Very little of what the film A Complete Unknown portrays is true to history, starting with the opening scenes. It opens with a 19-year-old Bob Dylan arriving by car in New York City and quickly finding his way to Greenwich Village, where a random bearded man in a bar tells him where he can find Woody Guthrie, as if Guthrie’s location were common knowledge in the Village. Woody is a patient at the Greystone Park Hospital in Morris Plains, New Jersey, which it turns out is a psychiatric hospital, even though what Woody is suffering from is Huntington’s disease. Dylan takes a taxi across the river to Morris Plains, 35 miles away, as if that were a feasible thing for a broke 19-year-old to do.

When Bob enters Woody’s room at the hospital, he finds the renowned folk singer Pete Seeger present. With Seeger’s encouragement, he sings an ode he has written, “Song to Woody,” which incorporates aspects of Woody’s song canon. Seeger, himself a purveyor of Woody’s songs, signals his approval, and Woody raps on his bedside table five times to signal his own. Seeger, realizing Bob has no place to go at that moment, invites him to spend the night at his and his wife Toshi’s home, where they overhear Bob singing lines from a tender ode to his high school girlfriend, “Girl From the North Country.” Message: Dylan is not a one-trick pony; he’s the real deal and should be taken under Seeger’s wing. With the backing of Seeger, the veritable leader of the folk revival then underway in Greenwich Village, Dylan’s career takes off virtually immediately.

Up to this point, there is barely a shred of truth in the story. Dylan discovered where Woody was from his 13-year-old son, Arlo, after he tracked down the family residence, and Pete Seeger was not in the room when Dylan visited him for the first time, or at any other time, as far as anyone knows. Dylan did not write “Song to Woody” until later; it was his first mature song. “Girl From the North Country,” too, was not written until later. New Yorker film critic Richard Brody put his finger on what is really going on with these elisions and evasions in his review of the film: “The principal maneuver, in these early scenes, is to emphasize the role of the veteran folksinger Pete Seeger (Edward Norton) in Bob’s first breakthroughs so that, when, in 1965, Bob ultimately adopts what Seeger has dismissively called ‘electrified instruments,’ the loss of his friendship registers all the more keenly as a price to be paid.”

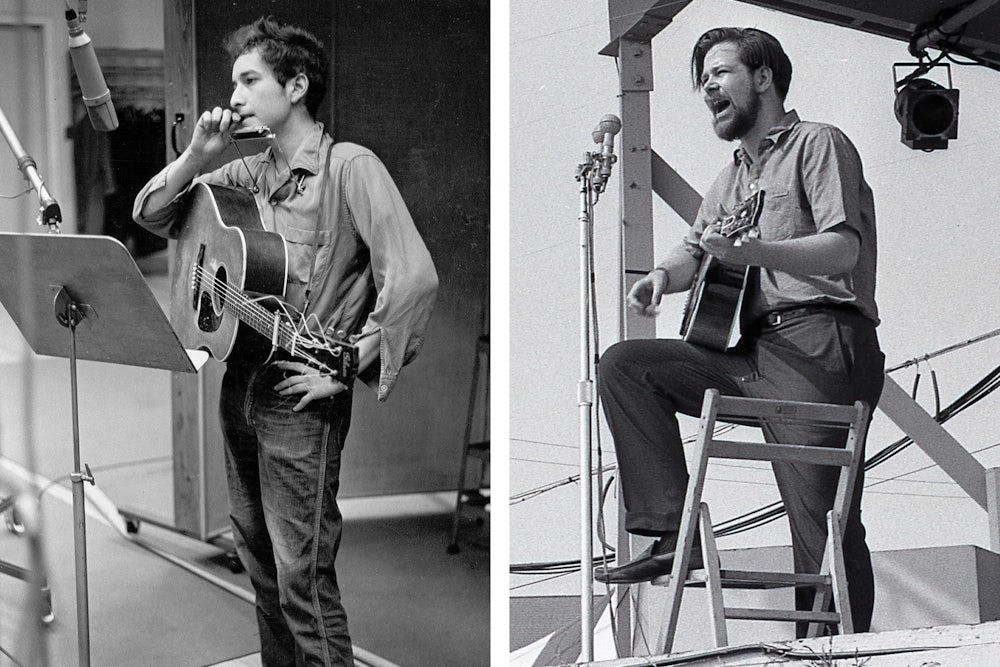

In fact, Dylan’s success, which, in retrospect, came relatively quickly, was not as assured as the film makes out. In Dave Van Ronk’s autobiographical memoir, The Mayor of MacDougal Street (edited and partly written after Van Ronk’s death by Elijah Wald, who also wrote the book Dylan Goes Electric, on which the film A Complete Unknown is partly based), Van Ronk says: “Looking back, what a lot of people don’t understand is that it was tough for Bobby at first. He was a new kid in town, and he had an especially abrasive voice, and no one had any way of knowing that he would eventually become BOB DYLAN—he was just a kid with an abrasive voice…. Bobby was doing guest sets wherever he could and backing people up on harmonica and suchlike, but there was no real work for him. He was cadging meals and sleeping on couches, pretty frequently mine.” It was Van Ronk, not Seeger, who piloted Dylan through the shoals of his initial career, but the film gives him virtually no credit. Yet the cover of one of the editions of Van Ronk’s memoir features the following quote from Dylan: “In Greenwich Village, Van Ronk was king of the streets, he reigned supreme.” (It is, however, probably better to be ignored completely than depicted as a lout and career failure, which is how the Coen brothers portrayed him in their 2013 film, Inside Llewyn Davis.)

Rolling Stone has performed the service of tabulating 27 different mis-directions in James Mangold’s film, some trivial, some more weighty. But after viewing it twice, and reflecting on its multiple discrepancies, I find myself doubting whether they really matter, given the overall trajectory of the work. They obviously haven’t mattered to Dylan, who reportedly recited the entirety of his parts in the script with the director. Clearly, he feels Mangold’s approach conveys the essence of that period of his career.

The story in brief: A young and callow Jewish kid from the freezing hinterlands of Minnesota comes to New York City to pursue a career in folk music, a form gaining in popularity among a segment of the public, but one unlikely to lead to fame and fortune. In less than a year, however, he is signed by the eminent Columbia Records. His first album, simply titled Bob Dylan, which contains only two songs written by him (“Song to Woody” and “Talkin’ New York”), bombs; but his second one, The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan, sells more than a million copies; and his next album, The Times They Are a-Changin’, establishes him as the musical voice of the then-burgeoning civil rights movement. What does it matter if the film mixes up the chronology and the settings of his various youthful, overlapping love affairs? What is most important is the movie’s finale, when Dylan shatters the Newport Folk Festival with ear-splitting electronic rock music.

But, dear readers, ponder this: In high school, before he gravitated to folk music, Bob Zimmerman was part of several teenage rock bands, and on one occasion sang a song so loudly in a school assembly that the principal cut the microphone. What were the lyrics to the song? They were: “ROCK AND ROLL IS HERE TO STAY, IT WILL NEVER DIE!”