Donald Trump’s assault on the city of Chicago began in September, and it claimed its first casualty quickly. As Reuters would later report, on September 12, Silverio Villegas-Gonzalez dropped his kids off at their school in the suburb of Franklin Park on his way to his job at a diner on the northwest side. Villegas-Gonzalez had come to the United States in 2007 to flee the violence in his home state of Michoacán, Mexico—violence wrought by the Mexican government’s militarization of its drug war, a policy encouraged and funded by the United States. (In November, the mayor of the city of Uruapan was assassinated after calling for a crackdown on organized crime.)

Described by friends and co-workers as kind and soft-spoken, Villegas-Gonzalez had two sons and met a woman from his hometown as he worked long hours in kitchens around the city.

After he dropped off his sons on the morning of September 12, two Immigration and Customs Enforcement officers approached the 38-year-old in his car. He put the vehicle in reverse and attempted to flee. One officer continued to chase him on foot and eventually fired his weapon, striking Villegas-Gonzalez, who crashed into a delivery truck and was pronounced dead an hour later. Officials of the Department of Homeland Security would later say that Villegas-Gonzalez “drove his car at law enforcement officers,” a claim clearly refuted by surveillance video. DHS also claimed the officer who killed Villegas-Gonzalez had been struck and dragged by the car and feared for his life. That allegation is more difficult to confirm or refute—the officer is obscured by the car in the video. The officer was later treated for “minor” injuries.

Villegas-Gonzalez had no criminal record. Over eight years, he had only a series of traffic citations for offenses like a broken taillight and driving without insurance. His most serious citation was for driving 30 miles per hour over the speed limit. In its press release laying out the ICE agents’ version of events, DHS referred to him as “a criminal illegal alien with a history of reckless driving.” The release included the striking line, “The illegal alien was pronounced dead.”

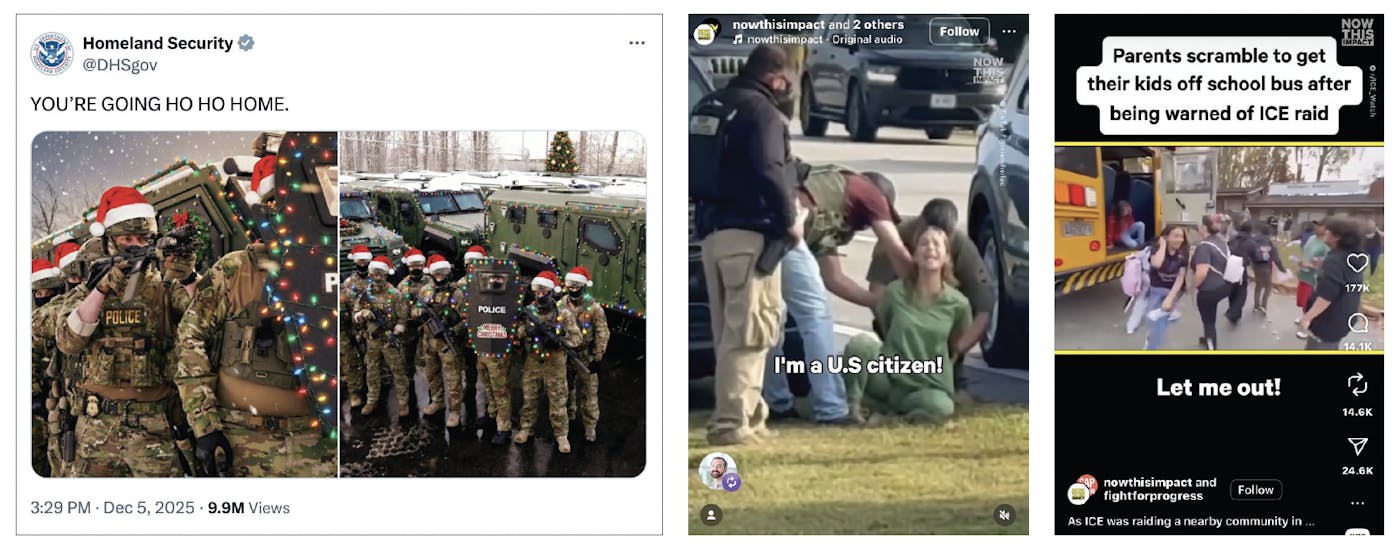

In the weeks that followed, immigration agents continued to arrest parents and nannies as they dropped off and picked up children from school, a tactic unheard of in prior administrations.

Videos posted to social media showed ICE and Border Patrol agents pointing their guns at unarmed protesters, unnecessarily tackling children and elderly people, and shutting down streets and intersections as they extracted people from their cars. Agents tear-gassed entire neighborhoods, in some cases enveloping schools and even Chicago Police Department officers in clouds of chemical irritant. Videos showed federal officers engaging in Precision Immobilization Technique, or PIT, maneuvers to cut off fleeing vehicles, a dangerous tactic banned or limited by the Chicago Police Department and many other police agencies in the country. On at least three occasions, ICE officers violently pulled U.S. citizens from their cars and detained them, claiming the drivers had deliberately crashed into agents—despite video and witness accounts contradicting the officers’ narrative.

