Given the kind of offenses listed on Henry Kissinger’s bill of indictment, buckraking might seem less significant compared to the Everest-sized mountain of dead human bodies left by the various policies he advocated over the years. But it’s worth considering the impact of this practice on U.S. foreign policymaking.

When I was hired as a researcher at the Center for American Progress in 2008, about a year after having arrived in Washington, I noticed something strange about a some of my senior colleagues, many of whom had previously served in government and hoped to again. In addition to their titles, their bios noted that they were also senior advisers at various consultancies and management firms servicing large corporate and international clients. This struck me then as a potential conflict of interest. Oh well, I thought, I guess that’s how it’s done in this town.

In retrospect, I was right on both counts. It is a very clear potential conflict of interest. And that is, in fact, unfortunately how it’s too often done in Washington. And to some extent we have Henry Kissinger to thank for it.

Obviously, U.S. corporate and government power have always been closely mingled in both foreign and domestic policy. The United States was knocking over governments for the benefit of the U.S. financial sector while claiming to defend freedom and stability well before Kissinger ever gained influence. But Kissinger was the first to really show how the celebrity bestowed by government power could be parlayed into a massively profitable post-government career as a paid adviser to powerful multinational corporations and foreign governments.

Describing the thinking behind the new phenomenon in a 1986 piece, Les Gelb, a former U.S. official turned New York Times national security correspondent who would later serve as the president of the Council on Foreign Relations, wrote, “Many of these former Government leaders asked themselves, why not capitalize on our stardom, international contacts, and inside knowledge to make large incomes on our own?”

They answered their own question by going out and doing just that, and Henry the K led the pack. “Kissinger’s 41 years of consulting service include American Express, Fiat, Rio Tino, Lehman Brothers, Merck, Heinz, Volvo and JP Morgan,” Ben Judah, a leading expert on kleptocracy and anti-corruption, tweeted recently. “His business career was truly pioneering in Washington.”

In recent decades, numerous “strategic consulting” firms have been launched by big foreign policy names. “Kissinger helped normalize this dynamic of being a consultant to big business and a public policy voice,” wrote Vox’s Jonathan Guyer, whose reporting has tracked the rise of these firms and their influence on policymaking. Guyer homes in on the key question: “Is it ethical for a former senior official to continue to serve on federal advisory boards that give policy recommendations to the Pentagon, the State Department, or the president while also advising companies that are likely to profit from those geopolitical decisions?”

The foreign policy establishment seems to have definitively answered that question in the affirmative. And that poses a problem for our foreign policy, as it gives powerful, wealthy, and unaccountable interests yet more avenues for influence in a political system that’s already heavily gamed in their favor.

The Washington foreign policy consensus toward China has radically shifted over the past few years, but for decades Kissinger was at the forefront of the effort to open China to U.S. business interests, using his status as elder statesman to downplay concerns about the Chinese government’s human rights abuses or unfair trade practices that could have created inconvenient pressure for those business interests. It’s hard to believe that Kissinger wasn’t shading his public statements or his private advice to administrations that continued to seek it in ways that benefited his clients, but that’s the point: We really shouldn’t have to wonder.

It’s worth remembering that, upon being named as head of the 9/11 Commission by President George W. Bush in 2002, Kissinger faced serious questions from families of 9/11 victims over potential conflicts of interests posed by financial relationships with governments that could be implicated in the commission’s work. Kissinger eventually resigned from the commission rather than publicly disclose his clients. The 9/11 investigation provided a particularly harsh spotlight, but the fact is that these same questions could reasonably be asked of every administration official with these kinds of business relationships.

The uncomfortable truth is Biden administration’s foreign policy team includes numerous people with these potential conflicts. It gives me no pleasure to point this out. I know a lot of these folks. I consider some of them good friends. They are skilled and well-intentioned public servants. But we must recognize that the cozy relationships between corporate interests and former and future foreign policymakers, and the very legitimate questions those relationships raise about whose interests are really being looked after, is a problem for our foreign policy.

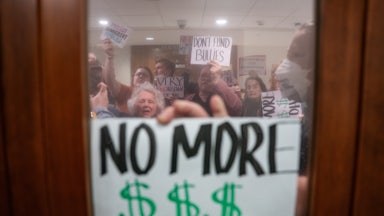

It’s also corrosive to democracy. Polling shows that Americans’ trust in government remains extremely low. In a 2022 survey by the Partnership for Public Service, 56 percent of poll respondents said they did not trust the government much or at all. Half said that the government mostly helped the wealthy. This is fertile ground for authoritarian demagogues to sow anger and distrust in democracy and reap support by selling themselves as the only ones who can fix it. To his credit, President Biden has recognized restoring trust in government as a core challenge. But thus far the steps to address it at a systemic level have been meager.

It would of course be wrong to lay the broader problems with American democracy at Henry Kissinger’s feet. (To do so would be to impute a level of influence that would surely delight him.) Corporate interests from our defense industry, finance, and other sectors all lobby the administration heavily. And again, these issues pale in comparison to the various acts of violence and sabotage that Kissinger supported and enabled while in power. But while those acts undermined U.S. credibility abroad, the dominance of wealthy, unaccountable interests in all levels of our politics undermines the functioning of our democracy, which has implications both abroad and at home. Anyone who is committed to preserving and strengthening that democracy for future generations must take it seriously, even if confronting it means hurting some of our friends’ feelings.