To take on a subject that has been extensively written about requires a degree of both daring and ambition in an author. When I started to read The Many Lives of Anne Frank by Ruth Franklin, I thought there was little that I didn’t know about Anne and her circumstances. I had read her world-famous diary (eventually published in more than 75 translations), of course, and had tried to emulate it by starting my own diary. (This exercise lasted all of a week.) I had also visited the secret annex in Amsterdam at Prinsengracht 263 and been astonished by the restricted space, hidden by a bookcase, in which eight people had managed to conduct their daily lives for two years, from 1942 to 1944, in relative civility.

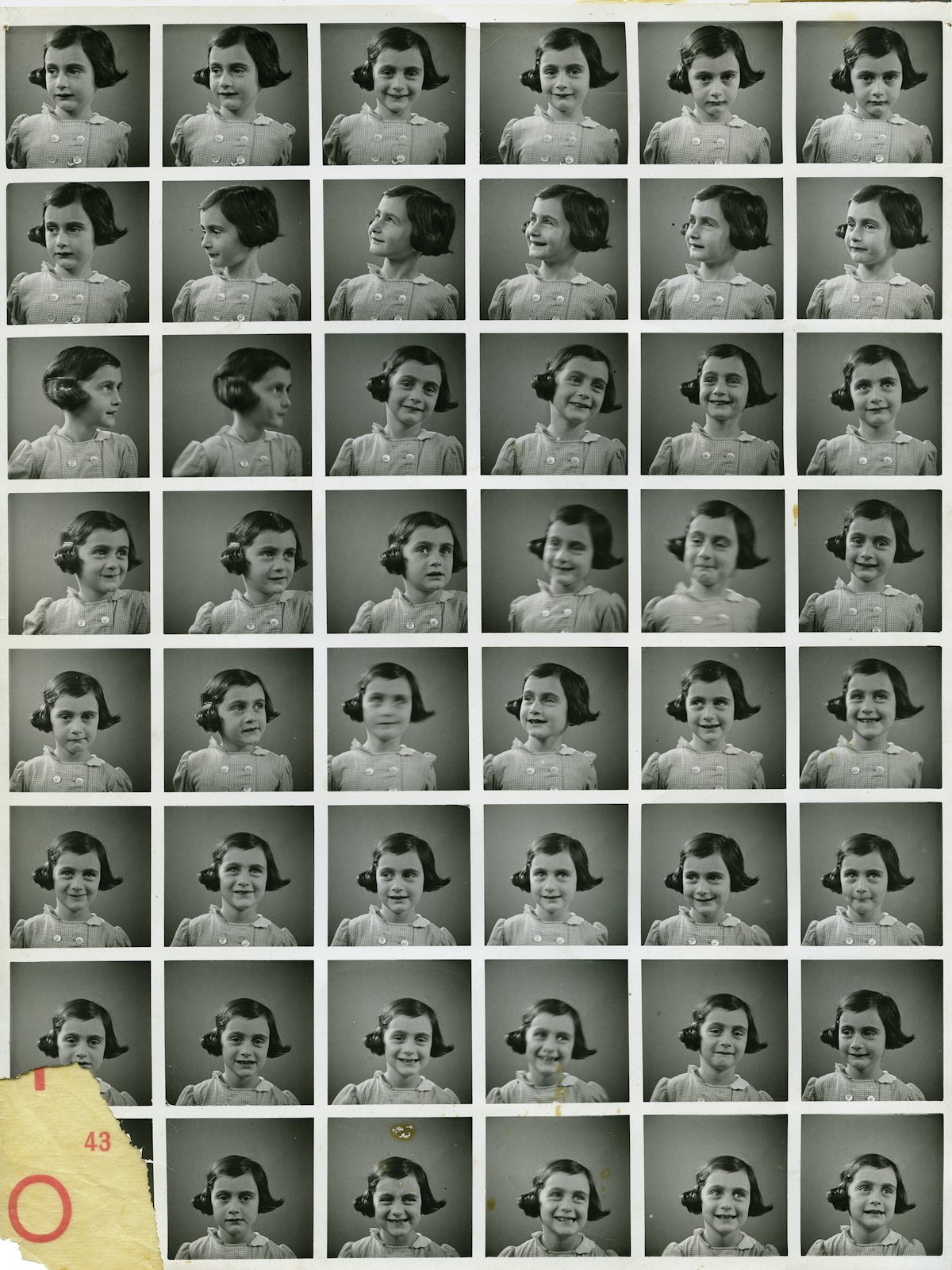

I knew that 13-year-old Anne, with her shiny dark hair, lively eyes, and beguiling smile, was spunky, with a romantic streak a mile long; that she and her older sister Margot were close; that she had negative feelings about her mother, Edith, while adoring her father, Otto. During my visit to the annex, I had been especially moved by the charming postcards—Franklin mentions one “with a photo of chimpanzees having a tea party”—and photos of movie stars like Greta Garbo and Ginger Rogers. She had also pasted pictures of the British royal family on the wall, as though she were for all the world living in a bedroom in Scarsdale that she could decorate as she pleased.

Her death from typhus in Bergen-Belsen the same month her sister succumbed, in the winter of 1945, after Auschwitz had already been closed down and within months of the end of the war, seemed almost implausible. I didn’t know if I completely bought into the idealized version of Anne as a beacon of hope for mankind—in the most famous line from her diary, she avows, “In spite of everything, I still believe that people are really good at heart”—but I warmed to her feistiness and found her acute in her perceptions of the other inhabitants of the annex and often wise beyond her years.

None of which is to say that I am an expert, but rather to suggest that being a Jewish girl from an observant background as I was, with German Jewish parents who had escaped Hitler, and with a burgeoning wish to myself become a writer, Anne was part of my consciousness growing up. It is all the more surprising, then, that Franklin has written a book that is gripping in its telling of a much-told story, adding nuances and details that weren’t known before. She focuses less on Anne as a person with a heartrending life than on what we, her readers, have made of that life: The idea of Anne Frank, Franklin writes, “has become a mirror of broader cultural and political preoccupations,” so that when we talk about “Anne Frank,” we’re not talking about a person as such, but about the constellation of ideas, based on our own experiences, that swirl around her image.

