On election night in 2024, Missouri voters became the first in the country to lift their state’s total abortion ban, with a ballot measure meant to enshrine in the state’s constitution the right to end a pregnancy. More than 1.5 million Missourians—motivated by the Supreme Court’s overturning of Roe v. Wade two years before, a ruling that had triggered the Missouri ban—fought back with their votes. (The ban allowed only a narrow exception for life-threatening emergencies.) Today, if you go online looking for information about how to get an abortion in the state, you will come across numerous stories announcing the victory and describing the return of abortion services: “Abortions Resume In Missouri”; “Inside KC Clinic For First Abortion Since End Of Missouri Ban”; “Planned Parenthood St. Louis Resumes Surgical Abortions”; “Abortion Returns To Columbia, Opening Access For Mid-Missouri For First Time Since 2018.” Abortion Action Missouri, one of the lead groups that had advanced the campaign for Amendment 3, as the measure was called, pinned a jubilant post to its Instagram: Missourians had “ended the abortion ban.”

For liberals, the win represented a rare triumph amid an otherwise catastrophic defeat. Reproductive rights advocates had worked tirelessly in a place where, even before Roe’s demise, abortion had long been under attack. Voters in a red state had rallied to defend their access. Here, it seemed, was a good-news story—desperately needed both to lift our spirits and to point the way forward politically—and one I was happy to tell.

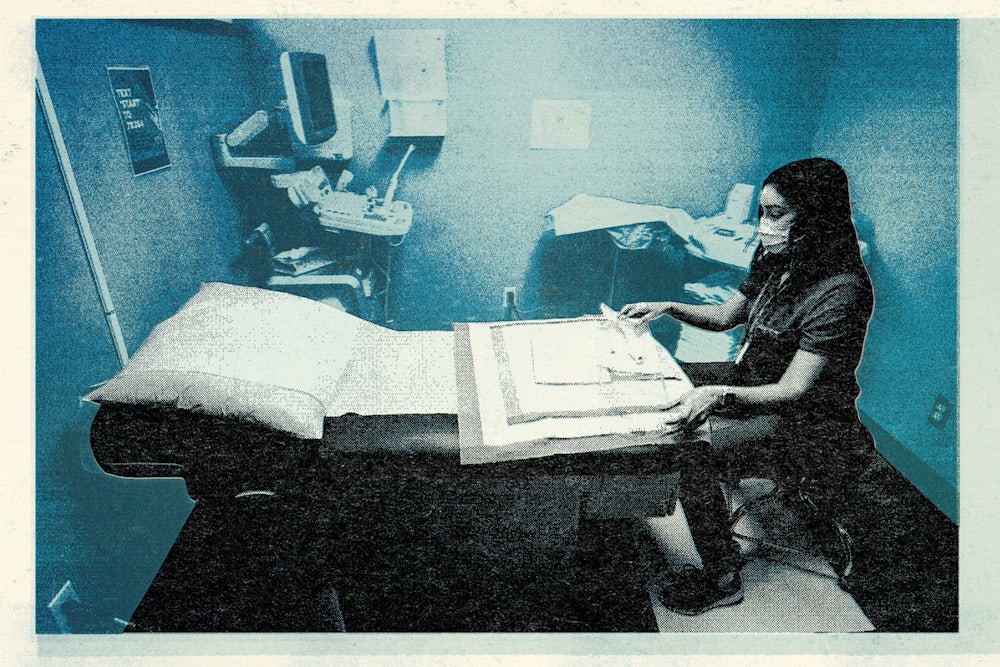

But the headlines, it soon became clear, had got ahead of themselves. Three Planned Parenthood clinics in Missouri have resumed providing at least some abortion care. But while courts had blocked the total ban, if you needed an abortion more than 13 weeks into your pregnancy, as of publication, those three clinics were not providing them. The same goes for medication abortion: Missourians have the right to end their pregnancies that way, but those clinics were not prescribing. Meanwhile, appointments for the limited procedural abortion care have been hard to come by. Only “a handful of procedural abortions” have been performed in the state, the Missouri Independent confirmed.

