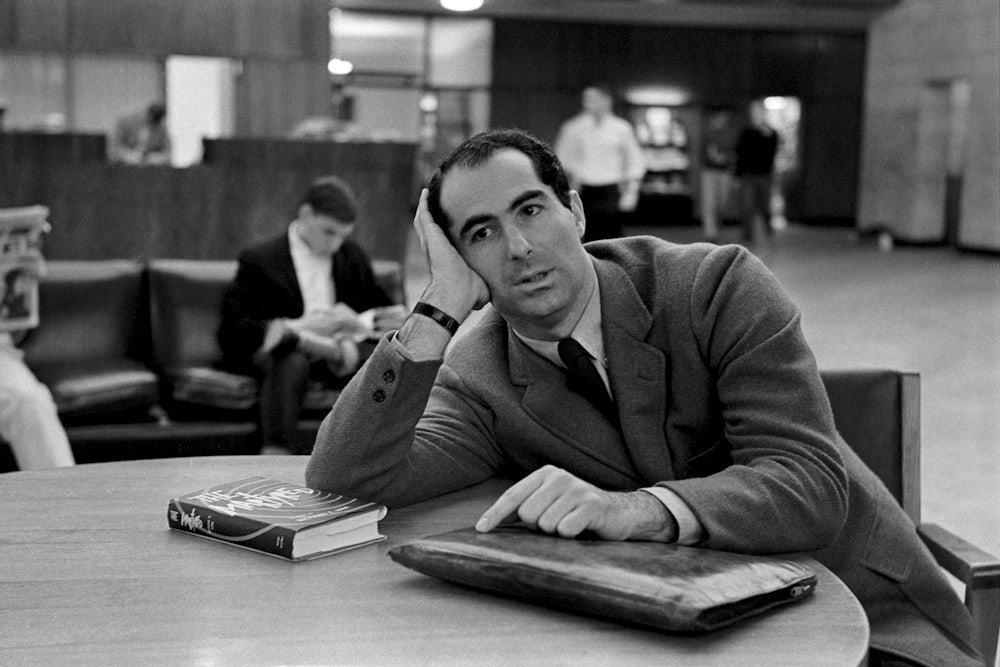

Humor is not the primary métier of The New Republic nor, for that matter, of liberalism. But there’s a small tradition that includes this cute, fairly mild satire by a very young Philip Roth, mocking both Eisenhower and the Power of Positive Thinking. During the seventies, Woody Allen wrote regular send-ups for the magazine. The magazine most regularly deployed humor, and to great effect, during the eighties and nineties, a period when it gleefully attempted to overthrow the oppressive orthodoxies of liberalism. It was a style that fit the cause.

—Franklin Foer, former TNR editor, Insurrections of the Mind: 100 Years of Politics and Culture in America

... He [Congressman Walter Judd of Minnesota] told me this fascinating story about President Eisenhower. Mrs. Judd had been having a visit with Mrs. Eisenhower who told her, “Ike goes into bed, lies back on the pillow, and prays out loud, something like this: ‘Lord, I want to thank You for helping me today. You really stuck by me. I know, Lord, that I muffed a few and I’m sorry about that. But both the ones we did all right and the ones we muffed I am turning them all over to You. You take over from here. Good night, Lord, I’m going to sleep.’ And,” added the President’s wife to Mrs. Judd, “that is just what he does; he just turns over and goes to sleep ...”

NORMAN VINCENT PEALE, DECEMBER, 1956

The man of deep religious conscience and conviction traditionally speaks to his God with words of awe, love, fear, and wonder: he lifts his voice to the mysterious bigger-than-space, longer-than-time God, and his own finiteness, ignorance, and sinfulness grip his spirit and carve for his tongue a language of humility. Only recently Mrs. Eisenhower revealed to a White House guest the words the President himself speaks each night to the Lord from the quiet of his bed. As the President himself is half-way through his fifth year in office, it would perhaps be fitting to examine the short prayer which has helped to carry him through to the present, the prayer with which he attempts to crash through the barriers of flesh and finitude in his quest for communion with God.

To imagine the tone of voice with which the President delivers his prayers one need only read the closing sentences as Mrs. Eisenhower reports them. “You take over from here,” the President says aloud. “Good night, Lord, I’m going to sleep.” The President’s tone is clear: if one were to substitute the word “James” for “Lord” one might hear the voice of a man calling not to his God, but to his valet. “I have polished my left shoe, James. As for the right, well—you take over from here. Good night, James, I’m going to sleep.” The tone is a chummy one, as opposed, say, to the tone taken toward Cinderella by her despised stepsisters; “Sweep the floor, wash the clothes, polish the shoes, and then get the hell out of here ...” The President addresses his valet as he does his God, as an equal. Where the theologian, Martin Buber, has suggested that man is related to his God as an “I” to a “Thou,” Mr. Eisenhower’s tone would seem to suggest that the I and Thou of Buber’s thinking be converted into the more democratic You and Me.