The transformation of Anne Frank “into an icon,” Franklin argues, “has had the effect of obscuring who she really was. She becomes whoever and whatever we need her to be.” The Many Lives of Anne Frank aims to convey a sense of the artistic growth of Anne as a serious writer and to show her diary as more than an incidental find that just happens to speak to many readers, but rather as a very specific creation, an artifact of her literary imagination as much as an immediate record of life in the annex.

Anne Frank’s comfortable, upper-middle-class childhood in Frankfurt before the Nazis came to power at the beginning of 1933 makes a striking contrast with the cloistered household described in her diary after her family went into hiding. The details of these years make clear the enormity of the change from an open and gregarious engagement with the “inhabited world,” as Anne once phrased it, to an immensely constricted perch. The Franks lived in a five-room duplex, decorated with antiques, green velvet curtains, and Persian rugs. Otto Frank ran Opekta, a spice business, and both he and his wife, whom he had married in middle age, were doting parents.

As the Nazi vise began to tighten around Europe, an influx of German Jews sought refuge in Amsterdam, including the Franks, who moved there in 1934, when Anne was four years old. In early May 1940, Hitler’s army invaded the Netherlands, and the Dutch surrendered within days. In April 1942, Jews were commanded to wear the yellow star, and in June, Adolf Eichmann ordered the first deportations of Dutch Jews to Auschwitz. After attempting unsuccessfully to arrange for emigration papers, Otto put together an ingenious plan to hide his family within Amsterdam. They would live on the third floor of the back section of the gabled eighteenth-century building, on a canal, where his business was housed. In preparation for the move, Otto and two associates had carted food, bedding, and furniture, including dining room chairs, to the annex, which had two levels connected by a “steep and rickety” staircase. He “even managed to bring Anne’s collection of film star photographs without her noticing,” Franklin notes.

