of Eden,” or “It’s Alright, Ma (I’m Only Bleeding)” rapid-fire mosaics of the prophetic, the apocalyptic, and the aphoristic; sometimes, all three at once, as in the deathless assertion “that he not busy being born is busy dying.”

The song lyrics of the ’60s and ’70s (and not just Dylan’s) were so directly, intricately entwined with their time and their generation’s collective unconscious that many of us too young to know any better believed calling them “song lyrics” was reductive, even cheapening, when measured against the higher calling of poetry. At their best, Dylan’s engagements with the metaphysical and the suggestive, along with more declamatory jabs at the body politic like “Blowin’ in the Wind” or “The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll,” revived a tradition of songs as self-contained vehicles for sweeping, absorbing adventure, like novels and movies. But whatever profundities there were to draw from their content, whatever mysteries were weaved within their core, Dylan’s songs were still, essentially, songs—even if you wished to dive into them to comb for secrets to the universe, if not whole universes themselves.