As October dragged on, the raids intensified. Toward the end of the month, immigration officers gassed a neighborhood just hours before a scheduled Halloween parade for children. Illinois Governor JB Pritzker asked the administration to pause the raids on Halloween night so Chicago kids could go trick-or-treating without fear of being gassed, witnessing traumatic arrests, or seeing their parents or caretakers apprehended and detained. DHS Secretary Kristi Noem refused, calling the request “shameful.” Activists in Los Angeles would later photograph immigration officers, in an especially galling display of cruelty, wearing Halloween masks depicting horror movie villains while conducting immigration raids. When the citizen journalism site L.A. Taco asked DHS for comment, a spokesperson replied, “Happy Halloween.”

Trump has launched similar federal crackdowns in Los Angeles, Washington, Charlotte, Memphis, Minneapolis, and New Orleans, and threatened them in Baltimore, San Francisco, New York, and other cities. He has sent National Guard troops into Los Angeles and Memphis, and has promised to send more to other cities, along with active-duty troops. With astonishing speed, the administration has toppled the most cherished pillars of a free society. Masked secret police now tear-gas entire city streets, jump out from unmarked vehicles to abduct and detain suspected undocumented people, and demand that foreign-looking people (mostly Latino) produce papers on demand. These deportation forces have been told by the president and his advisers to cast a wide net, that immigrants are “animals,” that the activists defending them are “domestic terrorists,” and that the officers themselves have “immunity” from any form of accountability. Meanwhile, administration lawyers have brazenly lied to federal judges to supplement those deportation forces by deploying U.S. troops to the streets of American cities—seeking to break this country’s healthy antipathy toward domestic use of the military policing that dates back to the founding.

“They’re assaulting basic democratic ideals on all fronts,” said Dana Marks, an immigration judge who retired in 2021. “It’s really just classic authoritarianism. It always starts with the minorities. It always starts with the immigrants. If we don’t stop them, it will be American citizens. Congress, the courts, the people, we should all be jumping up and down and screaming about this. We need to be screaming that this isn’t America—that this isn’t who we are.”

“A Disgrace to Policing”

I’ve been writing and reporting on policing in the United States for more than 20 years. I’ve spent much of that time writing about the effects of police militarization, or the way military weapons, training, uniforms, and culture have infiltrated domestic law enforcement agencies. But I’ve never seen anything quite like the last six months.

We’ve seen rapid normalization of abuses we once associated with authoritarian regimes or the old Iron Curtain countries. It’s now routine for masked, unidentifiable government agents to sweep people off the street and whisk them away in unmarked vehicles. Some of those arrested have been quickly shuttled off to detention facilities in other parts of the country without any notification to their families or attorneys. Others have been sent to a third country, often a country in the developing world to which they have no connection. Still others have been explicitly targeted for their political opinions, their activism, or their journalism.

The phrase “your papers, please” has historically been the sort of demand we associated with Hitler’s SS or the East German Stasi. Immigration officers now routinely stop people who simply “look like” immigrants and demand they prove their citizenship or legal residency. Legal residents who fail to produce documentation on demand have been fined, and flustered immigrants who fail to produce sufficient records or recall a Social Security number have been arrested.

The administration is also shredding due process. The United States government has extradited immigrants to a torture prison in a foreign country after lying to a judge, then falsely claimed it was helpless to get them back. Immigrants are now stacked in detention centers under already inhumane conditions that appear to be deteriorating. And in a brazen contravention of a principle ingrained in the American founding, the president and his aides have claimed the power to deploy active-duty troops in cities they allege have been overrun with migrants, crime, or homeless people—or merely those overseen by mayors or governors the administration dislikes.

Most alarmingly, the administration no longer feels obligated to even pretend that it’s observing norms and constitutional restrictions. “They just don’t care when judges or the public says they’re violating the law,” one longtime immigration judge, now retired, told me. “That’s unheard of in my lifetime.”

Over the last year, I’ve spoken to and met with immigration attorneys and advocates all over the country. Many who openly spoke with me prior to the 2024 election are no longer willing to be quoted, fearing retaliation against their organizations or their funders, or even against them personally.

In more recent months, I’ve also interviewed former ICE and Customs and Border Protection officials, and former Immigration Court judges who served across multiple administrations of both parties. Career legal and law enforcement officials tend to be circumspect in their critiques of fellow law enforcement officers. They tend to avoid casual references to police states, or comparing U.S. police agencies to those in authoritarian countries. That’s no longer the case. These career police executives and prosecutors now use language I’ve rarely heard from current or former government officials in my career.

“What we’re seeing is a disgrace to policing,” said Reneé Hall, president of the National Organization of Black Law Enforcement Executives, or NOBLE. Hall compares the tactics used by ICE and Border Protection officers to the worst abuses of the civil rights era. “We’ve made a lot of progress in policing,” she said. “They’ve wiped it out in months.… We’re back to letting police target people because of their skin color. We’re letting them kidnap people and take them to undisclosed locations. They’re barging into homes with no warrant. We saw them zip-tie young Black children—U.S. citizens—in Chicago. We’ve seen them use unnecessary force, slam people on the concrete. If I were just watching these incidents on television, I would think that we were not in the United States of America. Back then they wore hoods. Today they wear masks.”

