“First come the gays, then the girls, then the industry.” Thus does Sex and the City’s Samantha, played by Kim Cattrall in radiant crimson, explain publicity to her muscle-bound boyfriend Smith Jerrod. At her urging, he has just cut an ad with Absolut Vodka, sprawled in bed, naked but for the bottle shielding his groin. He is having second thoughts, though, about the pornographic photo shoot, worried it might damage his credibility as an actor. But Samantha is proved prescient: First the gays take note of her Absolut hunk, then the girls, and soon he is filming movies on location.

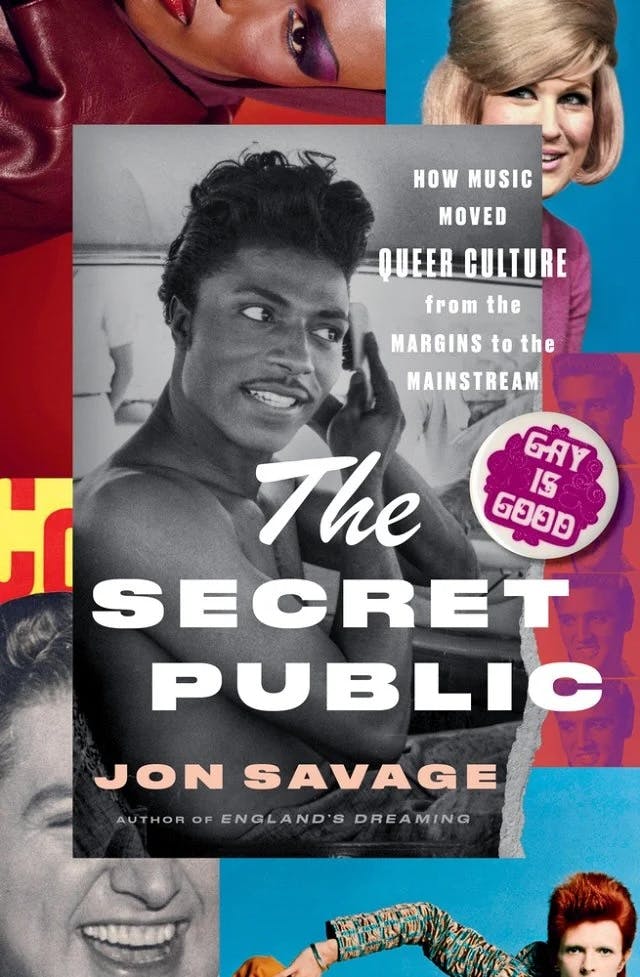

A silly moment in the show—and, ironically, the actor later sued Absolut. But the line is a fitting encapsulation of music historian Jon Savage’s argument in The Secret Public, a history of Anglo-American pop music’s hidden affinities with each country’s homosexual subculture. Encyclopedic in scope, the book is stuffed full of arcana about singers and songwriters, their managers, and the gay and lesbian venues they frequented. Their ties to the homosexual underground reveal that there was something undeniably queer about pop culture, and that music from rock to R&B to disco played a starring role in normalizing homosexuality on both sides of the Atlantic. Its appeal lay in the edginess of what had once been considered a deviant lifestyle.

There was something undeniably hip, Savage contends, about homosexuality: It was cool, it was glamorous, and, to put it bluntly, it sold. It’s a counterintuitive argument because we tend to imagine the decades after World War II as years of the closet, as a time before the queer subculture had come into its own and before it enjoyed any purchase on mainstream culture. But long before Troye Sivan made a name for himself as an unabashedly gay singer—before the United States and Great Britain decriminalized sodomy and even before the first gay liberation movements of the 1970s—queer subcultures shaped the beat of popular music in the postwar world.

On December 5, 1932, Richard Penniman was born the third of 12 children in Macon, Georgia. A Black boy in a racist country, he grew up singing gospel in and out of church. In the evenings, he worked at the local bus station, where he would see “people come in and trying to catch something—you know, have sex.” As a teenager, he fled home—his father beat his “half a son” regularly—and started singing with traveling bands. Adopting the name “Little Richard,” he recorded his breakout hit “Tutti Frutti” in 1955. The song, which sold 200,000 copies in a month, was an early sign of how the gay subculture had begun to interpolate itself within modern music. Its “breakthrough sound of freedom, couched in extreme androgyny” appealed to growing hordes of teen fans eager to listen.