“Lord,” the President’s prayer begins, “I want to thank You for helping me today. You really stuck by me ...” The Lord is not so much his shepherd, Mr. Eisenhower indicates, as his helper, his aide-de-camp. He is a kind of celestial Secretary of State, and one who apparently knows his place in the chain of command; it is quite clearly stated, “You stuck by me” and not “I stuck by you.” The prayer continues, “I know, Lord, that I muffed a few and I’m sorry about that. But both the ones we did all right and the ones we muffed I am turning them all over to You.” A slight ambiguity exists around the words “a few.” A few what? Does Mr. Eisenhower mean decisions? And how many are a few? If, as we are led to suspect, the Lord works hand in hand with the President, then such questions are academic, for God would doubtless know precisely the decisions to which Mr. Eisenhower is alluding. Of course one cannot dismiss the possibility that all this mystery is intentional, as a sort of security measure. You will remember that Mrs. Eisenhower is no more than a few feet away, listening to every word.

Uncertain as he may appear as to the nature and number of the decisions, the President leaves no doubt as to how the decisions are formulated: it is a bipartisan set-up, the President and God working together right down the line. What seems unusual about the procedure is that while both share the responsibility for the successful ventures (“the ones we did all right”), the burden of failure falls rather singly upon the Shoulders of the Lord. Though admittedly “sorry” about muffing a few, Mr. Eisenhower informs the Lord point-blank, “I am turning them all over to You.” Now nobility in defeat is a glorious spectacle—it is what immortalizes Oedipus and Othello, Socrates and Lincoln. The vision of a soul alone in the night confessing to his God that he has failed Him is in a way the tragic vision, the supreme gesture of humility and courage. However, to admit failure is one thing, and to sneak out on a partnership is another. If the once flourishing business of X and Y suddenly tumbles into bankruptcy, Y does not expect that X will put on his hat and gloves and walk out muttering, “I’ll see you—you pay the creditors whatever it is we owe them. Bye, bye ...” One should think that X and Y must pay the debts just as they had shared the profits: together.

Perhaps it is unjust to draw any implications from an analogy which is, I fear, not entirely appropriate. For instance, in the X and Y example it is assumed that the initial capital for the enterprise had been supplied equally by both X and Y; now whether or not this is analogous to the Eisenhower-God relationship is uncertain-as yet evidence released by the White House staff is not sufficient for any but the most zealous to conclude that the Chief Executive shared in either the planning or execution of the Original Creation. Moreover, I am confident that a religious consciousness like the President’s, which manifests itself in prayer and good works, would be outraged at the notion of God as a partner; though the Lord is addressed as an equal, and functions as a helper, His ultimate powers, Mr. Eisenhower well knows, are those of a superior. Surely the President would be the first to remind us that he himself is in the service of the Lord, as are we all. The vital question then is not the responsibility of partner to partner but of subordinate to superior, worker to boss. Perhaps Mr. Eisenhower’s own history, as a halfback on the West Point football team and as a professional soldier, can provide analogies more appropriate to this problem.

Imagine, for example, that the Army football team has been beaten by Navy, 56 to 0; the quarterback returns to the bench and explains to the Coach, “Coach, I muffed a few and I’m sorry about that. But both the ones we did all right and the ones we muffed I am turning them all over to You.” Or picture a Colonel whose regiment has suffered disastrous and unpardonable losses; he is summoned to divisional headquarters; he enters the office of the Commanding General; he salutes; he speaks: “Sir, I muffed a few and I’m sorry about that,” he admits. “But,” he adds quickly, “both the ones we did all right and the ones we muffed I am turning them all over to You.”

Anyone who has ever played left guard for a grade school team or toiled at KP in a company mess hall could conjecture the answer of both coach and general; as for the reaction of the Lord to so novel a concept of responsibility, my limited acquaintance with historical theology does not permit of conjecture. Off the cuff, I imagine it might strain even His infinite mercy.

Mrs. Eisenhower reports that when the President ends his prayer, “he just turns over and goes to sleep.” I suspect at this point the First Lady is not telling the whole truth, her own humility in operation now. The way I figure it, when the President has finished his man-to-man talk with the Lord, he removes his gaze from the ceiling of the White House bedroom, pauses for a moment, and then looking upward again, says, “And now, Lord, Mrs. Eisenhower would like a few words with You.” And then with that grin of his he turns to the First Lady and whispers, “He’s ready ...”