“I’m horrified by what I’ve seen,” said Chris Magnus, who served both as Joe Biden’s CBP commissioner and as police chief of Tucson, Fargo, and Richmond, California. “I wish the public had a better understanding of the harm they’re doing. Because it’s going to take a very long time to undo.”

“I wish I had something better to say than that it’s really bad,” another former senior Department of Justice official told me. “But it’s really fucking bad.”

The new federal budget Trump recently signed into law will triple the ICE budget and significantly increase the budgets both for Border Protection and for the construction of new detention centers. Trump’s deportation force will be larger than all but a handful of foreign militaries. According to the Brennan Center, the 2025 budget for immigration enforcement already exceeds that of every other federal law enforcement agency combined. And going forward, spending from the “Big Beautiful Bill” on immigration alone will exceed total spending by every state and local police agency in the country.

And if there’s one thing this administration has made clear, it’s this: What happened in Chicago will soon be happening in cities around the country.

Government Lawyers Are Lying in Court

One of the more maddening patterns playing out in the federal courts right now is the administration’s exploitation of a legal principle called “the presumption of regularity.” The legal doctrine instructs courts to presume that government lawyers argue in good faith and don’t deliberately misrepresent facts. The doctrine has rarely been a problem, because most administrations have argued in good faith, even when making bad arguments.

This administration is different. As of this writing, in the months since Trump’s second inauguration, the site Just Security has documented more than 60 instances in which federal courts have ruled that Justice Department attorneys misrepresented the facts or the law. Some judges have done so with unusually frank language, including accusing the administration of outright lying. One judge wrote, “Trust that had been earned over generations has been lost in weeks.”

Many of Trump’s power grabs are grounded in “emergency powers” exceptions that Congress or the courts have built into constitutional or statutory restraints on executive power. These powers have always been a glitch in the system. Dozens of emergencies declared with good intentions at the time have lingered over the years, as new administrations simply renew them without much oversight from Congress. Many concern sanctions against international figures involved in crime, drug smuggling, or weapons trafficking.

But the current administration has exploited those exceptions like none before. Trump has declared nine new emergencies since January. His tariffs, for example, are based on a law allowing the president to temporarily impose tariffs in response to an emergency. But he has threatened and imposed tariffs for clearly illegal reasons, such as slapping sanctions on Brazil for prosecuting former President Jair Bolsonaro for an attempted coup, or on Canada for accurately using footage of former President Ronald Reagan in a TV commercial.

The presumption of regularity and the enormous deference the Supreme Court demands courts show to the executive branch mean that any challenge to one of these declarations faces an uphill battle to prove that the administration is misrepresenting the facts or acting in bad faith in each individual case, even though it has shown an almost routine willingness to lie in other cases. And nowhere is this disconnect more striking than in Trump’s obsession with putting troops in American cities.

Using the Military as a Police Force

The norm against using troops for routine law enforcement is one of America’s most important contributions to democratic governance. It’s a principle we came by honestly, from firsthand experience. Prior to the American Revolution, the British crown stationed soldiers in the streets of Boston to enforce tariffs and import taxes. The soldiers were armed with general warrants that gave them carte blanche to force their way into homes in search of contraband. The abuse of those powers sowed anger and ignited revolutionary fervor.

Lessons from Boston lingered after the Revolution and instilled in the Founders a deep distrust of standing armies. “A large standing Army in time of Peace hath ever been considered dangerous to the liberties of a Country,” George Washington wrote in 1783. Four years later, at the Constitutional Convention, James Madison cautioned, “A standing military force, with an overgrown Executive will not long be safe companions to liberty.”

After fierce debate, the Framers of the Constitution reluctantly concluded that the threats posed to the new republic still demanded an army at the ready. But to guard against abuses, they divided control of the military between the executive and legislative branches. Still, the fears about domestically deployed troops spilled into the Bill of Rights debates the following year. It’s why we have a Second Amendment (the purpose of the state militia “is to prevent the establishment of a standing army, the bane of liberty,” Elbridge Gerry declared), as well as the Third Amendment protection against the forced quartering of soldiers, and the Fourth Amendment protections against unreasonable searches and seizures.

This fear of domestically deployed troops has become ingrained in America’s DNA. Presidents have deployed active-duty troops within U.S. borders only sporadically, and almost always temporarily. The most common reason for doing so early in the republic was to put down labor uprisings, rebellions, and riots, and while there are legitimate reasons to question the motivations and propriety of those deployments, they were at least temporary and narrowly defined. The one exception was Reconstruction, which saw federal troops in Southern states for a decade. But that came after a bloody and destructive Civil War.

In fact, one of the healthier and most encouraging characteristics of American democracy is that this norm has only become more robust over time. One big reason—also a sign of a healthy democracy—is that the principle has become ingrained in the military itself.

In the late 1980s, for example, the Reagan administration wanted to deploy active-duty troops to fight the drug war on American streets. The plan was thwarted by opposition from the Pentagon. “One of [America’s] great strengths is that ... we do not allow the Army, Navy, and the Marines and Air Force to be a police force,” Marine Lt. Gen. Stephen Olmstead told Congress in 1989. “History is replete with countries that allowed that to happen. Disaster is the result.”