Organizations supporting abortion seekers in Missouri told me that virtually nobody is getting care in the state. Instead, they’re “going to Kansas, going to Illinois,” said Alison Dreith, the director of strategic partnerships at Midwest Access Coalition, a practical support organization that helps people cover expenses beyond the cost of the abortion itself. As of publication, Right By You, a free text line that offers abortion information and resources, had yet to hear from anyone in Missouri who was able to get an abortion in Missouri. On Right By You’s website, the first question on the FAQ reads, “Is abortion available in Missouri?” The one-word answer: “Maybe.”

Little more than five months since Amendment 3 took effect, it’s understandable that access to abortion is not yet fully restored; rebuilding after both a legal right and the infrastructure supporting it have been intentionally demolished isn’t easy. But over the course of my reporting, I spoke to more than a dozen advocates for abortion rights and reproductive freedom in Missouri, some of whom worked on the ballot measure campaign. They explain the limited access by pointing to weaknesses in the amendment itself.

Far from guaranteeing the right to abortion, these critics argue, Amendment 3 allows lawmakers to restrict access, just as they had before Dobbs, instead of confronting those restrictions head on. Most importantly, despite its name—the “Right to Reproductive Freedom Initiative”—the amendment allows for prohibitions on abortion after fetal viability, a legal limit drawn at the point a fetus is thought to be able to survive on its own, typically between 22 and 24 weeks. This is just one way that advocates say Amendment 3 reproduces the fatal flaws of Roe: It defines when the state can make decisions about abortion for pregnant people, an opportunity the state almost never refuses. If the abortion ballot measure was an undeniable win, it was also, according to advocates, a significant missed opportunity. It represented the capitulation of reproductive rights groups at a moment when they should have been asking for more.

For their parts, representatives from Missouri’s Planned Parenthood affiliates say they are moving as fast as they can, because the ballot measure didn’t automatically overturn the state’s myriad abortion restrictions; these had to be challenged separately. Many of the restrictions have been temporarily blocked, such as a 72-hour waiting period for patients and admitting-privilege requirements for physicians providing abortions. But others remain in place, including mandatory parental involvement laws and bans on insurance coverage for abortion. A legal fight over medication abortion is underway, and it is for now unavailable at Planned Parenthood clinics. The law, however, is not why some clinics were offering procedural abortion only up to 13 weeks. “We’re still training our internal staff,” Planned Parenthood Great Plains CEO Emily Wales explained. “Long-term,” she said, she anticipates her clinics “will go up to the legal limit.”

None of this surprises those who help Missourians find abortion care day in and day out. “It would be great if abortion could be returned within months,” said the director of Right By You, Stephanie Kraft Sheley. “I don’t see how that could possibly happen—because I am a lawyer, I understand how the courts move.” But voters don’t necessarily have the same understanding. Many of them, Kraft Sheley pointed out, were “under the impression that they were going to wake up after Election Day and abortion would be back.” Everywhere she turns, she said, she gets asked what’s going on. “People are very rightfully confused.”

What exactly Amendment 3 is meant to do is at the heart of multiple conflicts still surrounding the ballot measure. Anti-abortion groups claimed that it prohibited any regulation of abortion whatsoever and permitted ending a pregnancy at any stage. These charges were far from accurate, but they were given a significant platform by Missouri’s secretary of state, Jay Ashcroft, who fought in court to make the ballot summary presented to voters reflect these distortions. (He lost the fight.) Supporters of Amendment 3 meanwhile pointed out that the measure expressly stated the government “may enact laws that regulate the provision of abortion after fetal viability,” provided that those laws don’t restrict abortions needed to protect the life or health of the pregnant person. (The amendment defined “fetal viability” as the point at which “there is a significant likelihood of the fetus’s sustained survival outside the uterus without the application of extraordinary medical measures.”)

Writing fetal viability into the ballot measure did not mollify anti-abortion opponents. But it wasn’t meant to: Campaigners frequently said (and repeated to me) that including the viability threshold was necessary to win support for the measure from a majority of voters, including those who were uneasy about abortions later in pregnancy. However, Amendment 3 critics told me that this compromise—and others—coupled with the speed with which they were adopted, were exactly what has made the ballot measure so woefully inadequate.