That teenage economy is the linchpin of Savage’s book. In the 1950s, the number of young people began to grow year after year, as did their purchasing power, the economic swell of the postwar baby boom. With employment high and wages competitive, marketers began to turn their attention to what British pollster Mark Abrams termed “the teenage consumer.” In 1958, Abrams estimated, there were some six million Britons aged 16 to 25, with around 900 million pounds per year to spend at their discretion. Whatever—or whoever—could capture their imaginations stood to make a fortune.

The desires of the young, then, were the motor that powered the fluctuations in fads and fashions across the postwar decades. A series of musical styles came and went, from the rock and roll of the Beatles to the glam rock of David Bowie to the disco of Gloria Gaynor. While not all of these singers were queer, they were, as Savage highlights again and again, often managed by gay men who understood that their records were spinning in the gay bars of London and New York.

In the 1950s and 1960s, pop’s queer appeal remained unspoken, hidden by still-enforced sodomy laws on both sides of the Atlantic, a style that dared not speak its name. And many of the queer figures in Savage’s story met tragic ends. In 1967 alone, the year that Parliament decriminalized sexual acts between consenting men in the United Kingdom, the songwriter Joe Meek, playwright Joe Orton, and the Beatles’ manager Brian Epstein all died—either by their own hand or, in Orton’s case, murdered by his lover.

Amid burgeoning sexual liberation movements, the veil began to slip. The sexual experimentation that had long lurked just below the surface of modern music began to rise. In 1972, David Bowie declared to the music magazine Melody Maker, “I’m gay, and always have been.” Far from damaging his career, the admission only catapulted him to new heights of stardom. And as the queer charm of pop became ever more obvious, so too did the commercial outreach. By the 1970s, many record promoters were gay and lesbian: what “a lot of people on the scene,” according to Rolling Stone contributor Vince Aletti, called “homo promo.”

But it wasn’t until the takeoff of disco that queer music really came into its own. Characterized by syncopated beats that allowed dancers to lose themselves in the dance, disco “was the thing in the burgeoning gay clubs.” Bubbling up from underground dance scenes in the 1960s, it had become a dominant musical style by the mid-1970s, played at all of New York’s hottest clubs, from to the Tenth Floor in Chelsea to Studio 54 to the Ice Palace on Fire Island. Long before Lady Gaga released her gay anthem “Born This Way” in 2011, Alabama native Charles Valentino Harris made history in 1975 with what Savage terms “the first overt gay liberation disco,” fittingly titled “I Was Born This Way.”

Yet there’s an undeniable conundrum here. Why was pop culture so intertwined with queerness, when homosexuality was not merely stigmatized but illegal? These were the decades, after all, of the Lavender Scare, when gay men were one bad trick away from unemployment or prison. Why did this affinity between popular music and gay culture arise in the postwar years? And why did it endure for so long?

A version of Savage’s argument stretches back further. The artists of the Renaissance, to take one prominent example, were (in)famous for their homoerotic passions. Donatello was known to have had male lovers. In 1476, Leonardo da Vinci was accused—but acquitted—of sodomizing a model. And historians have long speculated that Michelangelo, with his heart-wrenching depictions of the male body, harbored a love for men. Of course, they were not unique—surviving court records suggest that a majority of Florentine men were picked up on sodomy charges at one point or another. Nonetheless, the association between homosexuality and artistic genius is an old one, and it has a Freudian explanation. Deprived of legal outlets for their passions, that argument goes, queer people are more likely to sublimate their desire into artistic pursuits.

Whether or not such arguments hold water is somewhat beside the point. Savage is right to point out that something changed in the postwar years. A new popular culture and a new queer subculture grew up in tandem, shaping each other in profound ways. There was something distinctly and recognizably queer about the sounds that emerged from the Cold War, just as burgeoning gay and lesbian subcultures followed musical fashions.

Part of the explanation undoubtedly lies in the structure of those subcultures. Historians of sexuality have long recognized that urbanization proliferates sexual identities, while also consolidating them. As a sexual orientation, homosexuality has existed since before the written word. But as a recognizable culture, one often associated with a certain gait, drinking certain beverages, frequenting certain locales, reading certain books, and speaking with a certain lisp, homosexuality is a modern invention. And it was in the metropolises of the twentieth century that this modern gay culture first took shape.

World War II accelerated the consolidation of these gay subcultures in American cities, as queer recruits met each other and settled down together in New York and D.C., Chicago and L.A. Distinctive gay styles cropped up in the ensuing decades, such as the instantly recognizable Castro Clone of San Francisco—aviator sunglasses, leather jacket over a hooded sweatshirt, and tight Levi’s with a colored hanky conspicuously draped out of one of its back pockets.

