One day in early fall 1930, a black car arrived at a small wood-frame house in Odanah, Wisconsin, to whisk 5-year-old Bernice Rabideaux and her four siblings away to St. Mary’s Catholic Indian Mission School. After the break-up of their parents’ marriage, the children, citizens of the Bad River Ojibwe tribe, had been living with their grandmother, but she could no longer afford to care for them. The Bad River reservation was one of the poorest in Wisconsin, and Bernice’s grandmother had to fall back on “the chilcare choice of last resort”—an Indian boarding school.

At the school, which was operated by the Sisters of Perpetual Adoration, Bernice lived in fear of pinches, slaps, and whipping from nuns, who regularly referred to her and the other students as “dirty Indians.” Her daily life was heavily regimented. After waking each morning at 5 a.m., she washed up at a communal sink, cleaned her teeth with a towel, and walked a quarter-mile to Mass. She and her siblings were fed corn mush and forced to work long hours in the laundry and garden. They were always hungry. Once, a nun beat Bernice for stealing an apple from the cellar. The few hours of daily education she and her siblings received were designed to “civilize” them and assimilate them into white Christian culture. Bernice lived at the school until she completed the eighth grade.

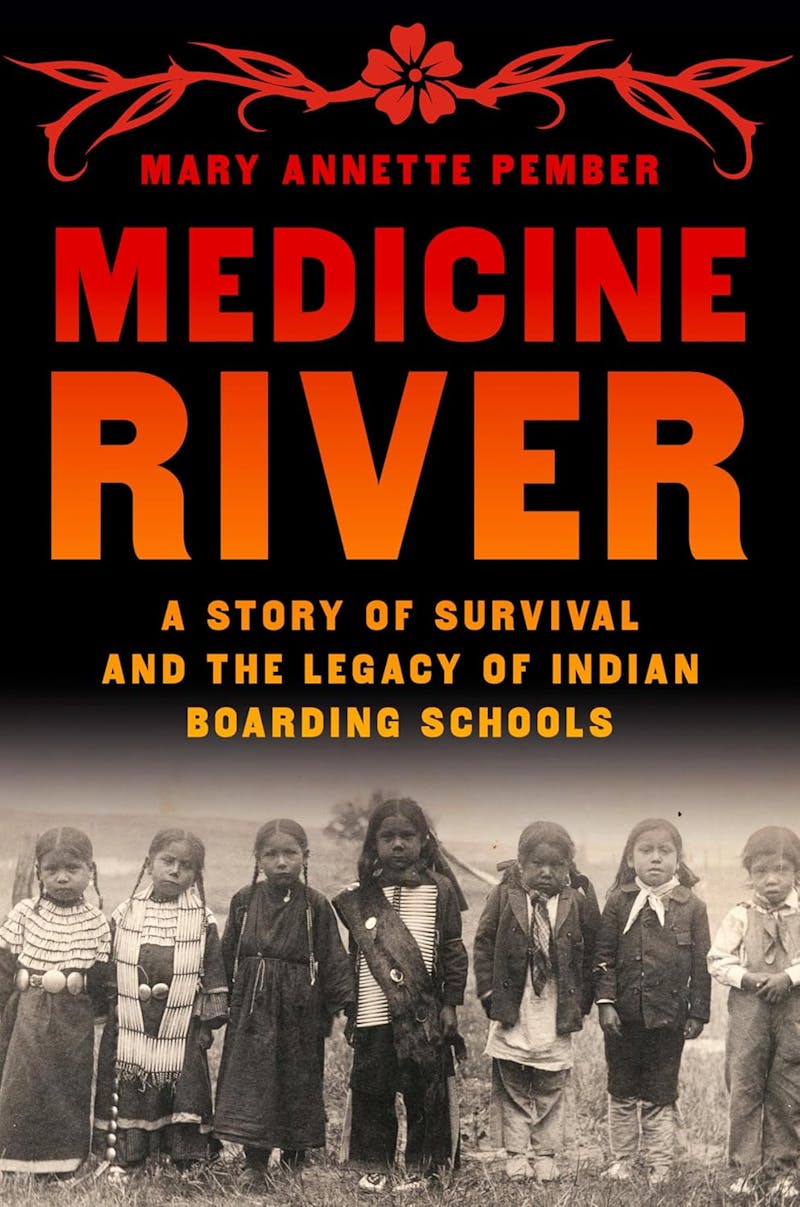

As her daughter, Mary Annette Pember, explores in Medicine River: A Story of Survival and the Legacy of Indian Boarding Schools, Bernice was just one of tens of thousands of Native children who were coerced to attend Indian boarding schools across the United States as part of a 150-year project of forcible assimilation. Most Native Americans alive now can trace a family connection to the system, which was funded by the federal government from 1819 to 1969; by the 1920s, a jaw-dropping 76 percent of Native children attended such schools.

