In October

2020, just a few weeks before he would defeat President Donald Trump, Joe Biden

made his clearest statement yet on whether Democrats—if so empowered by

voters—should expand the Supreme Court. “I’m not a fan of court-packing, but I

don’t want to get off on that whole issue,” Biden said. “I

want to keep focused. The president would love nothing better than to fight

about whether or not I would, in fact, pack the court or not pack the court.”

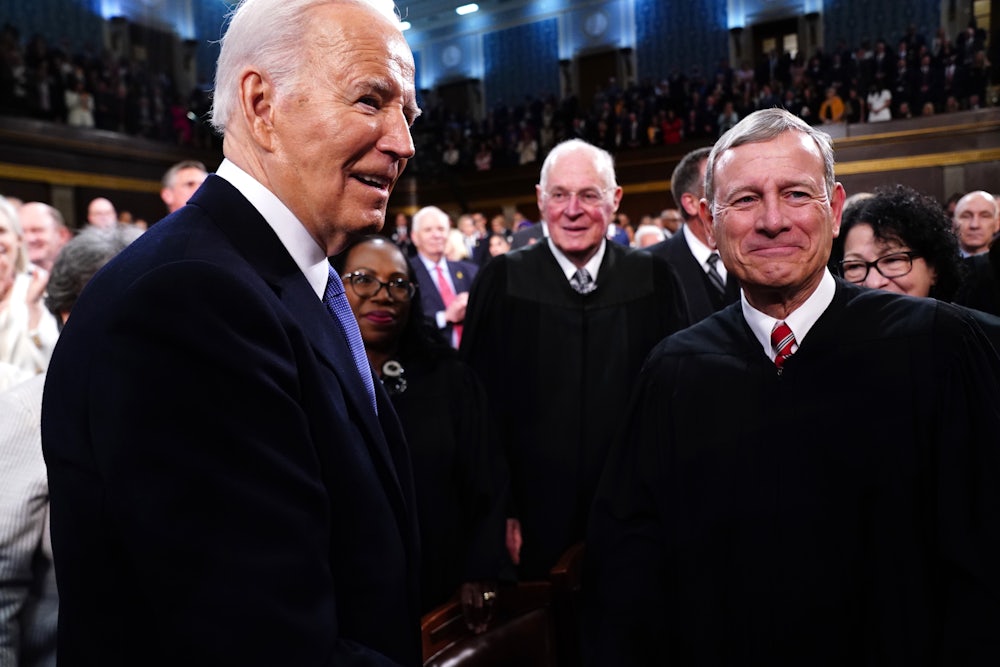

But Republicans had already packed the court. Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s death handed President Trump the third opportunity to appoint a justice (Amy Coney Barrett) and thereby to create a 6–3 archconservative majority on the court for a generation or more. Many understood then that such a lopsided court could do untold damage to the progressive accomplishments of the past century. But Biden, ever the institutionalist, squashed the notion of rebalancing the court in the unlikely event that Democrats won unified control of Washington. The unlikely did, of course, happen: Democrats took the White House and both chambers of Congress. And still, Biden demurred on court rebalancing. That was a mistake.

In the United States, the courts, especially the Supreme Court, play a critical role in making our entire system of government work. While Congress makes laws, and the president executes them, it is the court that enforces them. If its job is well done, it is accomplished out of the limelight. Occasionally it might be necessary for the court to intervene on substantial or pressing issues, but its normal business should be quiet, efficient, uncontroversial.

Over the past two decades, and especially since 2021, the Roberts court has instead made headlines, overturning federal and state laws, some of them in place for a hundred years or more, and reversing earlier major court decisions. The court has upended the ability of government agencies to do their jobs—to regulate clean air and water, limit the taking of bribes (by this court now redefined as “gratuities”), protect consumers and workers, and so much more. It has redefined human rights, undercutting the right to vote and the right to an abortion. In conversations with law professors across their country, I hear despair: How are they even supposed to teach administrative or constitutional law? There are no standards anymore.

These Supreme Court decisions have been based on tortured originalist readings. While one might disagree with the outcome, and the extent of the intervention, at least one felt there was a certain logic behind these cases, a logic by which the decisions could be engaged and challenged. But the decision in Trump v. United States had no such reasoning, not even a pretense of constitutional interpretation. The sweeping decision, more than any other over the past decade and more, exposed a raw partisanship and lack of principle. It not only set a dramatic new precedent that changes 235 years of understanding about the role of the president but it rewrote the Constitution, unbalancing it in favor of the president—and without apology. It made no pretense of considering the potential costs or risks of its dramatic intervention, as has been the norm for major Supreme Court decisions. It arguably removed most checks on presidential power.

Biden could have tried to stop such judicial overreach in 2021 by pushing to amend the Judiciary Act, which sets the size of the Supreme Court. (In April of that year, House Democrats put forth a bill to do exactly that, expanding the court to 12 associate justices.) He chose not to, opting instead to create a court reform commission, whose members were divided on expanding the court. That group’s final report summarized many of the arguments in favor of expansion, especially the extraordinary actions by then–Majority Leader Mitch McConnell to refuse to consider Obama’s nomination of Merrick Garland. But then they listed concerns. Some scholars argued that expanding the court for partisan reasons would merely lead to a cycle of tit for tat, undermining the court’s legitimacy. Ultimately they decided not to recommend it.