Prior to Trump’s deployment of 700 Marines in Los Angeles in June, no president had deployed active-duty troops to a U.S. city since the Los Angeles riots in 1992. And no president had deployed the military over the objections of a state governor since Dwight Eisenhower sent the 101st Airborne to desegregate Little Rock’s public schools in 1957.

The deployment of National Guard troops is much more common. But that’s nearly always done by governors calling up their own Guard troops, sometimes to put down riots or protests, but more typically to aid with disaster response after hurricanes and tornadoes. Trump’s deployment of National Guard troops in Los Angeles is the first time a president has deployed the Guard over the objections of a state governor since 1965.

Trump is a well-documented admirer of dictators and strongmen and has made clear that he harbors little reverence for this firewall between the military and domestic policing. In his first term, Trump wanted to deploy troops to put down the George Floyd protests, if possible by “shooting them in the legs.” He was thwarted by more levelheaded senior staff, including Defense Secretary Mark Esper and Joint Chiefs Chairman Gen. Mark Milley. Trump and his second term advisers have made clear that they won’t tolerate that sort of dissent this time around. To fully implement his vision for the country, they’d need to purge the federal government of institutionalists and those who put democratic values and the rule of law over subservience to the president. As JD Vance put it in a 2021 podcast interview, “Fire every single midlevel bureaucrat, every civil servant in the administrative state, replace them with our people.”

Trump found his enforcer in Pete Hegseth, a man who is not only the least-qualified person ever nominated for secretary of defense, but whose record—which includes allegations of alcohol abuse and sexual assault and running two veterans’ nonprofits into the ground—should have been disqualifying. Trump really only had two prerequisites for the position. He wanted someone who loathed Pentagon institutionalists like Milley and Esper, and someone he could count on to be loyal. Here, Hegseth was more than qualified—embarrassingly so.

Hegseth has also echoed Trump’s contempt for the Pentagon’s healthier, democratically grounded principles. In his book, he has argued for enlisting the military in a modern-day crusade. And prior to 2025, other than his weekend co-hosting duties on Fox News, Hegseth was probably best known for lobbying Trump to pardon troops convicted of conscience-shocking war crimes.

After his confirmation, Hegseth dutifully began purging the Pentagon of its Milleys and Espers. He dismissed dozens of senior officials with centuries of experience (particularly those who weren’t male and weren’t white). Importantly, he also purged senior-level Judge Advocate General’s Corps, or JAG, officers, the attorneys who provide legal guidance on critical issues like rules of engagement or, say, the legality of deploying troops in U.S. cities.

The administration has since been caught brazenly lying to federal courts to justify Trump’s military interventions. In Portland, Oregon, a Trump-appointed Federal District Court judge wrote that Trump and the DOJ’s claims that the city was “war ravaged” and “under siege” were “simply untethered to the facts.” The administration was later found to have vastly overstated to the court the number of federal officers it had sent to Portland to protect federal facilities.

Meanwhile, in Chicago, a federal judge rejected the administration’s claims that the city was under “coordinated assault” by unnamed “violent groups … actively aligned with designated domestic terror organizations.” The judge chided the administration for its “lack of candor,” which, she wrote, “calls into question their ability to accurately assess the facts,” and noted a “troubling trend” of DOJ officials “equating protests with riots.”

Creating a Secret Police Force

The most alarming images to emerge from the first year of Trump’s second term are those of immigration officers in balaclavas, gaiters, and ski masks stopping immigrants on sidewalks and demanding proof of citizenship, chasing day laborers and landscapers through parking lots and city streets, or emerging from unmarked vehicles, snatching people off the streets, then quickly carrying them away.

Those unmarked vehicles are often rented, and officers have been caught swapping out license plates to prevent themselves from being identified—or just not bothering with license plates at all. “The agency clearly wants to appear like a ghost,” one former Baltimore ICE official told NPR. “I have never experienced this.”

“When law enforcement officers of any kind wear masks and withhold their identity, it smacks of tactics that are consistent with an authoritarian government,” said Magnus, the ex-police chief and former head of Border Patrol.

“We’ve had police here for two centuries,” said George Pappas, an immigration judge whom Trump’s Justice Department fired in July. “They didn’t need masks. You use masks when you’re looking to carry out an illegal, extrajudicial operation. This is straight from the fascist playbook.”

The images and videos of masked agents have provoked alarm in law enforcement and legal communities. They’ve been criticized by groups ranging from the New York City Bar Association to the International Association of Chiefs of Police. Even the FBI has asked DHS to remove the masks, pointing out that criminals have committed robberies and sexual assaults while impersonating immigration officers.

But more to the point, masked secret police jumping out of vans to snatch people up and whisk them away isn’t supposed to happen in a free society. It’s the sort of thing we’ve cited to distinguish ourselves from military juntas or, more recently, from countries like Brazil or the Philippines, where masked officers have carried out horrific extrajudicial killings by the thousands. Or from Russia, where the spectacle of masked police carrying out illegal and undemocratic orders is common enough to have birthed the term “mask show.”