Despite its scale and the impact it had on Native communities, the system was little known to the general public until 2021. That spring and summer, the discoveries of what appeared to be hundreds of unmarked graves at the sites of former Indian residential schools in Canada spurred a belated reckoning with the horrific history of such institutions on this side of the border. Canada had designed its residential school system after the U.S. system, wherein children were removed from their families and tribes and made to undergo forced assimilation that stripped them of their tribal languages, traditions, spiritual practices, and kinship connections. At boarding schools in both countries, Native children experienced rampant physical and sexual abuse, labored for long hours, and suffered from malnutrition and cramped conditions that facilitated the spread of disease. But while Canada completed, in 2015, a yearslong Truth and Reconciliation Commission process, with the aim of investigating and coming to terms with what happened at the residential schools, the United States has not yet launched a similar project.

The U.S. government took a belated first step toward such a reckoning in June 2021, after the discovery of the unmarked graves in Canada, when then–Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland, an enrolled member of the Laguna Pueblo whose grandparents were forced to attend Indian boarding schools, announced the creation of the Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative. The initiative was tasked with documenting the government’s operation and support of Indian boarding schools, tracing their “lasting consequences,” and investigating Native children’s deaths there. The resulting reports have made clear for the first time the scale of a scheme in which federally funded education was used to assimilate Native children with “systematic militarized and identity-alteration methodologies” at nearly 500 boarding schools across the country. In one of his last acts as president, Joe Biden issued a formal apology to Native peoples on behalf of the United States for our country’s role in running these boarding schools.

Pember, a citizen of the Red Cliff Band of Wisconsin Ojibwe, notes in Medicine River that many Americans learned of the devastating history of Indian boarding schools for the first time when widespread reporting of the unmarked graves in Canada roused public awareness. But for Native communities, the reality of these schools has always been impossible to brush aside. “For Indians, the most shocking element of the story was not the discovery of the graves,” she writes, “but the fact that it’s taken so long for non-Indians to acknowledge the grim details of this long-ignored history.” Pember has known of it since she was a girl growing up in the 1950s and 1960s. As her mother’s “secret confessor,” she often listened to fairy-tale-like stories of the horrors Bernice endured at the Sister School, as it was known, horrors that left Bernice with “angst, mysterious headaches, nameless fear, shame, cruelty, and hypervigilance,” all of which Pember was forced to navigate throughout her own childhood and adulthood.

A national correspondent for ICT News who has had a long career covering Native issues, Pember approaches Medicine River as “part journalistic research, part spiritual pilgrimage.” Throughout her life, Bernice, like many Indian boarding school survivors, was too traumatized to dissect what had happened to her. What motivates Pember’s project in Medicine River is a need to face what her mother could not. If she can understand what happened to Bernice at the Sister School—and to other Indian children at schools like it—she will be able, she hopes, to “move forward as an Indian woman in the world.” This quest threads throughout her archival research and reporting on the boarding school era and its long aftermath, making palpable the very personal costs of America’s attempts to acculturate Natives.

Despite the new levels of public consciousness around the existence of Indian boarding schools in the U.S. in recent years, the literature of this history has until now been largely relegated to the niche of academic presses. Pember’s accessible blend of the personal and the historical gives Medicine River the potential to further popularize this history. The book could not be more necessary or overdue, especially as we face yet another administration that refuses to reckon with the government’s role in the attempted destruction of Native culture.

Pember’s use of her mother’s experience at the Sister School provides readers a touchpoint for comprehending the effects and consequences of assimilationist education. The school was founded in 1883, in what Pember calls a “microcosm of what unfolded in much of Indian country during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.” During this period, tribes lost hundreds of millions of acres of land to exploitative treaties and legislation. An 1837 treaty with the U.S. government cost several bands of the Ojibwe 13 million acres of land in Wisconsin and Minnesota; an 1854 treaty further circumscribed the Ojibwe to reservations, like that in Bad River, where Pember’s family lived. “Bad River” is a settler term for the river that flows through this part of northern Wisconsin; the Ojibwe call it Mashkiiziibii, or Medicine River, because “it’s said that everything needed for mino-bimadizwin, a good life—food, medicine, and spirit—is available in its coffee-colored waters and along its banks,” Pember writes. The settlers’ misguided renaming of the river speaks to their wanton disregard for Native wisdom.

