This is a lightly edited transcript of the February 17 edition of Right Now With Perry Bacon. You can watch the video here or by following this show on YouTube or Substack.

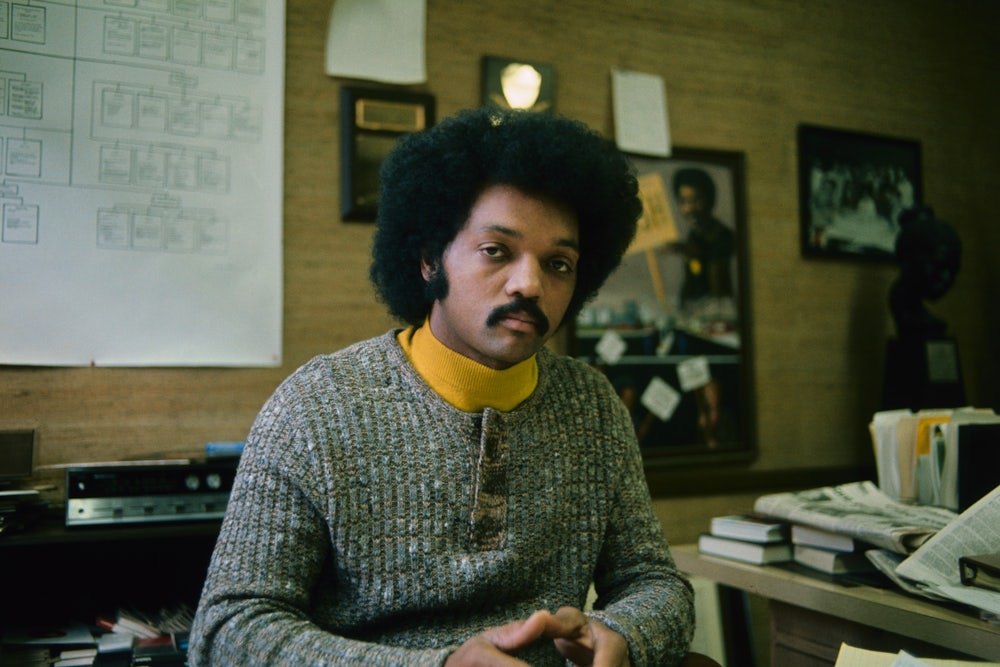

Perry Bacon: We’re going to talk about Jesse Jackson today. He passed away today, obviously, as you probably saw. We’re going to talk about his life, his legacy, and a little bit about politics of today and what things he did in the 1980s and 1990s might tell us about the future. So Danielle, thanks for joining me.

Danielle Wiggins: It’s great to be here. Thank you for the invitation.

Bacon: So I want to start with sort of the politics part, for lack of a better way to say that. You wrote this essay in Boston Review that came out earlier this month, and you argued that Democrats today, who are trying to think about where they should go and what they should do, should take some lessons from the ’84 and ’88 campaigns of Reverend Jackson. Talk about what you mean in that context.

Wiggins: Yeah, so I wrote that essay in response to a piece by Jacob Grumbach and Adam Bonica that basically argued that the Democrats should abandon what is an increasingly failing policy of moderation, which I happen to agree with. And I came at it through this historical lens by thinking about Jesse Jackson’s critiques of the Democrats’ initial turn to the center in the 1980s during the Reagan era.

And I show how Jesse Jackson understood very early on that the people who would be most harmed by moderation, by compromising with conservatism, by compromising with the Reagan administration; the people that would be most harmed by that would be poor minority people, people who were already victims of Reagan’s cuts to social programs and his general politics of moderation.

And so I suggest that he offered an alternative vision to the centrist sort of politics that was being proposed by moderate Democrats in the Democratic Leadership Council in the mid-1980s. And it was based really on a social democratic, populist agenda that sought to unite what he called the Rainbow Coalition.

