Earlier this week, the Department of Energy announced that it was clawing back $3.7 billion that its Office of Clean Energy Demonstrations had awarded, during Joe Biden’s administration, to 24 projects. The funds were rescinded, according to the department, after “a thorough and individualized financial review.” On its own, this news isn’t all that remarkable. The Trump administration has been axing climate programs for months, and $3.7 billion is relatively small potatoes compared to the thorough gutting of Biden’s signature achievement, the Inflation Reduction Act, that Republicans are queuing up in their budget bill.

Some of the biggest awards being cut, however, are for a technology that’s won the support not merely of Biden administration officials but of fossil fuel executives and congressional Republicans too. Carbon capture storage and sequestration, or CCS, uses specialized equipment to remove carbon dioxide from industrial processes, to be either stored indefinitely or utilized for some other purpose, like carbonating soft drinks or getting more oil out of wells. Among climate advocates, carbon capture has been the subject of fierce debate; many of them see it as a way for polluters to carry on with business as usual by promising to someday suck the carbon out of their carbon-intensive industries.

But carbon capture faces bigger, more immediate challenges than either controversy or canceled DOE grants: It’s expensive, generally unprofitable, and still not all that great at actually capturing and storing carbon. As the Trump administration continues its quest to kill measures that might have forced corporations to clean up their acts, moreover, some of the main drivers of corporate interest in the technology are disappearing. Countries and companies alike have walked away from climate goals that, in some cases, would have relied heavily on carbon capture to be met. If policymakers aren’t going to make companies cut carbon emissions, why would companies keep pouring billions of dollars into costly, arguably ineffective technologies to do just that?

The simple answer is that there are still plenty of subsidies available for it. A substantial tax credit known as 45Q—offering a maximum of $85 per metric ton of captured CO2—was preserved in the budget proposal the House sent over to the Senate late last month. Yet it’s still not clear what version of the GOP’s megabill will eventually pass, and fiddling with certain conditions of that subsidy could make or break some companies’ ability to court financing.

The Department of Energy’s clawing back of its awards hasn’t riled the industry as much as lingering uncertainty about the fate of federal tax credits, said Anika Juhn, an energy analyst at the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis. “In general, most of the companies that are working on projects that integrate CCS are in this ‘wait and see’ moment around 45Q,” she told me.

Even with tax credits available, the longer-term economics of the technology remain uncertain. Rohan Dighe, an analyst at the energy consultancy Wood Mackenzie, told the Financial Times that 45Q “is and continues to be insufficient to justify widespread deployment of post-combustion carbon capture.”

Even those critical of the exorbitant expense and energy demand of carbon capture for coal and gas power see potential for using it in limited circumstances. Two-thirds of the greenhouse gas emissions involved in cement production, for instance, come from heating up limestone so as to calcify it; that chemical reaction produces carbon dioxide as a by-product. With alternatives still fledgling, capturing carbon from cement production might significantly reduce pollution from an industry responsible for as much as 8 percent of global greenhouse gas emissions. Scenarios compiled by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, on paths for limiting global warming to 1.5 and two degrees Celsius (2.7 and 3.6 degrees Fahrenheit), are also largely premised on the world figuring out how to rapidly scale up its ability to capture and store carbon. There are compelling arguments, that is, for investing in CCS and trying to make it work. But corporate polluters aren’t in the business of meeting climate goals, and their investments in CCS will be guided by where they can profit the most, not how they can reduce the most emissions.

There are quiet signs that the Biden-era enthusiasm for carbon capture could be starting to cool. Earlier this week, the energy data and analytics group Enverus Intelligence Research reported that applications to store captured carbon fell by 50 percent in the first quarter of 2025 from the same period the year before. Fewer applications were submitted then at any time since 2022, and none of those permits were approved. Industry experts say the dip has to do with uncertainty over federal tax credits, and fears that 45Q could get swept up in the GOP’s broader legislative attack on the Inflation Reduction Act and the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act. For now, that doesn’t seem to be the case.