Those distinctions are getting harder and harder to make. Trump has lavished praise on the current and former authoritarian leaders of all three countries, often specifically for their despotism. He praised Philippines President Rodrigo Duterte explicitly for his drug war policies, which even then were known to include sending masked police teams to execute thousands of drug offenders. Because of those killings, Duterte is now facing trial at the International Criminal Court for crimes against humanity.

Anya Bidwell heads up the Project on Immunity and Accountability for the Institute for Justice, a libertarian law firm. IJ is currently representing two U.S. citizens who were wrongly arrested and detained by immigration officers. “I was born in what was part of the Soviet Union at the time,” she said. “So seeing these kinds of things chills me to the bone. It brings bad memories.”

DHS officials have dismissed such comparisons as hysterical and hyperbolic. They say masking is necessary to prevent activists from “doxing” immigration officers and claim there has been an alarming surge in assaults on those officers. In June, they put the increase in assaults at 413 percent; by July, it was over 700 percent; and by October, it was over 1,000 percent.

Those figures are deceptive. The 2024 baseline figure against which the administration is making these calculations is 10, according to Fox News. That is, there were 10 alleged assaults on ICE officers between January and June 2024. There were 79 in 2025. Meanwhile, over the same period, the number of federal agents participating in deportations and removals has swelled from 6,000 to over 30,000. That puts the assault rate on federal immigration officials (0.23 per 100) exponentially lower than the assault rate on police officers more generally (13.5).

Given the ramped-up immigration enforcement and the exceptionally violent and aggressive tactics, we’d expect to see an increase in assaults on agents. More interactions, and more violent interactions, mean more opportunities for those interactions to escalate. We also know from surveillance and cell phone videos that agents have arrested and charged people with assault either on little evidence or for defending themselves when assaulted by police. After an ICE officer shot a Chicago woman named Marimar Martinez five times, for example, the administration claimed she had intentionally boxed agents in with her car and fired a gun at them. She was arrested and charged with assault. After that account was contradicted by witnesses and video, Martinez was released without charges.

“The mask issue really burns my biscuits,” said Reneé Hall. “I patrolled in the city of Detroit for nearly 20 years. I lived in the place that I policed. I didn’t get to hide my face. And you know what? Every other police officer across this country arresting people for drugs, for violent criminal acts, for gang violence, show their faces, too. My father was a police officer who was killed on duty. He never would have dreamed of hiding his face from the people he served. These federal officers are coming into these communities from other places, hiding their faces, using unnecessary force and violence, and then just walking away. That isn’t how it works. Hell no to that.”

There are, of course, limited circumstances in which it may be justified for police officers to shield their identities—officers who investigate organized crime, for example, or who frequently work undercover. So there are no federal laws that prohibit it. But the most important reason U.S. police don’t wear masks isn’t grounded in the law, but in democratic values. “I find the masking absolutely fucking horrific,” said “Bryan,” a former high-ranking official in the DOJ. “It’s not something we do in a free society. It’s what they do under regimes we should never be emulating. It’s about intimidating and terrorizing.”

That shared understanding has broken down under an administration that seems to emulate those regimes, and that has made clear that it wants to instill fear and terror in immigrant communities. They aren’t letting federal immigration agents terrorize neighborhoods like Chicago’s Little Village because terrifying these places makes them safer. They’re doing it because they don’t believe neighborhoods like Little Village should exist. “The president’s goal is to create fear and anxiety,” said Michael Rodriguez, an alderman whose district includes the heavily Mexican American neighborhood. “It’s a sinister agenda to relitigate the Civil War. I don’t think that’s vitriol. This country is becoming majority minority, and they can’t handle that. So they’re turning to xenophobia to reverse the trend.”

One needn’t look far to validate Rodriguez’s fears. Stephen Miller, who has been traipsing about the fever swamps of white nationalism for years, has made it no secret that he wants to reduce immigration from nonwhite countries to zero. Trump has echoed the sentiment, bemoaning at one point why so many immigrants come from “shithole countries” (the countries he’s named have all been predominantly Black and brown), and so few from countries like Norway or Switzerland. It’s now been widely reported that by the end of Trump’s second term, the bulk of the country’s refugee program will be redirected to aid white farmers from South Africa.

Placing Law Enforcement Above the Law

The most basic definition of a police state is a society in which the police themselves are above the law. In 2024, Donald Trump campaigned on promises to make police officers completely immune from both criminal prosecution and civil liability. Whether a president could actually do that isn’t as important as the fact that a major party’s nominee for president was, quite literally, promising to turn the country into a police state. And then he won.

The United States has long had a problem with holding bad cops accountable, and, to be fair, much of that problem predates Donald Trump. The George Floyd protests in 2020 provoked public discussion about qualified immunity, a legal doctrine wholly invented by the Supreme Court in 1967 that makes it extremely difficult to sue state and local police for abuses that violate the Constitution.

Less discussed is that it’s even more difficult—all but impossible, really—to sue federal law enforcement officers. For years, the only real avenue to do so was through the precedent set in the 1971 Supreme Court case Bivens v. Six Unknown Named Agents. But the court has been gradually chipping away at that case ever since and all but overturned it in 2022. There is one remaining, far more complicated law, the Federal Tort Claims Act, which lets people sue federal police officers, but to sue under that law is an immensely complicated process. The law also bars punitive damages, and it, too, is being eroded by the federal courts.