He also used the allusion of a quilt. He liked using metaphors quite a bit as the country preacher, but it would unite these disparate groups—obviously racial minorities who he had been organizing for most of his career, but also dispossessed farmers, displaced workers, gay and lesbian populations who were being harmed by Reagan’s ignoring of the AIDS crisis.

He also included immigrants and the disabled and environmentalists and young people in this coalition that he called the Rainbow Coalition that was united by a shared grievance and a shared experience of harm by what he called “economic violence.”

And he described economic violence as these policies and practices of austerity that really were creating and deepening the wealth gap in the United States in the 1980s. And so he believed that this coalition could be mobilized.

And many of them—if we think about African Americans in particular—were demobilized in the Reagan era. They were very turned off by the Jimmy Carter administration and his failure to keep the promises that he had made about full employment and his walking away from a more robust urban economic development program.

So they were demobilized by the Carter era and were falling out of political participation, particularly at the national level. And so Jackson believed that these people who had been dejected and demobilized and didn’t see themselves as part of the political populace anymore could be mobilized and could create a coalition that would be powerful enough to defeat Reaganism.

Bacon: Let me stop you to say this in the most reductive way possible, ’cause I’m a journalist. In some ways, Jackson was an early critic of a lot of the sort of what we call, like, neoliberal economic policies.

And today, in some ways, the Democratic Party has sort of caught up to him. You see Bernie Sanders or Elizabeth Warren or AOC—even Biden at times. You’re seeing a Democratic Party that’s moved away, at least pre-2024. From 2018 to 2024, you saw a move toward what Jackson was talking about. He’s critiquing neoliberalism. Is that a good way to think about it?

Wiggins: Yeah, of course he wouldn’t call it neoliberalism; I think he would call it a milquetoast sort of moderation that was abandoning sort of the “New Politics” approach of the 1970s—meaning a sort of political coalition building that centered people that had previously been marginalized prior to the Voting Rights Act.

But yeah, absolutely. He was criticizing the rising power of corporations in the Democratic Party, the rising professionalization. And as I said before, he was very critical of the tendency to moderate and weaken core Democratic Party policies and principles to appeal to this mythic, mainstream centrist voter who was imagined by these Democratic Leadership Council members as white, middle-class, suburban Sun Belt [voters].

Bacon: And to read your essay, I assume we’re in the same place again. Your essay argues the Democrats can win by mobilizing the marginalized and having a real agenda for humans or people. And we’re again at this point where I don’t know who the DLC of today is. We have a lot of consultants and so on.

So they would come to you with this, like: The median voter is a white man who’s over 50 and who doesn’t have a college degree, who thinks Democrats are too woke and who may [like] Trump a lot.

So how do you respond to that? Because we’re still having the same argument today. Because in the ’80s, Reverend Jackson could not win, in part because he faced the sort of white, centrist argument: We’re too left, the special interests have taken over the party. So how do you respond to that today? ’Cause we’re having the same version of the same arguments today.

Wiggins: Yeah, well, I would definitely cite the work of Jacob Grumbach and …

Bacon: Adam Bonica.

Wiggins: Yes. Who have shown, using social scientific—they’re political scientists so they have the data to suggest that that tack is not working anymore.

They argue that it worked in the 1990s—that the tactic of triangulation worked, Bill Clinton being the most famous example, but they also show that it worked on local and state-level races as well. But they have shown that that isn’t working anymore. So there’s social science, there’s political scientific data to suggest that that is a losing game.

But I think as a historian, I would argue that that has never worked for people at the margins.

Bacon: It was always bad for Black people, even if it helped Bill Clinton win the election, maybe. Or we can debate that.

Wiggins: Exactly. So Bill Clinton, you know, the “first Black president,” I guess—very popular among African American voters. But, this is the expansion of the carceral state under Clinton, the evisceration of welfare, a distancing from the legacy of civil rights within a Democratic Party, or a kind of reformulation of it.

And so my argument would be that it’s never worked and that it has come at the expense of Black, poor, and other marginalized people.

