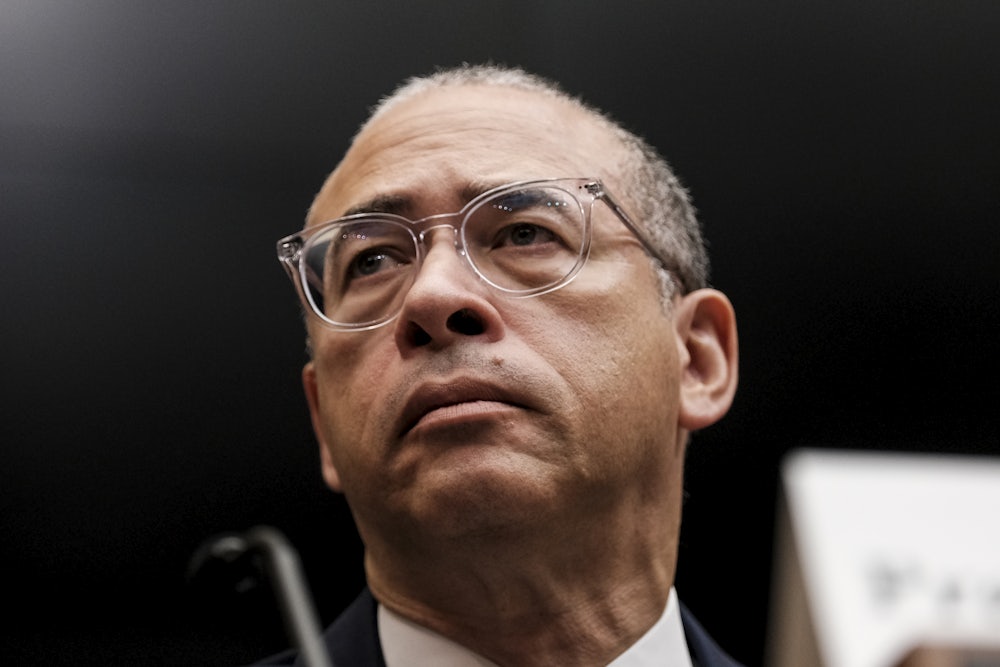

Almost every media account of Jonathan Holloway’s announcement this week that he’ll resign as president of Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey, adds that he is Rutgers’s “first Black president.” But Holloway’s race hasn’t figured at all in the toxic crosscurrents, coming from left and right, that have driven him to resign after finishing his first five-year term at the university. Race hasn’t figured in his own personal calculations, either, as I know from having spoken with him often during our years teaching at Yale, where he taught African American history; headed a residential college named for the infamous American advocate and architect of slavery John C. Calhoun; and then served as dean of the whole of Yale College before becoming the provost at Northwestern University and, in 2020, the president of Rutgers.

“[University presidents’] jobs are difficult in good times,” Holloway recently told the Newark Star-Ledger’s Tom Moran, “but when you’re facing absolutely no-win situations constantly, in this era of hyperbole about failing to do X, Y, and Z.… None of us signed up for that, just like I didn’t sign up to have a police detail with me everywhere I go.”

Let “X” designate a labor strike, last year, unprecedented in Rutgers’s history as a public university, by faculty and staff unions raising pressing concerns about pay, equity, and work rules but also prompting harassment of Holloway and his family at their home and elsewhere on campus. He sought an injunction against the strike because New Jersey law prohibits strikes by public employees, but Governor Phil Murphy intervened to settle matters less confrontationally, with significant increases in pay.

“Y” can represent the challenges posed by some pro-Palestine student protesters whom Holloway persuaded to dismantle their own campus encampments peacefully, but only after he made some concessions to their demands by agreeing to offer scholarships for Palestinian students displaced from Gaza and also by agreeing to look into disinvesting from the school’s scholarly exchanges and joint ventures with Israeli universities. He defended some such ventures on grounds of the academic freedoms of inquiry and exchange, but opportunistic congressional Republicans such as Virginia Foxx nevertheless attacked him frontally but falsely for fueling antisemitism. Let “Z” stand for Holloway’s initiation of a formal investigation of charges that a Rutgers gymnastics coach had engaged in bullying, favoritism, and revenge against athletes.