To understand why the victory so disappointed these critics, you have to understand the position Missouri was in before Dobbs fell, a story that begins decades ago, with Roe v. Wade itself. While the landmark Supreme Court decision is often thought of as having guaranteed the right to abortion, it also established the state’s power to restrict it after viability, which it defined as the fetus’s capacity for “meaningful life outside the mother’s womb.” The justices were less interested in deciding when exactly viability begins than in establishing a standard for determining when the state should have control over pregnancy. Viability has remained an ideal vehicle for such interference ever since. In delineating when the government had “legitimate interests” in pregnancy, the court provided a path to control and criminalize pregnancy and its outcomes.

Roe sits uncomfortably as a “pro-choice” victory alongside the state’s many efforts at reproductive control and coercion, whether through forced sterilization of “unfit” parents, or through limiting welfare with “family caps” that denied benefits to parents who had more children after their eligibility was established. In that sense, viability functions as another form of reproductive control. Viability standards also contribute to inequality, removing options from people who are later in pregnancy, or making them available only at great expense and legal risk. Though it’s not often presented this way, a viability limit is another kind of abortion ban.

Further chipping away at this limited right to abortion was the Hyde Amendment, a provision first attached to congressional budgets in 1977, banning the use of federal funds for abortion provision (with very limited exceptions). As a result, abortion is not covered by Medicaid, except in some states that use their own funds to do so; an estimated 5.5 million women of reproductive age live in states where they can’t use their Medicaid coverage for abortion, according to an analysis by KFF, a nonprofit research group. Then Roe was weakened with the Supreme Court’s 1992 decision in Planned Parenthood v. Casey, which allowed lawmakers to restrict abortion in ways that would previously have been considered unconstitutional.

Casey decimated abortion access in Missouri, Roe’s putative protections notwithstanding. The number of providers in the state fell from 29 in 1982 to just one in 2019. That year, the state legislature passed a ban that outlawed abortion after eight weeks, before some people even know they’re pregnant; made no exception for rape or incest, only medical emergencies; and penalized providers with up to 15 years in prison. The bill also included a ticking time bomb: a total abortion ban that would be triggered by the demise of Roe.

Planned Parenthood in St. Louis challenged the eight-week ban and won a preliminary injunction, preventing it from going into effect. But state health authorities also weaponized the licensing process in an attempt to shut down the affiliate’s last clinic. At a hearing, the state health director admitted to using thousands of medical records obtained while investigating the clinic to create a surveillance spreadsheet, a document that included the dates of procedures, gestational age of fetuses, and estimated dates of the menstrual periods of dozens of patients. The message was: Abortion might still have been legal, but providers and patients would be made to feel as if they could be penalized at any moment.

Missouri had no independent clinics by this point, which is unusual nationwide; independent clinics provide the majority of abortions throughout the country, according to a report from the Abortion Care Network. The lack of diversity in providers was a sign of how decimated the landscape had become, said Amy Hagstrom Miller, the founder of the independent clinic group Whole Woman’s Health. “If you look at a state and you only have Planned Parenthood, it’s a sign that people don’t have as many options as they need.” Genuine access requires such options, she said. “It’s not abortion access if you can only get one kind of abortion on Tuesdays at 11 o’clock.”

Even when the St. Louis Planned Parenthood clinic prevailed in court in 2020, the victory was muted. Abortion had “essentially become a right in name only in Missouri,” said Yamelsie Rodríguez, then president and CEO of Planned Parenthood of the St. Louis Region, now called Planned Parenthood Great Rivers. Missourians had already been going out of state for abortion care; the clinic performed 2,532 abortions the year before its attempted closure, while 3,279 Missourians went to Kansas for their abortions. Now Missourians’ out-of-state abortions vastly outnumbered those provided in-state. In 2020, the St. Louis clinic performed 167 abortions; 3,200 Missourians traveled to Kansas, and 6,000 went to Illinois. The prospect of many more requirements could turn patients away, such as mandatory and medically unnecessary pelvic exams at least three days before (even though a pelvic exam would be performed immediately before the procedure). A pelvic exam was required even for medication abortions. Eventually, the clinic refused to provide these unnecessary exams—“because to do so,” its medical director said, “in my opinion, is just assault.” Then it stopped providing medication abortion altogether.