“People ask me questions like ‘Is it constitutional for them to wear masks?’ or ‘Can they really detain U.S. citizens incommunicado?’ or ‘Is it really legal for them to scare children like that?’” said Bidwell, the IJ attorney. “The answer is that it doesn’t matter if what they do is legal. Because they know that fundamentally they can’t be sued, either as the government itself or individually.”

So while the administration sets arrest and deportation quotas, attacks immigrants with dehumanizing rhetoric, and tells immigration officers that they’ve been “unleashed,” Bidwell said, there’s nothing pushing back to keep deportation forces in line. “There’s no incentive for these officers to act in a cautious manner that’s compliant with the Constitution.”

“Back when I worked for ICE, there would occasionally be times when they’d inadvertently arrest or detain an American citizen or legal resident,” said Javad Khazaeli, who was an immigration prosecutor during the Obama administration and now works as an immigration defense attorney. (Disclosure: Khazaeli is also a friend.) “When that happened, it would be all hands on deck. It was like, OK, what went wrong here and how do we fix it? Now there’s nothing like that. Now they just don’t care.”

The immunity problem pervades the chain of command from top to bottom. Thanks to a spate of Supreme Court rulings from the case that all but killed Bivens, to rulings protecting political appointees for policy decisions, to the Supreme Court’s infamous ruling on presidential immunity, everyone is protected, from the Border Patrol officer who abandons a baby in the back seat of a car after detaining his immigrant parents (as happened in a suburb of Chicago) to the Border Patrol commander who tear-gasses elementary schools, to the president who says immigrants are “poisoning the blood of the country.”

That leaves only criminal liability. It seems unlikely that Trump’s DOJ would ever prosecute an immigration officer, even for egregious abuses. Some have suggested that local police and prosecutors arrest and charge Border Patrol agents caught committing clear crimes, or that states pass laws prohibiting masking by law enforcement, and then arrest officers who violate it. But state and local charges against federal police are almost always removed to federal court, where the officers would have an advantage, and would need only to show that their actions were part of their federal duties (though the case would still be overseen by local prosecutors). Trump’s DOJ is also likely to oppose such charges, and could potentially even assist in the officers’ defense.* There may be some value in bringing charges anyway to force the issue and draw public attention to these abuses. But they aren’t likely to bring much accountability. It’s yet another policy that, while in place over multiple administrations, could be particularly destructive in the hands of an administration so averse to the rule of law.

In the end, this administration has exposed how the Supreme Court has made the Bill of Rights almost entirely reliant on the executive branch’s willingness to police itself. If federal police officers can violate constitutional rights with impunity, those rights may as well not exist.

Trump’s immigration agents are erasing accountability in other ways, too. They’re specifically targeting journalists who report on their actions. In Chicago, they tackled and arrested a WGN producer, claiming she threw something at ICE officers—an allegation that was disputed by witnesses. She was later released without charges. In June, the administration arrested an immigrant journalist in Georgia who had been reporting on immigration raids. At his deportation hearing, DOJ lawyers explicitly argued that his journalism was a threat to public safety. He has since been deported. In Los Angeles, immigration officers shot a citizen journalist who had built an online following for streaming ICE raids. They claim he rammed his vehicle into theirs. He was arrested for assaulting a federal officer. In Texas, another freelance journalist and DACA recipient had his status revoked and was arrested for “glorifying terrorism” over social media posts after he advocated at a city council meeting for a Muslim man who had recently been detained.

Shortly after the raids on Home Depot parking lots and car washes began in L.A., civil and immigration rights groups filed a lawsuit accusing the administration of racially profiling Latino people. Notably, a federal judge ordered the government to stop, and arrests dropped dramatically. The Supreme Court eventually ordered a pause on that temporary restraining order, allowing raids and stops based on skin color, language, and presence in areas where immigrants live and work to continue.

There was no majority opinion, but in a concurring opinion, Justice Brett Kavanaugh wrote that people who are in the country illegally have no right not to be racially profiled. As for U.S. citizens or legal residents, Kavanaugh wrote, once immigration officials establish legal status, “they promptly let the individual go.”

In a dissent, Justice Sonia Sotomayor wrote that Kavanaugh’s “concurrence improperly shifts the burden onto an entire class of citizens to carry enough documentation to prove that they deserve to walk freely.” It effectively made anyone who “looks immigrant” into a second-class citizen.

Kavanaugh added that if immigration officers violate other rights of citizens or legal residents, such as by using excessive force or not “promptly letting that individual go,” those people could always sue. It had been just three years since Kavanaugh joined the majority in all but overturning Bivens, effectively shutting down the right to sue federal law enforcement.

Kavanaugh’s claim that citizens and legal residents would simply be “let go” hasn’t held up. About a month after the ruling on racial profiling, ProPublica published a report documenting 170 cases in which immigration officers had detained U.S. citizens. The publication found 130 cases in which U.S. citizens had been arrested for allegedly interfering with immigration operations or assaulting officers but were often never charged. It found over 20 cases in which U.S. citizens were held for more than a day without being permitted to contact an attorney or their families. “Americans have been dragged, tackled, beaten, tased and shot by immigration agents,” the publication wrote. “They’ve had their necks kneeled on. They’ve been held outside in the rain while in their underwear. At least three citizens were pregnant when agents detained them. One of those women had already had the door of her home blown off while DHS Secretary Kristi Noem watched.” More recently, immigration officers stopped a Latino U.S. citizen in Los Angeles during a raid on a Home Depot. They arrested the man for an alleged assault and weapons violation, then drove off in his vehicle with the man’s one-year-old daughter still in the back seat. All of this in just the first 10 months of the new administration.