Irrelevant references to Holloway as the “first Black president” ignore the rich irony that his principled, “freedom first” approach transcends and transvalues racial approaches, as I explained at some length five years ago in a profile of him for Salon, written as he was facing controversy over proposals to rename Yale’s Calhoun College. Yale’s designation of Holloway as the college’s “master,” or head, was a tribute to his strengths not only as a historian credentialed to reinterpret the past but also as a leader of young people shaping the future.

Holloway at first resisted the clamor to rename the college because, as he explained, he preferred to make a “powerful statement about the redemptive power of the American experiment.… The very fact that Calhoun could not imagine someone like me teaching at Yale … offered a commentary on how far we had come as a country.”

That was no idle excuse. Holloway’s strengths owe a lot to his parents’ as well as his own way of rising above racism and racial politics without ignoring its realities. Born in 1967, Holloway had grown up in Montgomery, Alabama, and other places from which his Air Force father, the first Black instructor at the Air War College, flew frontline missions in Vietnam and other hot spots. When Jonathan was 6 years old, the Air Force decided to improve its public image by making his father a general in the Strategic Air Command. As the son reports in his book Jim Crow Wisdom: Memory and Identity in Black America Since 1940, a gripping memoir-cum-reckoning with race, Air Force higher-ups decided that the Holloways were “the right kind of family” to integrate both the Air Force and also the all-white Montgomery Academy that some military children attended.

Jonathan and his siblings became the first Black students to take that school’s admissions test, but when reports of the breakthrough enraged local racists, his father nixed the plan because he wasn’t a civil rights activist and didn’t want to head a “poster family” for integration. “Was his personal silence something that he felt he needed to pass on to his children?” Jonathan asks in his book. “Is that [silence] what made us the ‘right kind of family’?”

Whatever else it did signify, Holloway’s father had no liking for tokenism, or for merely breaking a structure’s glass ceiling without also changing its foundations and walls. He believed in bending history’s arc toward justice firmly without counterproductive histrionics. His son mastered the art of winning over presumptive enemies instead of demonizing and assailing them.

Small wonder that a year before the controversy over Calhoun College’s name erupted, I watched its “master” read from Jim Crow Wisdom to a rapt audience, while standing, with his characteristic dignity and friendly accessibility, next to his college’s mounted oil portrait of none other than John C. Calhoun. Sitting 10 feet away in the audience, ramrod straight and silent, was Holloway’s father, watching his son transvalue enough of Calhoun’s values to make Calhoun roll over in his grave.

Holloway told me years ago that he considers it less important to be “righteous” in a conflict than to find out where and how the other side may be right: “We are living in an era when nuance has lost so much value and when withering excoriations play better in a universe of likes and retweets,” he told The Yale Daily News in 2017.

Decorously enough, he’ll follow his resignation from Rutgers’s presidency with a sabbatical for academic research and a return to teach history there after that. Other universities may well recruit him, but it’s worth noting the statement by the chair of Rutgers’s own Board of Governors, Amy Towers: “Jonathan Holloway has led Rutgers with integrity, strong values, and a commitment to service and civility, while helping to steer the university through challenges facing higher education—including a global pandemic, shifting labor demands and a Supreme Court decision on Affirmative Action in admissions. Dr. Holloway’s decision was his and his alone; we respect it and thank Dr. Holloway for his passion and service.”

Adding credibility to Towers’s formal tribute, The New Brunswick Patch reports that “under Holloway’s leadership, the national reputation of all three Rutgers campuses also grew: Rutgers-New Brunswick is now ranked 15th best out of all public universities in America, according to U.S. News and World Report. Also, for the first time ever, Rutgers-Newark was named among the top 50 public universities and Rutgers-Camden was named among the top 100.”

Wherever Holloway’s trajectory takes him, we’d be right, and maybe even righteous enough, to deplore the histrionics of his critics and to follow his example.