Three years later, the validity of such arguments has vaporized. Repeatedly, the court has overturned policy after policy, law after law, stifling the Biden administration’s efforts on many fronts, undoing decades of precedents. Republican court-packing has led to decisions that go far beyond the worst fears of 2020. Most importantly, the majority on the court has revealed, in the principled emptiness of its decision in Trump v. U.S. (not to mention others in the past few weeks), that it is openly partisan. The Roberts court, and the three Trump justices, have created chaos throughout our justice system and society, and undermined the court’s legitimacy. They need to be checked.

Congress, under the Constitution, is the most important branch, with almost half the text of the Constitution (2,268 words) devoted to its many roles. The presidency takes up only 1,025 words. The Supreme Court’s role, however, is third, with only 377 words. That’s because the Framers left much up to Congress to determine. The Constitution recognizes the court’s role as guardian but leaves its oversight up to Congress—including the size of the court.

Reforming the size of the court has happened many times over the years. Seven times between 1801 and 1869, Congress changed the size of the court, going from a low of five justices in 1801 to a high of 10 in 1863. In most of those cases, as in 1801 and 1863, the size went up and down in order to fix an imbalance or overreach by the Supreme Court. In 1863 and 1867, revisions to the Judiciary Act sought to rein in a Supreme Court that was potentially pro-slavery. Now we need to rein in one that is pro-authoritarian.

The question of judges overreaching, and assuming legislative or executive power, was of deep concern to the Founders (though to some more than others). In his autobiography, Thomas Jefferson noted that all judges in the colonial period had their positions at the pleasure of royal governors and the king, and that “a Judiciary dependent on the will of the King had proved itself the most oppressive of all tools.” That is why state and federal Constitutions specified that judges should have “the tenure of good behavior.” But, Jefferson continued, such concerns about the overreach of the new “executive Magistrate[s]”—that is, governors and presidents—meant that they made a mistake in these constitutions in requiring two-thirds of the Senate to vote for impeachment. Jefferson saw that this bar was too high, after the failed impeachment of Justice Samuel Chase in 1804 (while Jefferson was president): It was “a vote so impossible where any defense is made, before men of ordinary prejudices & passions, that our judges are effectually independent of the nation.”

Jefferson emphasized how power corrupts judges: “It is not enough that honest men are appointed judges. All know the influence of interest on the mind of man, and how unconsciously his judgment is warped by that influence. To this bias add that of the esprit de corps, of their peculiar maxim and creed that ‘it is the office of a good judge to enlarge his jurisdiction.’” The concern is that “they are in the habit of going out of the question before them, to throw an anchor ahead and grapple further hold for future advances of power.” With such self-interest in expanding their authority, “how can we expect impartial decision”?

Jefferson concluded that checking the power of judges was crucial to the balance of power in general. “I do not charge the judges with willful and ill-intentioned error; but honest error must be arrested where its toleration leads to public ruin. As, for the safety of society, we commit honest maniacs to Bedlam, so judges should be withdrawn from their bench, whose erroneous biases are leading us to dissolution. It may indeed injure them in fame or in fortune; but it saves the republic, which is the first and supreme law.”

Practically speaking, as Jefferson pointed out, impeaching judges is nearly impossible. Other methods of checking them, including a more vigorous ethics code, would be difficult to enforce precisely because of that bar. The other suggested reform, one also now on the table, is to limit the tenure of justices to a term, such as 18 years. Term limits are normal for high court justices in all states, and while life tenure during good behavior has been the norm, life is not specified in the Constitution. These questions, like the organization of the courts themselves, are left up to Congress.

One example often quoted by those who advocate against court expansion is that Franklin Roosevelt tried and failed to expand the court in 1937, after the court repeatedly overruled parts of his New Deal. Roosevelt wanted to add one new member for each justice over 70 who refused to retire. Opposition to his plan became a major political issue. The concern was that in adding so many members to the court, he would neutralize its power. While Roosevelt lost that fight, he won the battle, in that the Supreme Court ceased to act so aggressively to overturn legislation.

At this moment, a bill is on the table to expand the size of the court to 12 associate justices, which would match the number of justices to the number of circuit courts, thus giving each justice primary responsibility for decisions from one circuit. Right now, the justices are overloaded, with too much responsibility. Expanding the court makes pragmatic and logical sense, and could happen gradually; Congress could allow the nomination of two justices now and another two in four years.

The concerns of 1937, or of 2020, about increasing the size of the court have now been neutralized by this court’s unprincipled overreach. While the full consequences of all the court’s recent decisions are yet to be seen, they will impact all of us, and increasingly so, given the courts’ essential role in enforcing the laws. Regardless of where one stands on the political spectrum, all should now see that the unprincipled political maneuvering that created the current majority on the Supreme Court has undermined our system of government.

We need new, principled judges to keep the extremist justices on the Robert’s court, and now the newly empowered president, in line. Many Democrats in Congress grasp their constitutional responsibility to regulate the judiciary, and are willing to exercise it to rebalance the Supreme Court. Now it needs to become a central part of the Democratic platform. Biden and his team need to wake up. It is not enough to merely dissent, as Biden did after the decision in Trump v. U.S. He needs to help restore the balance.