At daybreak on Monday, July 6, 1942, the Franks moved to their new quarters, wearing all the clothes they could bring; Anne wore two undershirts, three pairs of underpants, a dress, skirt, wool cardigan, and a coat. Otto managed to protect his firm from “Aryanization” by transferring ownership of Opekta to two non-Jews, Victor Kugler, his second-in-command, and Jan Gies. Throughout the Franks’ time in the annex, the family depended on the unfailing kindness and assistance of Gies and his wife, Miep, as well as on Bep Voskuijl, another of Opekta’s employees. Miep shopped for them and visited daily, bringing news of the world outside; she and her husband even slept for a night in the annex. Eventually, four more people joined: In July, Hermann van Pels, his wife, Auguste, and their teenage son, Peter, moved in. In November, Miep’s dentist, Fritz Pfeffer, was added to the crew.

A German Jewish émigré in his early fifties, Pfeffer seems to have initially charmed Otto and Edith while annoying Anne. It didn’t help that she had to share her tiny bedroom with him or that they argued about how long Anne could write at the desk in their room. Pfeffer also shocked the other annex residents by revealing to them the truth, from which Miep had tried to shield them, about the fate of the transports leaving for Westerbork (a temporary collection point for Dutch Jews) and beyond. “The news about the Jews,” Anne wrote in her diary, “had not really penetrated through to us until now.… The stories he told us were so gruesome and dreadful that one can’t get them out of one’s mind.”

Franklin deftly evokes the texture of daily life in the annex, emphasizing the discipline that was required to keep things running smoothly. Wake-up was at 7, and breakfast at 9; there were scheduled slots for the bathroom. Specific times were set aside for reading the library books brought in every Saturday, and others were allotted for chores and the girls’ schoolwork. Anne started her diary in earnest in June 1942, having begun writing in a notebook with a red-checkered cover that she received for her thirteenth birthday. For the first few months, Anne wrote in it only sporadically, until in late September 1942, she decided to recast it as a correspondence, mostly with an invented friend she called “Kitty.” These initial writings would come to be known as Version A of the diary.

Anne edited her diary in 1944—according to Carol Gilligan’s account in her book The Birth of Pleasure, she began to rewrite it after hearing a broadcast from the Dutch government in exile about setting up a museum after the war, for which they were looking for diaries and letters. In Anne’s edited version (Version B) of her original diary, which was left unfinished, she changed the opening from the exultant “gorgeous photograph, isn’t it!!!” to a more formal, self-conscious beginning, with an eye for her prospective audience: “It’s an odd idea for someone like me to keep a diary.” Anne also edited out various sensitive or overtly sexual observations, such as “my vagina is getting wider,” and “Mummy and Margot and I are thick as thieves again. It’s really much better. I get into Margot’s bed now almost every evening.” She also wrote fiction, fables, and character sketches, trying her hand at different forms and honing her writerly craft. She even sought help in attempting to get her stories published, but it was considered too risky.

Anne turned 14 on June 12, 1943, having lived in hiding for almost a year. She had grown several inches; as a result, “she had to use chairs to extend her bed so that her feet wouldn’t dangle off at night.” Ski boots were the only shoes that fit her, and she had also gained 20 pounds, which left her bursting out of her clothes. Miep came to the rescue with a pair of secondhand red pumps: “She got very quiet then: she had never felt herself on high heels before,” Miep wrote in her 1987 memoir, Anne Frank Remembered. “She wobbled slightly, but with determination, chewing on her upper lip, she walked across the room and back, and then did it again.”

Anne began to feel a consuming interest in Peter van Pels, who was three years older than her, and whom she had initially dismissed as boring. Franklin’s approach to Anne’s growing awareness of and discomfort with her own sexuality and romantic longings is less routine and more psychologically informed than many other accounts, which treat it as a girlish crush. (One of the exceptions is Gilligan’s remarkable exploration of Anne’s emotional and sexual development in The Birth of Pleasure.) Anne wrote, “I made a special effort not to look at him too much, because whenever I did, he kept on looking too and then—yes, then—it gave me a lovely feeling inside.” Two months after they first connected, they sat together in Peter’s room (the smallest in the house), and he gave her what she regarded as her first kiss. In time, her infatuation cooled. “Maybe,” Franklin speculates, “like many adults as well as teenagers, she enjoyed the thrill of the chase (‘conquest’ is the word she uses) more than its satisfaction, with the corresponding decrease in excitement.”