As these subcultures evolved increasingly ornate modes of self-recognition, homosexuality became not just a sexual preference but a lifestyle. And that lifestyle was increasingly delimited and therefore commodifiable. Magazines, sex shops, and clubs sprang up in major cities catering to queer people. These capitalist endeavors were, as the historian David Johnson has pointed out, important motors of the early gay rights movement in the United States.

In 1954, ONE: The Homosexual Magazine, published in Los Angeles, took the U.S. Postmaster General to court. He had declared the periodical obscene and therefore “unmailable” under the terms of the 1873 Comstock Act. Four years later, the Supreme Court sided with ONE. The burgeoning commercial subculture thus made possible a certain kind of consumerist (and consumable) homosexual, one who was generally white, male, and middle class.

Increasingly, then, queer activists would recognize the economy as a way not only to build community but also to act politically. As advertisers realized the power of the “pink pound,” queer people demanded that the companies they patronized support their politics. In 1973, for instance, queer San Franciscans boycotted Coors beer in solidarity with the local Teamsters union. In more recent years, though, this strategy has translated into the boardroom activism of lobbying giants like the Human Rights Campaign, a strategy roundly criticized by radical queer activists as narrowly focused on the needs of already-privileged gay men and lesbians.

Already in the 1970s, the middle-class queers served by this new subculture were the ones partying at Studio 54 or in Fire Island Pines, listening to Gaynor or Bowie. These were the kinds of venues where so much of the music Savage is interested in was, if not created, then at least sustained. In 1976, Newsweek published a cover story on disco that recognized “the group most responsible for keeping discos alive was the homosexual community.” Although the beat of the music had come from underground bars—many of them Black—and from African music imported across the ocean, it became commercially successful in the exclusive and overwhelmingly white halls of elite urban nightlife.

It was 1979 that “would see disco’s complete, albeit brief, conquest as a pop style,” Savage argues, as well as “a peak of gay visibility and acceptance.” Although The Secret Public ends here, in the frenetic beat of disco’s success—and before AIDS cast its shadow over American queer life—the phenomenon he describes was one with immense staying power. In the years and decades since, the bonds between pop culture and queerness have been woven ever tighter. Madonna’s “Vogue,” released in 1990 and still a hit, was inspired by the queer and trans ballroom scene in New York City. In the early 2000s, Lady Gaga, the queen of queer pop, got her start in gay clubs, much as Chappell Roan did years later. And let us not forget the greatest crossover sensation of them all, RuPaul Charles, who in 2012 protested, “I’m a marketing genius! I marketed subversive drag to ten million motherfuckers.”

But that’s just the problem. How subversive is it really when RuPaul’s Drag Race is watched by hundreds of thousands of viewers each week, has been franchised to over a dozen countries, and has won Emmy awards for eight years in a row? How edgy can voguing be, when popularized by a billionaire musician? What made homosexuality and its world attractive to the postwar culture industry was precisely its marginal position, its ability to see and hear differently from what was then considered normal. Queer men and women were persecuted outsiders—and that status on society’s margins was precisely what gave them a distinctive culture and could be defined, commodified, and marketed.

Today, the reality is different. Culture, like light from a distant star, tends to reveal the realities of a year, a decade, or sometimes even a generation ago. And so, despite a resurgence of homophobia and, especially, transphobia, despite bathroom bans and state-sponsored censorship, queerness remains a mainstay in the high culture of the U.S. As heat follows flame, so too queerness—or, at least, the kind of queerness that can be watched on Netflix or heard in clubs—has lost its edginess, its radical appeal. On the one hand, this ubiquity does reflect a certain acceptance of homosexuality, shown too in contemporary polls; that most are comfortable with gay people living their lives. But, on the other hand, it also hints that the more militant strands of the postwar sexual liberation movements, those who wanted to abolish the nuclear family or combat the commercialization of the queer subculture, have lost what cultural vitality they once claimed.

In October of last year, Canadian singer Shawn Mendes, whom many had long speculated was gay, told an audience in Denver, “The real truth about my life and my sexuality is that, man, I’m just figuring it out like everyone and I don’t really know sometimes.” It was a striking admission from a heartthrob musician who had long denied that he was—or even might be—gay. Yet, although horny men around the globe gleefully texted each other the good tidings, it was perhaps more significant that, to everyone else, the news was met with nothing more than a shrug.