I’ve also been, like many other people, very attuned to the Zohran Mamdani campaign and seeing a lot of echoes of the Jackson campaign in that campaign, particularly in how he was communicating with people and the way that he sort of mobilized a very clear moral vision that people could grab onto and become excited about.

And so I think that New York is an exceptional space, but I do think that that campaign does give credence to the sort of movement-based; a campaign that’s driven by a moral vision of what is right and what is wrong, and who is taking from whom, and is very clear about who our enemies are.

I do think that he has shown that there can be a model for that that can be obviously shaped to other spaces, particular conditions, but has shown that that Jacksonesque model can work in this post-2024 era.

Bacon: Let me move away from electoral policy a little bit, and I guess I’ve come to learn... you’re a historian, that’s why I want to ask you this. I used to think of the civil rights movement as, like: Brown v. Board is the start, and it ends maybe when King dies or something like that. And then Black Power takes over, and that turns off white people and so on. That’s the very simplistic story you learn even in college.

And I think there’s been more historical writing that I’ve read, and I think more people read, about the fact there’s been a “Long Civil Rights Movement” that sort of started at the beginning of the twentieth century, or really right after Reconstruction. You could probably say that lasts until now, or extends to Black Lives Matter.

But I want to talk about Jesse Jackson’s part of that. In my childhood, in the 1980s and the 1990s, Jesse Jackson is probably the most prominent Black figure for, like, two decades [for] a certain reason. Talk about his role. Talk about the civil rights movement of, say, 1975 to 2000, and what Jesse Jackson’s doing.

Wiggins: Yeah, and I think it’s important that you brought up the “long movement” paradigm and how historians rooted it in the 1920s and 1930s, where there’s a very clear economic critique that is paired with the racial critique or the critique of racial discrimination. And so the activists of the 1920s and 1930s were criticizing racial capitalism; the ways in which race and class intertwine to create a particular form of oppression that creates surplus.

Anyway, I say that because that is what Jesse Jackson brings back or really foregrounds in the 1970s. Of course, he is mentored by Martin Luther King. He kind of elbows his way onto the staff of the SCLC in 1965 in Selma, which has a complicated relationship with the other Southern Christian Leadership Conference members, but he’s mentored by King at this time that King is really starting to foreground the economic critique, as well. When he is starting to talk about defeating the three evils: racism, militarism, and capitalism.

So Jesse Jackson begins as someone who is fighting for Black economic rights and Black economic empowerment. His role in the SCLC was to run Operation Breadbasket in Chicago, which would organize these consumer boycotts against companies that refused to hire Black people or invest in Black communities. And he’s quite successful in winning thousands of jobs for people, for Black people, in Chicago. He leaves the SCLC for reasons that I won’t go into, creates his own Operation PUSH—or Operation People United to Save Humanity. And they’re still engaged in those boycott practices, as well.

And so his vision of the next stage of civil rights is what he would call, or he and others would call, the “dollar rights” or “green power,” which was pairing Black economic empowerment with a political power empowerment, as well. And so he is threatening to boycott major corporations like Anheuser-Busch, a lot of liquor companies, Miller, and he is demanding not only that they hire Black people at all levels but that they invest in Black communities, that they invest, they put their money in Black banks, that they hire Black subcontractors. And so this in ...

Bacon: The ’70s, ’80s, right?

Wiggins: The 1970s and ’80s, yeah. He continues this into the 1990s, as well—really into the 2010s there are these boycotts that come up, but he’s also calling for Black people in the boardroom. So at all levels he’s trying to promote this agenda of Black economic empowerment, and that’s how he understands the next wave of the civil rights movement. That we’ve gone from political rights to economic rights. Now he comes to understand the limitations of that, and that’s part of the reason why he begins to organize a political campaign, an independent political campaign.

Bacon: So in the ’80s, what is he doing when he’s not running for president?

Wiggins: He’s still continuing to work with Operation PUSH, and then Operation PUSH becomes the National Rainbow Coalition. So he’s still engaged in these kind of economic boycotts, trying to get Black people on board. He’s also the Jesse Jackson that I grew up with—a ’90s kid—he would come in when there was this moment of racial crisis.