The original manuscripts were discovered by Miep after the Gestapo raided the annex, on a tip, on August 4, 1944, and the Franks were sent to Westerbork. Otto, alone of his family, survived the war, weighing less than 115 pounds by the end of it. “Here is your daughter Anne’s legacy to you,” Miep told him when she gave him the notebooks and the loose pages, which had been scattered on the floor during the raid. “What Otto did with that legacy,” Franklin writes, “is perhaps the most confusing—and contested—aspect of Anne’s story.”

The ensuing tale is indeed a complicated one, featuring a large cast of characters and different agendas. For one thing, the pages presented both the Anne that Otto had known—“intelligent, creative, funny, impudent, independent-minded”—and aspects of her he hadn’t been aware of, including “her maturity, her capacity for self-criticism, her self-awareness … her love for nature or the consolation she found in her belief in God.” For another, he took it upon himself to shorten the diary by deleting or condensing entries or comments he found “too personal or offensive,” as Franklin puts it, an act for which he would be raked over the coals. Since Otto did not initially explain that he had worked from several versions of Anne’s diary, he was accused of having tinkered too much with his daughter’s legacy—of having cleaned it up, so to speak.

Franklin finds this criticism unfair: “It seems to me that the only real mistake Otto made in the process of preparing the diary for publication was not acknowledging the complicated genesis of the printed text.” In preparing a Version C of Anne’s diary for publication, Otto referred mostly to Version B, but also added selections from the original diaries (Version A) and from some of Anne’s stories. “She didn’t want things to be published,” he told Arthur Unger, a film and television critic for The Christian Science Monitor, in 1978. “Personal things, childish things which she saw as too childish. Sex things ... things like that are left out.” He deleted some of Anne’s harsher remarks about some of the annex residents, especially the van Pelses, and somewhat surprisingly, restored much of Anne and Peter’s romantic saga, which Anne had decided to leave out in Version B. (There would ultimately be a Version D, The Definitive Edition, which became the bestselling iteration in the United States, as well as an 851-page Critical Edition published by the Netherlands Institute for War Documentation in 1986, which included all the various materials.)

One might conjecture that Anne considered this partial love story somewhat hokey and too private for public consumption, while Otto, in turn, might have thought it would add to the diary’s universal appeal. (He seems to have been right about this.) Franklin approvingly invokes a critic, Philippe Lejeune, who pointed out that it was impossible to know what Anne might have intended. “Who knows but that two weeks later some pages might have been tossed in the waste-basket, or that some entries from the original diary left out by Anne might have found their way back in? Everything was still provisional and in flux.”

In her own account, Franklin moves back and forth between the versions, tracing Anne’s shift from a recorder of daily life and overheard gossip in the annex to a more meditative storyteller, concerned to make her diary stand on its own as a publishable text. “You can’t and mustn’t regard me as fourteen, for all these troubles have made me older,” Anne soberly reflects, becoming less the adolescent girl at the center of a tragic piece of history and more a self-possessed interpreter of her life and ordeal. The purely autobiographical impulse has given way to that of a writer creating a shapely, often lyrical narrative. “I wander from one room to another,” she writes, “downstairs and up again, feeling like a songbird who has had his wings clipped and who is hurling himself in utter darkness against the bars of his cage.” Franklin notes that “while the testimonial impulse is largely absent from the early days of Version A,” the revisions Anne made “to the entries for fall 1942 consistently offer more and clearer information about the persecution of the Jews as well as her commentary on it—essential to her new vision of her diary as a public document.”

As a result of Otto’s persistent efforts, the diary was first published in Dutch in 1947 in an edition of 1,500 copies. The German translation appeared in 1950, with further changes made by the translator, Anneliese Schütz, who later explained to Der Spiegel, “A book intended after all for sale in Germany … cannot abuse the Germans.” Anne’s description of Westerbork was deleted, and her line on “heroism in the war or against the Germans” was changed to “heroism in the war and the struggle against oppression.”