“This version of the Trump administration is a stress test for the United States,” said Bidwell. “They’re very good at identifying cracks in the system, then working at those cracks to widen them. These gaps in accountability for federal police have been around for a long time. We’re going to see how bad it can get when those gaps are exploited by an administration with no respect for constitutional restraints.”

Shredding Due Process

In a different world, immigration judges might be a check on all this abuse by immigration officers. But that isn’t the world we’re inhabiting. Despite their name, immigration courts have always operated within the executive branch, not the judicial, so they lack the independence of federal courts. Still, previous administrations mostly just tinkered with these courts at the margins, replacing judges as necessary with judges more in line with their policies. The Trump administration has changed all of that. Shortly after the inauguration, the DOJ issued memos to immigration judges making clear that they’d be expected to support the administration’s deportation goals. “There was a drastic change in tone,” Pappas said. “They were denigrating the people before us in terms of leadership, calling judges and leadership in the courts unethical and unprofessional.”

The following month, the firings began. Since February, DOJ has fired at least 98 immigration judges, and another 55 or so left voluntarily after seeing the writing on the wall. “Amanda” was one of the first judges fired in February. “I was never told why I was let go,” she said. “A lot of people were shocked. I don’t think anyone would have described me as a liberal judge. I’m a former immigration prosecutor. The feeling was that if they’d fire someone like me, no one was safe. Which is probably the message DOJ wanted to send.”

Amanda said there was one incident in her record, when she worked for the Executive Office of Immigration Review, that may have flagged Trump’s DOJ. “I was once reported for engaging in ‘illegal DEI,’” she said. “One of the individuals I supervised moved the seating arrangements for African American staff to the same undesirable hallway, causing staff to refer to that hall as ‘Jim Crow Row.’ I told her she had to stop doing that. When this new administration called for reporting of ‘illegal DEI,’ the staff member forwarded an email to me to notify me that she had reported me. Maybe that’s why I was fired. But my termination notice was a few sentences long. So who knows.”

In October, the DOJ announced that it would begin appointing military lawyers from the JAG Corps to serve as temporary immigration judges—the officers who had survived Hegseth’s purge. The move has been widely derided in the legal community as an effort to turn the courts into little more than a rubber stamp for the administration. “Immigration law is incredibly complicated,” Pappas said. “There’s just no way you’re going to be able to pick it up in a matter of weeks and treat these cases with the judgment and care they require.”

The most immediate effect of the administration’s politicization of immigration courts will be in denials of asylum claims and in expedited removal orders and deportations. “Immigration courts are like litigating death penalty cases in a traffic court setting,” said Marks, the longtime immigration judge who retired in 2021. “When you deny asylum to someone, there’s a real possibility that person will turn up dead after they’re deported.”

Trump has also purged the board that hears immigration appeals and replaced those members with his own appointees. The new, Trump-friendly version of the board then announced that judges could no longer order bond for anyone in the country illegally. That decision—which has been roundly rejected when challenged in federal courts—potentially means millions more people in federal detention, where conditions are rapidly deteriorating.

This, too, is all part of the plan. Miller, Tom Homan, and the architects of the child separation policy during Trump’s first term have made clear that one goal of their immigration policy is to disincentivize people from coming to the United States by inflicting suffering on those who do. One way to make people suffer is to take away their children. Another is to stuff them into overcrowded cells, deny them access to a shower, medication, and clean food and water, and make it all but impossible for them to contact their families or attorneys. Human rights groups have already documented these and other inhumane conditions at detention facilities all over the country, including at brand new centers like “Alligator Alcatraz” in Florida.

It Is Happening Here

When Trump took office in January 2025, there were 39,000 people in ICE custody. By September, there were more than 60,000, and there will be capacity for around 107,000 by January 2026. As of this writing, 23 people have died this year in ICE custody. That’s the most since 2005, and more than the previous three years combined. The conditions faced by those in custody are only likely to get worse as deportation efforts continue to ramp up.

At the same time, the administration has hollowed out the offices within DHS and DOJ that oversee detention facilities. “There’s no oversight. There’s no reporting. There’s no access,” said “Dan,” a longtime former DHS employee and immigration prosecutor. “Until this administration, if a lawyer or an NGO complained about inhumane conditions, that was something we took very seriously. Now they just don’t care. It’s fully part of the plan. They’re open about it. You put people in detention, deny them access to a lawyer, and just continue to squeeze them until they’re so miserable that they give up their rights.”