Bacon: That’s what I remember most.

Wiggins: Yes. An instance of police brutality. I remember him coming in with the Jena Six case in 2005 to 2006. And so he also starts doing that where he, along with Al Sharpton, they swoop in and bring attention and money to these local organizing into local issues. So he is also doing that in addition to running for president. He is also engaged in foreign policy, as well. He is on the forefront of negotiating against apartheid in South Africa. He has his hand in a lot of different places.

Bacon: He ever actually run a church, by the way?

Wiggins: Not really. No. His church was, his church was Operation Breadbasket, and it was Operation PUSH and it was the Rainbow Coalition.

Bacon: So one thing in your book you talk about is—and there’s a Lily Geismer book that sort of hits—he loses these campaigns, and the neoliberalism of the party takes over, and he does some of the … he joins in some of the corporate partnerships, private ... he sort of moves to the right a little bit as the party does, right?

Wiggins: Yeah, it was always kind of there for Jesse Jackson. I mean, remember he’s saying that the next stage of the civil rights movement and Black empowerment is the dollars—economic empowerment. So he is already saying that the key to Black advancement is going to the corporations directly. Not going to the state anymore.

Bacon: Yeah.

Wiggins: Because it’s a hostile state, unless—he runs for president to change that. But he is, and this is part of what my book is about is a long Black tradition of what we could call privatism and working to improve the conditions of Black people’s lives and Black communities through the private sector. So not only through the private home and Black private organizations but also by partnering with corporations to start Black schools and to pay for civil rights organizing and to pay for legal defense. And so he’s really just continuing this tradition of corporate partnerships and what we would call public-private partnerships.

Bacon: We’re talking the 1980s, 1990s—the idea that the government’s going to spend more money is off the table. Clinton has literally said, the era of big government is over. So you sort of know that’s not on the table. And you knew the kind of spending we’d seen in the Biden years was not going to happen then, right?

Wiggins: Yeah. Black people knew before anyone else that the era of big government was over, and that was the Black condition. They were prepared for that. And so they had techniques, they had ways of raising money, they had ways of supporting Black organizations that are very old, that they bring back and intensify in the 1980s and 1990s. So when Jesse Jackson is seemingly engaged in these neoliberal practices of corporate partnerships and urban development programs and these pro-growth what we think of as like centrist initiatives, he is pulling from another tradition entirely that happens to dovetail quite neatly with what the neoliberal Democrats are doing. But it is coming from a different point of view, and it’s toward a different end as well.

Bacon: He’s a big defender of Clinton during the impeachment stuff, right?

Wiggins: Yes. I wonder how much of that is because of his own personal scandals that are happening around this time. But he tended to defend Clinton in public. Even if they had their disagreements, he did close ranks behind him, so we can understand him as supporting the Democratic candidate but at the same time also, knowing his personal history, that there might have been some personal reason why he was doing that.

Bacon: So how do you view this 1990s moment where the Democratic Party is trying to move? This is all part of the centrism story. You think it is both economic, it’s also like moving away from racial justice essentially.

Wiggins: Yes. I see the Sister Souljah moment as Clinton obviously making clear that he knows how to handle Jesse Jackson. That’s how it was reported, that he wouldn’t be beholden to Jesse Jackson’s demands. Because there is this narrative that the Democratic establishment was building that Jesse Jackson had this cult of personality that could sway Black people to do whatever.

Like you had the political adviser or something like that. ignoring all the critiques and, you know, yeah. The complicated relationship that many Black Americans had with him as a candidate, as a person. But he wanted to show that he could handle Jesse Jackson, that he would not be beholden to him. That he was willing to publicly embarrass him.

But I also think he wanted to demonstrate—or he kind of demonstrated, I don’t know if this was his intent—that he was not willing to hear the critiques of this new hip-hop generation who had more pointed and perhaps less polished critiques of white supremacy or the existing political systems of oppression that were framed in a more confrontational way. Than the civil rights generation who are still coming from that church and protest politics sort of approach.