By the time Roe fell, in other words, Missourians had been going elsewhere for their abortions for years. Indeed, a majority of the patients supported by Missouri Abortion Fund had been visiting neighboring states since it was launched in 2016, said Jessica Lambrecht, the executive director. Of the roughly 6,600 patients it helped before Dobbs, more than half went to an independent clinic in Illinois, about 10 miles from St. Louis. Missourians in the Kansas City area were going to clinics in nearby Overland Park and Wichita, Kansas; those in St. Louis were going to Fairview Heights and Carbondale, Illinois. New independent clinics opened in Illinois, or significantly increased their staffing, for the express purpose of helping people traveling from states with bans. Illinois also had no laws requiring parental involvement, and its clinics provided care up to 26 weeks, which meant that young people and people getting later abortions found options there that Missouri lacked even before Dobbs.

When Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization overturned Roe in June 2022, Missourians did not have a lot left to lose. They may have felt—correctly—that a fundamental freedom had been stripped away. But in practice, Dobbs killed a right that in Missouri was more or less already dead. In the last six months before the decision, fewer than 100 people successfully got abortions in the state.

This troubling state of affairs may have been why some advocates in Missouri did not view Dobbs as a defeat. “There was a sense of opportunity and excitement with Dobbs,” said Bonyen Lee-Gilmore, who, when Roe fell, was the vice president of strategy and communications at what is now Planned Parenthood Great Rivers. “I know that sounds crazy…. But the opportunity was, we had a blank slate.”

Advocates in Michigan offered one path forward for the Missouri groups that wanted to seize the moment. Before Dobbs, they had launched a ballot initiative to amend the state’s constitution to assert, “Every individual has a fundamental right to reproductive freedom.” This was an expansive reframing of the right to abortion, which the measure included within “the right to make and effectuate decisions about all matters relating to pregnancy, including but not limited to prenatal care, childbirth, postpartum care, contraception, sterilization, abortion care, miscarriage management, and infertility care.”

The proposed amendment also prevented the state from penalizing, prosecuting, or otherwise taking any “adverse action against an individual based on their actual, potential, perceived, or alleged pregnancy outcomes, including but not limited to miscarriage, stillbirth, or abortion,” and protected people “aiding or assisting a pregnant individual in exercising their right to their reproductive freedom with their voluntary consent.” The Michigan reproductive freedom amendment did allow for the state to “regulate the provision of abortion care after fetal viability,” excluding instances when it would protect the life, physical, or mental health of the pregnant person, but the language had been developed before Dobbs, when viability, as enshrined in Roe, was still the standard. Some Missouri advocates wanted to be more ambitious.

On a Sunday morning in October 2022, with the November midterms just around the corner, Representative Cori Bush brought Missouri Democrats’ “Reproductive Freedom Tour” to Kansas City. The Dobbs decision had unleashed rage and energy across the country, and Democrats hoped to harness it. At the rally, Bush shared her abortion story; local elected officials spoke; and Justice Gatson, the executive director of the Reale Justice Network, announced a reproductive justice ballot initiative her group had in the works in Missouri. In addition to establishing “rights to bodily autonomy, medical privacy and equitable and accessible health care,” The Kansas City Star reported, “the ballot initiative would also protect health care for trans people and push for housing and bail initiatives.” It was expansive, and it spoke to the moment: Dems may have branded the event “Roe the Vote,” but Roe was in the rearview.

Gatson refers to herself as a social justice doula, and Reale Justice Network is a community organizing group in Kansas City that does work that has been historically overlooked in reproductive rights. “Most of us are birth workers,” she told me. “So we have that unique relationship with our community, one of a real position of trust.” Since its founding in 2009 to provide community among survivors of violence, the group has pushed for an end to the shackling of pregnant people in prisons and jails and led community “know your rights” trainings. For four years, Gatson was the Kansas City organizer with the ACLU of Missouri, where she was working when the trigger ban had passed. She saw the need for something new.