In the final section of the book, Franklin dives into the afterlife of the diary, as it became a vessel for other people’s projections and fantasies. A cult of celebrity, for instance, developed over her diary in Japan, where it has sold more than five million copies, perhaps because the Japanese saw their own destruction by the U.S. bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki as having a link to the Holocaust that ultimately killed Anne. It became as well a fulcrum for writers reimagining their own relationship to Jewish identity and mythology. A particularly fraught episode arose out of the adaptation of the diary into a Broadway play in 1955. The writer Meyer Levin read the diary in 1950 while living in Paris and had become obsessed with it. (He eventually wrote a memoir about his involvement with the diary called, in fact, The Obsession.) He wrote three articles for the New York Post about “what happened to the Annex residents after the diary ended” and put in a claim to write the Broadway adaption. His draft presented Anne as the “teller” of the great Jewish tragedy, Franklin explains, which in turn “made him unable to see her as anything else.” When the play’s producers rejected his script, a legal wrangle broke out, with Levin claiming his work had been deemed “too Jewish”; his memoir had already been rejected for publication.

“In retrospect,” Franklin observes, “many critics have concluded that for all his intemperance and megalomania, Levin was essentially right to represent Anne as more traditionally Jewish” than she ultimately was in the play, by Frances Goodrich and Albert Hackett, a married couple who had adapted It’s a Wonderful Life. Cynthia Ozick, in an essay in The New Yorker in 1997, took the playwrights to task for obscuring the story’s darkness and presenting a spectacle of “uplift and transcendence” (with a sunny Natalie Portman playing the lead). In the process, Ozick argued, they transformed Anne into a generic figurehead against prejudice. Or as the drama critic Frank Rich wrote in 1995, the downplaying of Anne’s Jewishness contributed to the “cultural defanging of Nazi genocide.”

Meanwhile, a new cohort of Jewish writers used the specter of Anne Frank as a way to take potshots at American Jewish identity. Whereas writers like Levin gave the trauma of the Holocaust a central place in postwar Jewish identity, writers like Philip Roth wanted to pull away from that framing, rejecting victimhood and embracing a deliberately pugnacious, often provocative Jewish masculinity. Roth made Anne Frank a character in The Ghost Writer (1979), bringing her back to life in the form of one Amy Bellette, the former student and mistress of the great but neglected writer E.I. Lonoff (based on Bernard Malamud), to whom the narrator, Nathan Zuckerman, has come to pay homage. Zuckerman is attracted to Bellette’s “severe dark beauty” and “fetching accent”; he begins to believe that she is Anne Frank, who has miraculously survived the Nazis. Ultimately, Roth’s version of Frank is of a collective mirage, pathetic rather than heroic, and conflicted about the very Jewishness she has come to symbolize.

Roth’s treatment was subtle compared to Shalom Auslander’s scabrous novel, Hope: A Tragedy (2012), in which an old woman claiming to be Anne Frank utters unlikely declarations like “Blow me” and “I’m sick of this Holocaust shit.” By this time, Anne had achieved full-fledged mythic status, a figure whose virginal purity was begging to be defiled by writers like Auslander, intent on casting aside Jewish pieties about the Holocaust and the nature of survival.

Finally, Franklin turns to the Palestinian-Israeli conflict and wonders whether Anne would have believed in the Zionist cause. “No one can know what political beliefs a surviving Anne would have held,” Franklin writes, having noted two paragraphs earlier that “while it’s possible to extrapolate a belief in the need for a Jewish homeland from Anne’s comments on Jewish identity—‘we can never become just Netherlanders or just English or any nation for that matter, we will always remain Jews’—she never made the connection explicitly.” Franklin appears to waver on where to locate Anne in this scorched political landscape, but one might argue that it’s too much of a stretch to bring her in at all. Anne was not particularly political, preferring movie magazines to newspapers. Trying to figure out how she would have reacted to political events she could never have anticipated seems a futile exercise.

While The Many Lives of Anne Frank is almost too exhaustively detailed, and at times disorganized, Franklin makes a young girl who has mutated into a cultural phenomenon come alive in her own mercurial right. In doing so, she deepens the tragedy of Anne’s end and renders her own book as much an act of devotion as of scholarship. In Anne’s introduction to Version B, she had written, “Neither I—nor for that matter anyone else—will be interested in the unbosomings of a thirteen-year-old schoolgirl.” How wrong she was.