In the midst of all of this, the Pentagon began engaging in this administration’s most egregious and brazen breach of due process to date: bombing boats in the Caribbean and eastern Pacific Ocean, off the coasts of Colombia and Venezuela. The Pentagon claimed the occupants of the boats were “narco-terrorists,” but provided no evidence to support the accusation—nor would it be justified to kill them if they were. Smuggling drugs is not a capital crime in the United States. It also seems unlikely that most of the boats were bound for the United States, and neither Colombia nor Venezuela produces or exports significant quantities of fentanyl, the drug most responsible for overdose deaths in America.

The strikes are illegal, under both domestic and international law. The United States is not engaged in an armed conflict with drug cartels, drug cartels are not terrorists or enemy combatants, and the administration has provided no evidence beyond its say-so that the people it has killed fit into any of those categories. The administration later conceded that it doesn’t actually know the identities of the people it is killing, but that it would be legally justified to kill anyone who is “as much as three hops away from a known member” of a designated terrorist organization. Setting aside the fact that, again, drug cartels are not terrorist groups, sociological studies estimate that the average person knows about 600 people. This means that under the “three-hop rule,” which allows authorities to pursue individuals three “hops” away from the target, each member of a terrorist group would make about 216 million people eligible for legal assassination by the U.S. government.

As of publication, the administration had killed more than 83 people in 21 strikes. The strikes embody Trump’s most authoritarian instincts—unchecked and unreviewable executive power; crass imperialism; a feverish, 1980s-era approach to illicit drugs (Trump has frequently said that drug dealers should be executed); and xenophobic bigotry, particularly toward the developing world. Both Trump and Vice President Vance have even joked about the possibility that the strikes may have killed innocent people, delivering wry bons mots about how Caribbean fishermen probably don’t go out on the water much anymore.

The strikes are abominable, reckless acts of violence in and of themselves. But it isn’t difficult to envision how an administration with so little regard for law, human life, and due process might make the leap to think it can also carry out extrajudicial executions inside the United States, particularly one run by a president who equates criticism of him with treason, likens immigrants to vermin, and calls his opponents “the enemy within.” This, after all, is an administration already trying to legally define peaceful protesters and their supporters as “terrorists,” the same term it uses to justify those extrajudicial killings.

There would certainly be far more popular and political backlash to such strikes within U.S. borders, or against U.S. citizens. But public opinion isn’t a dependable bulwark against an administration that has anointed itself judge, jury, and executioner. It’s of little comfort in the throes of an administration that believes it can kill on demand, regardless of domestic or international law, and feels no obligation to justify its decision to do so to Congress, the courts, or the public.

Perhaps that sounds overwrought. But if you had suggested in 2024 that if elected, the Republican candidate for president would instruct federal police to sweep immigrants off the street—some of whom were here legally, and most of whom had no prior criminal record—put them on airplanes, and send them to a Central American gulag, all without ever letting them speak to a judge, you’d also have been called overwrought. But it is happening.

If you had suggested 10 years ago that federal agencies would use Nazi, fascist, and white nationalist iconography and allude to explicitly white supremacist literature in their social media posts, or that the Department of Homeland Security would use nativist, blood-and-soil messaging about preserving Western heritage in its outreach to recruit new immigration officers, you’d also have been called overwrought. But this, too, is happening.

If you had suggested during the Obama era that a U.S. president would encourage a violent assault on the U.S. Capitol in order to prevent his successor from taking office, that said president would then be reelected, would pardon all of the insurrectionists, and then go about erasing that history from official records, you’d also have been called overwrought. But Trump has done all these things.

During the week I finished this story, a federal judge ruled that the conditions at the main immigration detention facility in Chicago were “inhumane.” U.S. District Court Judge Robert Gettleman found that prisoners were being forced to sleep on top of one another, slept next to overflowing toilets, were provided with no beds or access to showers, didn’t have adequate food or medicine, and were forced to drink water that “tasted like sewer.”

The following day, in a separate lawsuit, U.S. District Court Judge Sara Ellis ruled that federal immigration officers in the city were using levels of force that “shocks the conscience.” She found that Border Patrol commander Gregory Bovino and other government agents had lied to her in court proceedings. In an impassioned opinion, Ellis mounted an eloquent defense of both the city of Chicago and American values, quoting Carl Sandburg and John Adams. She also ruled that federal forces were deliberately undermining free speech by detaining and beating protesters. “The freedom of speech is a principal pillar in a free Government,” she wrote, quoting Benjamin Franklin, “when this support is taken away the Constitution is dissolved, and Tyranny is erected on its Ruins.”

The next day, Bovino and his agents were back in Little Village, clashing with protesters. In the days that followed, they dragged a day care teacher out of her school as she screamed, used tear gas on large groups of protesters, and pepper-sprayed a one-year-old (they denied at least the pepper-spraying of the infant). Later, Bovino and his agents posed in front of Cloud Gate, the iconic sculpture more commonly called the Bean. According to local reports, the officers shouted out “Little Village!” as they mugged for a group selfie.

Just a few days before Ellis’s ruling, in a prime-time interview on CBS’s 60 Minutes, President Trump was asked if in tear-gassing entire neighborhoods, beating U.S. citizens, terrorizing children, and lying to federal courts—if given all of that—he thought that perhaps his deportation force in Chicago may have gone too far.

He answered, “I don’t think they’ve gone far enough.”

* This article previously misstated who oversees local or state charges that have been removed to federal court.