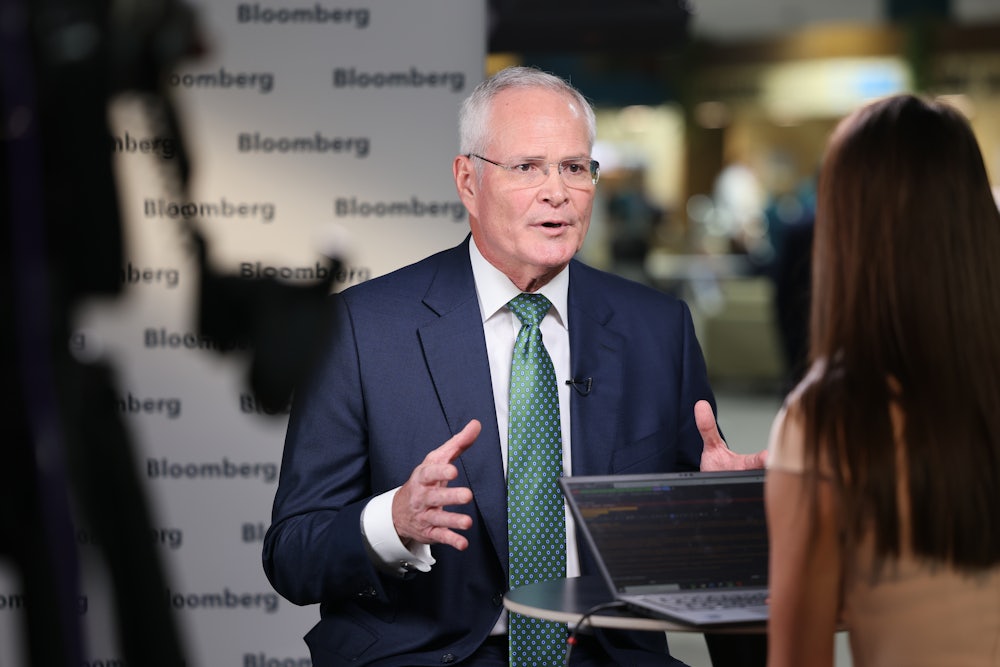

Republicans’ tax bill would, however, severely limit a provision making it much easier for smaller firms to take advantage of the tax credit. That could end up being a boon for huge companies that have already invested heavily in carbon capture. Among the grants being terminated by the Department of Energy is $332 million for a project at ExxonMobil’s Houston-area Baytown chemical plant, which aims to use CCS-derived hydrogen instead of methane gas in the production of ethylene, a feedstock for plastic resins and synthetic textiles.* Exxon hasn’t commented on the grant cancellation, but it’s a drop in the bucket compared to the company’s recent investments in carbon management. Exxon’s $5 billion acquisition of the pipeline firm Denbury in 2023 made it the largest owner and operator of CO2 storage in the U.S. Late last year, Exxon also secured a lease from Texas for the country’s largest offshore CO2 storage site.

Why does Exxon want to be in the carbon management business? There are modest but growing markets abroad for carbon-derived products like ammonia. Although Exxon’s Baytown hydrogen plant has yet to reach a final investment decision, the company has signed offtake agreements with Mitsubishi, the South Korean firm SK Inc., and Japan’s Marubeni Corp., which intends to use Exxon’s ammonia to fuel a gas-fired power plant there. ADNOC—the United Arab Emirates’ state-owned oil-producer—acquired a 35 percent equity stake in the project last September. Stateside, Exxon has also inked major deals with deep-pocketed tech companies to provide gas power to data centers for AI, premised in part on the idea that it’ll at some point be “net zero emissions” thanks to carbon capture. Even if the U.S. isn’t poised to demand that oil and gas companies reduce their greenhouse gas emissions, other countries might. Starting in 2026, the European Union, for instance, will tariff importers of carbon-intensive goods like hydrogen and ammonia. Equipping petrochemical manufacturing operations with carbon-scrubbing devices could ease compliance. Given Exxon’s size, moreover, an injection of federal dollars could set the company up to control whatever market for carbon storage does develop in the U.S., even if actual climate regulations are a long way off.

For now, the Trump administration is preserving Exxon and its competitors’ right to spew as many greenhouse gases as they want. Corporations continuing to invest in carbon capture may represent a longer-term bet that some kind of regulation on CO2 will happen eventually, either through more widespread carbon pricing or direct regulations of greenhouse gas emissions. Two things can be true: Companies like Exxon intend to continue drilling for oil and gas for as long as possible, and they also see a modest yet growing market for certain low-carbon technologies that they have the cash and expertise to gain a foothold in. This isn’t exactly great news for the planet. Mostly, it’s a reminder that a proliferation of “green technologies” doesn’t spell the end of dirtier ones.

*The article was updated to clarify which project at Exxon’s Baytown facility had received a grant from the Department of Energy.