The ballot initiative Gatson announced at the Kansas City rally was known as Repro 4 MO. From the press coverage, the measure sounded more progressive than any proposed yet. It was also a coalition effort, along with MO KAN BIPOC Reproductive Justice Coalition.

Then working at Planned Parenthood’s affiliate in St. Louis, Bonyen Lee-Gilmore was also at the rally. “Truly, our world opened up,” she told me. “We saw the opportunity to sort of rebuild this from the ground up, in a way that centered patient care and unapologetically fought for rights and freedoms for all people.” All the obstacles thrown up over the decades by the anti-abortion movement were fair game now. “We wanted Hyde gone, we wanted insurance bans gone,” Lee-Gilmore said. “We wanted all restrictions gone, and we wanted young people to be able to access care.”

In November 2022, only a few months after Dobbs, Michigan’s reproductive freedom amendment won with 56 percent of the vote. The victory “set off sort of a domino effect,” Lee-Gilmore said, across “many, many states, of others wanting to do it, too.”

When she was invited to join discussions about a possible ballot measure, recalled Pamela Merritt, “Missouri had basically lost it all.” Merritt is a veteran reproductive justice advocate who grew up in the St. Louis area and worked for more than four years, including as a statewide organizer, with Planned Parenthood in Missouri. She is now the executive director of Medical Students for Choice, supporting a network of thousands of future abortion providers, but when she first joined the ballot measure discussions, she was representing Reproaction, a “left-flank” reproductive justice group that she had co-founded and co-directed. Merritt entered the discussions of what became Amendment 3 “in good faith,” she told me. Reproaction’s mission was to push both the left and the mainstream reproductive rights groups on reproductive justice—to urge them to stop being on the defense when it came to abortion and stop apologizing for care that had been deemed controversial even among reproductive rights groups, like later abortion and self-managed abortion.

Merritt was one of the only Black women at a majority white-led table, which also included the ACLU of Missouri, Abortion Action Missouri, and both regional Planned Parenthood affiliates (now known as Great Plains and Great Rivers). Merritt’s primary purpose for being there, she told me, was to ensure that the voices of Black Missourians were “part of the discussion.” She also wanted to encourage the emerging coalition to be more ambitious, to center those facing the most reproductive oppression, such as Black women, whose pregnancy-related deaths occur at three times the rate of white women in the state. Later, when Merritt heard about Justice Gatson’s ballot initiative, she suggested to Mallory Schwarz, the executive director of Abortion Action Missouri (formerly NARAL Pro-Choice Missouri), that they bring Gatson into the discussions, too.

Everything felt like it was happening at once, Merritt told me: Dobbs, Michigan, and Ohio was going to be next. Conversations that had felt exploratory before 2022 were now moving fast. A national group outside the abortion rights movement, the Fairness Project, which backs state ballot measure campaigns, took notice, and declared that it could see “the path forward for protecting access to abortion care through ballot measures.” With the nonprofit’s attention came millions of dollars to fund campaigns, flooding into states that had never seen that kind of money for abortion. The organization backed many of the ballot measure campaigns that were getting underway alongside Missouri—in Arizona, Florida, Montana, and Nebraska—all of which borrowed the Michigan measure’s language, mirroring Roe.

Lee-Gilmore joined discussions in 2022, representing Planned Parenthood St. Louis’s leadership team. Her aim, she said, was to remind people, “We don’t have to follow the Roe framework.” The position of the St. Louis affiliate, as laid out in a February 2023 memo, was clear: “The Roe framework and any legislative, policy, or political interference in reproductive health care including abortion will not get our support.” The clinic specifically cited viability limits, parental involvement mandates, and attempts to define exceptions for medical emergencies. It pointed out that the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists also “strongly discourages” the inclusion of viability in legislation.

“Good intentions to restore abortion access,” the memo cautioned, “can actually cause real and lasting harm, and will set us back.”