And so when I think of the Sister Souljah moment, I think of this new young generation. People who are further being demobilized and disengaged. But that sort of confrontational approach I think does make a comeback in the mid-2010s with the Movement for Black Lives, which is very much a youth-led... I guess it would be the post hip-hop generation, but definitely [a] comeback [of] that same sort of energy.

And, and we see again how... how the Clinton administration—not the Clinton administration, Bill and Hillary Clinton themselves—had to negotiate that energy in new ways where they couldn’t do a Souljah moment anymore.

Bacon: They know they couldn’t do that. They really want[ed] to. So the early 2000s, I think, I’m a ’90s kid too, but I think by the 2000s it is both. When something bad happens in America for Black people, Sharpton or Jesse Jackson—mm-hmm—show up. Sharpton as maybe supplanting him, and if there’s only one Black leader, Sharpton as maybe [the one].

So I want to talk about though Barack Obama coming along, because I think at the time I probably interpreted Jesse Jackson as being envious of Barack Obama when he is criticizing him and so on. That might have been correct, but there may be a difference of political ideology. Did Jesse Jackson recognize Barack Obama’s neoliberal commitments and lack of leftist commitments, maybe more than other people did?

Wiggins: Yeah, I would definitely say that. I mean, that famous hot mic quote where I think I can’t remember where Jesse was being interviewed, but he was caught on a hot mic. I don’t know if I can say this on this live...

Bacon: But you can go ahead and say it for—yeah.

Wiggins: Yeah. It’s... I don’t... something to the effect of: “I don’t like how Barack is talking down to Black people on these faith-based initiatives. It makes me want to cut his...”

Bacon: ...I remember I covered this. Obama, whenever he would go to a Black crowd, would give a sort of speech about how there’s racism. But we need to sort of focus on making sure our kids go to school on time. We don’t throw garbage.

He would never talk about this in a white crowd. In a Black crowd he gave all these sort of, yeah, personal responsibility lectures. That felt annoying if you were a... most people are not throwing garbage out their... out of their houses at the time.. So, and Jesse Jackson responded to that saying Obama should not lecture Black people whenever he’s in front of them.

Wiggins: Yeah. Kind of the “Cousin Pookie” sort of thing.

Bacon: “Cousin Pookie, you need to vote.” Yeah.

Wiggins: Yeah. And so it’s an interesting moment because Jesse Jackson was also engaged in that moralizing disciplinary sort of language. Less so when he ran for president. But if we think about the kinds of speeches he was giving about the problem of ... he’s one of the people that popularizes the idea of Black-on-Black crime. He’s one of the first to use it.

He, you know, would always be decrying “babies making babies” and, you know, have this moralizing approach to Black social problems. He did not do that as a candidate. I think that was the issue that he had with Obama.

Bacon: He thought Obama was doing it. He thought Obama was attacking Black people to win white votes.

Wiggins: Yeah, yeah, that’s what I would say. And that he would only do it to Black people. That he would not do that in front of white audiences. And of course Obama was engaged in this long tradition of castigating poor Black people and their “immoral behavior.”

But I think Jesse Jackson understood that that was not the time and space. That’s not what a presidential candidate, I think, should be doing. That’s not what a Black presidential candidate should be doing. We should be pouring into people and building them up.

And I encourage everyone. to go back and listen to his ’84 Democratic National Convention or his ’88 one. They’re both excellent. But that is not the vision that he was trying to create as a candidate. As a candidate, he was really trying to mobilize and inspire people and, you know, help them understand that they mattered, that they could participate in the political process by supporting Jesse Jackson and that they had a voice.

He wasn’t trying to shoot people down. If he did that outside of his candidacy as the Reverend Jesse Jackson. But as a candidate, he was trying to continue the work of Dr. King and building this, you know, “Beloved Community” that was built on, you know, supporting people and working to create the conditions for them to improve their lives rather than, you know, yelling at them or scolding them for doing the best that they could in the conditions that they were living in, as Obama was doing.