As the government expropriated land from Natives and relegated tribes to reservations where they could not rely on traditional hunting and gathering for subsistence, driving them into desperate poverty, it also employed education as a means of pushing Indian children to abandon traditional ways of life in favor of farming or industrial wage labor. The first federally run Indian boarding school, the Carlisle Indian Industrial School, was founded in 1879, on the site of former army barracks in Carlisle, Pennsylvania. Carlisle’s founder, Captain Richard Henry Pratt, had lobbied Congress to open an off-reservation boarding school at the barracks after directing a prison for Indians at Fort Marion in Florida, where he found that a combination of isolation and education in the English language were successful “civilizing” methods. “Assimilation and indoctrination into the ideals and values of white culture were clearly a means to destroy tribal sovereignty,” Pember writes. The ultimate goal was “to free up land for white settlement and exploitation.”

But as Pember points out, the federal government had been funding the assimilationist education of Native children long before the founding of Carlisle. In 1792, under President George Washington, the U.S. began a practice of funding the work of missionaries to “civilize, convert, and educate Indians.” The Indian Civilization Fund Act of 1819 later codified and expanded this policy, leading to a rise in the number of religious Indian boarding schools across the country; by 1877, there were 47. The Sister School on the Bad River reservation joined in this tradition.

While Pember’s meticulous recounting of this history can at times drag, when she pulls back from these recitations to draw connections to her mother’s experience, Medicine River sings. Bernice may not have been successfully assimilated at the Sister School, but she did learn to be ashamed of being Indian. That shame was fueled by fear and trauma, and fueled Bernice’s lifelong stubbornness and rage. “Her vengeance would be disproving all the prejudices the sisters held about Indians as lazy, dirty, and biologically inferior,” Pember reflects. “She started work on the outsized chip she forever carried on her shoulder, sometimes nearly collapsing under its weight.” Pember and her brothers were raised in the shadow of that chip on Bernice’s shoulder, struggling with her “harsh and baffling ways” and attempting to avoid the hidden triggers that set off anguished spells of hand flapping and head shaking.

Pember completes her exploration of her mother’s time at the Sister School and the history of Indian boarding schools within the first half of Medicine River. In the remainder of the book, she moves far beyond that history, without losing sight of how it continues to color the contemporary Native experience. In this, Medicine River stands out against typical historical accounts of the boarding school era, which tend to focus only on what happened between 1819 and 1969. By expanding the frame up to the contemporary moment, both by telling her own life story and by examining the efforts of boarding school survivors to demand accountability from the Catholic Church and the federal government, Pember illuminates how Native cultures have resisted and persisted through centuries of attempts to eradicate their people, and how their long-standing traditions and spiritual practices can light the path forward for healing from the ongoing traumas the schools wrought.

Native researchers, such as the social worker Maria Yellow Horse Brave Heart, explain these aftereffects using the theory of historical trauma. In the first phase, a population is subjected to a mass trauma by the dominant culture—for Native Americans, colonialism, wars, and cultural genocide. That population displays physical and psychological responses to the trauma, as Bernice did. Finally, the population that experienced the trauma passes their responses on to their progeny. The historical trauma theory makes sense of “the high rates of addiction, suicide, mental illness, sexual violence, and other ills among Indian peoples,” Pember writes. She now understands her mother’s anger, aloofness, and bitterness as trauma responses, and her own struggles with alcoholism as the only coping mechanism that she was given to handle the anger and fear she inherited.

More effective healing methods could be found in tribes’ cultural and spiritual practices. Pember writes poignantly of visiting the remote Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta in Alaska, where Yup’ik peoples have developed a program based on traditional teachings to rapidly respond to crises among a community with high rates of suicide, physical and sexual violence, and substance abuse. Organized around the medicine of kaholian (unconditional love and understanding), the program also promotes traditional Yup’ik practices, such as the open discussion of feelings with elders to address problems—a cultural ideal that developed from the fact that “in the unforgiving climate of the tundra, survival depends on cooperation, effective conflict resolution, and good mental and physical health,” Pember explains.

Pember herself has turned to Ojibwe traditions and ceremonies to seek healing. Since her mother’s death in 2011, she has visited relatives on the Bad River reservation to “grieve and understand their lost childhood days for them, something they were never permitted to do.” Medicine River itself at once stands as a moving witness to Pember’s family’s traumas and a rousing demand for accountability from the government and religious organizations that attempted to destroy her tribe.