“Viability is not going to move a needle,” Merritt explained. “Most people don’t know what that is, and if anything, it hurts you.” The campaign never publicized its polling, but a number of post-Dobbs polls available in 2023, such as Gallup’s, showed increasing support for abortion without gestational limits. A 2023 survey by PerryUndem saw that a viability limit may actually “dampen strong support” for a ballot measure. Poll respondents said they worried that “politicians could outlaw most abortions by redefining viability,” that the language around viability was “vague,” and that “the state should not be involved.”

In March 2023, when Merritt saw the draft amendment language that the campaign intended to poll, it was still an open question whether it would include viability. But there were other problems: One version stated that nothing in the amendment would require government funding for abortion. The stipulation recalled the pathologization of Black mothers as “welfare queens,” a dog whistle used to stoke opposition to public assistance programs. “Coalitions give lip service to reproductive justice,” said Merritt, “but when push comes to shove, they dust off racist tropes.” The coalition also wanted to poll language that “the ballot measure wouldn’t interfere with parental rights,” as Merritt described it. “Which makes me sick.” Anti-abortion conservatives had long appealed to hostility toward the “undeserving” poor and panic about teen sexuality to turn people against abortion rights.

Around the same time, Kraft Sheley of Right By You heard from Mallory Schwarz at Abortion Action Missouri. Kraft Sheley had not been invited to join the coalition, she said, but Schwarz told her that they were considering multiple versions of the measure. “Some would explicitly carve out youth—and it would be explicit that parental involvement laws would remain intact,” Kraft Sheley recalled from their conversation. Schwarz had wanted to warn her, in case she saw it reported in the media, as well as reassure her: The coalition didn’t intend to use that language, Schwarz told her, but nonetheless “had to test” it. Right By You had begun as a resource for young people navigating the state’s mandatory parental involvement laws, which require proof of consent from at least one parent or legal guardian and proof of having notified the other. “I told her that under no circumstances would Right By You support a measure that carved out youth,” Kraft Sheley told me.

Despite her organization not having been invited to the table, in July 2023, Gatson met with members of the ballot-measure campaign. Reale Justice Network was survivor-centered, Gatson explained, and the measure was selling out young people. “There is no way” her group could support the measure, she said. “We have young people who are harmed in their homes.”

“I got an abortion, after a sexual assault, when I was 15,” Gatson told me. “Right here, at the local clinic. That can’t happen today for a 15-year-old who might need medical care in that way. That is something to mourn.... That is something that that campaign gave wrapped in a bow to, I would say, our enemies.”

The campaign ultimately filed 11 different versions of the “Right to Reproductive Freedom Initiative” with the Missouri secretary of state in March 2023. Some included the language about government funding, and some had language about mandatory parental notification for minors.

Some versions of the ballot measure included limits that were functionally gestational bans. In those, the measure’s definition of “reproductive freedom” excluded abortion after “fetal viability” and “after 24 weeks of gestation.” Only one version included none of the restrictions and exclusions found in the others. The coalition’s argument, Merritt said, was that they “have to draft this in a way that can win in a state like Missouri,” and that “something was better than nothing.”

Schwarz, in an interview this March, insisted that Amendment 3 was “not a re-creation of Roe” and that the media and “members of our opposition” who say that it is “are spreading misinformation.” Tori Schafer, the director of policy and campaigns at the ACLU of Missouri, who represented the organization in the campaign for Amendment 3, agreed that the charge that it reproduced Roe was “just not legally accurate.” She characterized Amendment 3 as having stronger protections, pointing to the restraints it puts on the government’s ability to restrict abortion. As with Roe, restrictions must be “narrowly tailored” to meet government interests without infringing on individual rights, as determined by the courts. Unlike Roe, the amendment stipulates that restrictions may not “infringe” on any person’s “autonomous decision-making,” and that the government may not “deny, interfere with, delay, or otherwise restrict” abortion. This language mirrors that in the 2023 Michigan amendment, which “simply restores the same protections … under Roe v. Wade,” one of its spokespeople said. Both these amendments (and many others) are a return to Roe’s standard of fetal viability. The idea that Michigan’s amendment was a return to Roe was a selling point, yet the Roe framing is one the Missouri campaign contests.

When Merritt raised her concerns with others on the campaign, she told me, they did not take them seriously. And when I asked Schafer about whether a more expansive measure was ever on the table, or if she had considered waiting for one, she implied that it would be too politically risky. If Missouri were to go another decade without abortion access, she said, “not only would that be politically harmful,” it would be harmful to Missourians.

But Merritt was thinking about the state of abortion access in Missouri had Amendment 3 not been on the ballot. In her view, talk of “something is better than nothing” can do serious harm. Missouri residents could travel to Illinois and Kansas, which wasn’t great but was access to more than nothing. As the coalition was debating the ballot measure, out-of-state clinics were serving several thousand Missourians each year; they will continue to do so until meaningful access returns to the state. The access the ballot measure could restore would primarily be close to existing clinics just over state lines, according to Merritt. People living mid-state, far from those clinics, would potentially benefit, she said. But was that worth the tens of millions of dollars the campaign was spending? Was it not also harmful to accept such a compromised amendment to restore such limited access?

Merritt notified the coalition that she was stepping down in July 2023, once it became clear that the measure was moving ahead despite her concerns. She felt pressured to “stand down,” as she put it, and keep her criticisms to herself. “It’s not the first time I’ve had powerful, well-financed, white political people tell me that,” she reflected. “But it is the first time I’ve had them tell me that after sitting up there screaming for 10 years that ‘Roe is the floor’ and that we need to ‘trust Black women.’”

By then, Lee-Gilmore had left the table, too. “If you’re measuring your success by the amount of money you can raise, OK, I’ll give you that,” she said. “But if you’re measuring success by how safe pregnant people are, I would say we have monumentally failed.”

“At some point when we were yelling at each other,” recalled Merritt, of a dispute with Schwarz, Schwarz said something like, “You know that I want abortion access for everybody” and “We want the same things.” “I had to say to her, ‘No, we don’t.’ You can’t say that you want the same thing and enshrine in the constitution the denial of that right.” (Schwarz did not respond to my questions about her conversations with Kraft Sheley, Gatson, and Merritt.)

There are “tensions” in every coalition they work with, insisted Kelly Hall, the executive director of the Fairness Project. When it came to which ballot measure might best restore abortion access, she said, the Fairness Project looked to its partners. “We are not reproductive rights policy experts at the Fairness Project,” she said. “We do not have a policy advocacy position.”

Merritt wanted to be clear that she was critiquing the campaign with 2026 in mind. It’s important to “discuss what went right and what went wrong,” she said, because there will be another raft of ballot measures that have the support of the Fairness Project and local partners, and in the discussions about how to craft them, Amendment 3 will be counted “as a victory.” Future campaigners may be uncomfortable confronting disagreements, or asking tough questions about which people will have access. But at the end of the day, she said, “the only reason abortion was an issue electorally in 2024 was because people didn’t have access to care. And half solving it for a majority of suburban white women doesn’t fix the situation at all.”

How can it be that the bold new solution to what Dobbs took away now risks repeating what was wrong with Roe—instituting a right that is not a reality? There remains a lot of confusion in Missouri, including among Amendment 3 supporters, Lee-Gilmore told me. “They did all this, and there’s no real access.”

Some of the people who walked away from the Amendment 3 coalition have come back together to, as they put it, “close all gaps that put Missourians who face the most barriers to abortion at risk.” This new group, called What’s Next, was founded by Justice Gatson, Stephanie Kraft Sheley, Pamela Merritt, Bonyen Lee-Gilmore, Julie Lynn, and Vanessa Wellbery. Like Lee-Gilmore, Lynn and Wellbery worked at Planned Parenthood Great Rivers; all three quit over Amendment 3. (While the affiliate had taken a public position against viability limits, parental involvement, and other restrictions, it ultimately backed the ballot measure.)

Because the measure did not automatically repeal the state’s anti-abortion laws, some restrictions remain, including those that Planned Parenthood and the ACLU have not challenged. The ban on insurance covering abortion means the right to abortion in Missouri applies only to those who have enough income or access to wealth to be able to afford the procedure. The restrictions mandating parental involvement for minors make the right to abortion applicable only to those young people who can comply; in late April, Right By You filed challenges to the parental involvement mandate and to a ban on helping minors access abortion. The organization has nothing near the resources of Planned Parenthood or the ACLU, which did nothing to challenge these restrictions. Considerable money had gone into Amendment 3, the members of What’s Next noted, while clinics nationwide are still “days away from closing and abortion funds are crowdsourcing funding for one patient at a time.”

The funds are still waiting to observe the practical impact of Amendment 3. Will people still support the funds after they have been told that abortion is back in Missouri? The Amendment 3 campaign spent more than $30 million, most of it in 2024. Planned Parenthood’s political and advocacy arms pledged to spend $40 million in 2024 nationwide. Meanwhile, Jessica Lambrecht, Missouri Abortion Fund’s executive director, told me that her group is currently able to contribute about a million dollars each year to cover the costs of abortion care, through block grants to the group’s clinic partners. The fund knows the need is greater. A single ballot measure campaign could pay for many thousands of abortions.

“I think it is easy for folks to get excited when they feel like they can participate in something such as a policy change or a legal battle,” Lambrecht reflected. “And that’s really important. But the value of an abortion fund is we are providing that direct and immediate need in real time ... because patients can’t wait for those changes to happen.” Through no fault of their own, patients may not even know what’s changed, she said, because there is so much misinformation around. “We should never assume that because a policy or a legal change has happened overnight that everyone understands that in application.” The fund can help with that public education, she said, but its clinic partners, including the Planned Parenthood affiliates serving Missourians, would have to take the lead.

No one I spoke to anticipated that independent clinics would return to Missouri anytime soon. Amy Hagstrom Miller, the founder of Whole Woman’s Health, told me that, after her successful challenge to HB 2, the Texas law that had shuttered her clinic, only a handful of the 40 clinics that had provided abortions before HB 2 were able to reopen. The resources and the infrastructure were simply gone.

Funding for actual abortion provision might still be the smallest fraction of philanthropic support for reproductive rights; the most recent figures from the National Committee for Responsive Philanthropy, from between 2015 and 2019, show that philanthropic support for abortion funds made up less than 3 percent of the $1.7 billion in foundation giving for reproductive rights. Even if abortion rights prevail in the courts, or through ballot measures, or some other long-game strategy, Hagstrom Miller fears that “you’re not going to have any clinics in the places where people need access to care.” Imagine if the same investment that has gone into the ballot measure campaigns was followed by a commensurate investment in restoring and expanding access to abortion. Or maybe, as Lee-Gilmore suggested, funders could say, “We’re no longer funding Roe strategies.”

In late March, I was outside Kansas City, visiting extended family. I had been hoping to go to a Planned Parenthood clinic there where abortion services were currently available, so I tried to make plans with the CEO of Planned Parenthood Great Plains, the affiliate that covers Missouri and Kansas. A communications staff member followed up with me. She wanted to make clear that none of the health centers in Kansas City “on the Missouri side” were providing abortion care the days that I would be there. “You still interested in visiting one?”

A week later, I spoke with the CEO, Emily Wales, by phone. Planned Parenthood had by then provided abortion care to at least one patient in three of its clinics in Missouri. The affiliate was focused on Columbia, Wales said, because that was where there was the most patient demand. Medication abortion remained unavailable at its clinics, owing to multiple legal challenges from the state attorney general (who had sent the affiliate a cease-and-desist letter for medication abortion, a service it was not providing) and the Department of Health and Senior Services (which Wales said effectively blocked them from providing medication abortion).

After speaking with Wales, I tried to book an appointment at the Columbia clinic, where, she said, “almost everybody” was able to get one. But there were none online, and there were none when I called. The receptionist suggested I go to Kansas.

I had one last idea. I remembered hearing of an ob-gyn in the area who had campaigned for Amendment 3 and belonged to a women’s health practice. You could see her in a campaign Instagram video saying, “Abortion is essential health care.” Maybe she was offering abortions. But when I called her office, the woman who answered the phone told me that the doctor did not provide “that service.” No one in the health center where she worked did, she added. She said I would need to call Planned Parenthood.