Bacon: Let me finish by talking about the 2010s you made reference to earlier. So in some ways this... this movement of young activist[s] says: We don’t want to have a... we don’t want to have a universal leader. We really don’t want... want to have a... a male universal leader. And we don’t want... and... and we want to have a diffuse movement.

That is a critique of Jesse Jackson and Al Sharpton almost [in a] word that that’s... and, and so yeah, I think that’s what that was going. Right?

Wiggins: Yeah.

Bacon: And so connect Jesse Jackson and Black Lives Matter to me. If you can in any way. Are they in tension with each other? I mean, the movement was not church-based. It’s not pastor-based. It’s not male-led. It’s not single-person-led. But the policy differences are not that. So talk about they’re both critiquing. “Racial capitalism” is a good phrase you used early on. So talk about these movements and where Jesse Jackson and Black Lives Matter.

Wiggins: Yeah, I see Black Lives Matter, the Movement for Black Lives, as sort of a correction of Jesse Jackson’s movement, but an improvement of it. I think that there were Black feminist organizers who were quite critical of the sort of politics of male charisma that Jesse Jackson relied upon.

And I see the Movement for Black Lives as being in the tradition of that Black feminist and queer organizing as well; that they identify similar problems. I do think that they come to similar or different solutions.

I think Jesse Jackson … I would not describe him as “left.” He still believed in the possibility of improving capitalism to work, you know, [in a] less discriminatory way. Whereas I think the Movement for Black Lives is more on the left, but they identify the same problems of “economic violence.”

I think the Movement for Black Lives has developed a fuller critique [based on] and expanded beyond the limitations of Jesse Jackson’s church-based, Black liberal sort of reading of the problems. But I do understand them not necessarily in tension, but maybe in a “productive tension,” I’ll say that.

But they definitely emerged in response to the sort of Black male leader-centered movement politics that had developed since really... I mean, I was about to say since the death of King, but really including that vision of civil rights.

Bacon: A couple things. So there’s a lot of op-ed writing today, and I think we have a good piece in TNR talking about how the ’84 and ’88 campaigns of Jesse Jackson were this kind of economic populism that is coming back. And maybe it should have not been abandoned in the first place.

But your overall picture is that Jesse Jackson was not a leftist social democrat every day of the week. His policy views were more complicated, and some of them were more “liberal Obama-ish” than “Bernie Sanders-like,” is a way to say that. Right?

Wiggins: Yeah. I love thinking about Jesse because he was really quite complicated and he had a vision, but it was limited in ways. Even his movement was limited in ways.

But I do think that the fact that he had a clear moral vision of what is right, what is wrong, who are the enemies of the working class that is far, far more productive than a lot of the sort of politics or the approach of Democrats in the present day.

So even if he wasn’t to the left and he wanted to, you know, reform capitalism and make it more democratic than other people that were to the left of him ... he still, on the spectrum that we currently have … he is still quite radical. And his ’84 and ’88 platforms would be reviving some of those ideas, would be a step in the right direction for today’s Democrats.

Bacon: My final question is not about Jesse Jackson in some ways, but you’re a historian. If we have a “Long Black Freedom Movement,” talk about 2014 to 2025. Do we have a movement of Black Lives that ended it, or it’s continuing?

We’re not having the mass protests. We had a period of mass protests; we don’t have them now. People ask me all the time: What happened to Black Lives Matter? And it’s tricky. ’Cause I think a lot of those people are, like, working on Zohran’s campaign or working for the Working Families Party… they are doing stuff. But how do you see Black activism today, thinking about the history that you study?

Wiggins: Yeah, it’s hard for me to answer that question without acknowledging the ways in which Black radical activism in particular is being policed and suppressed. I’m a scholar of Atlanta. I’ve been keeping up with the protests to stop the construction of the police training facility or what is referred to as “Cop City.”

Bacon: “Cop City.” OK. Sorry.

Wiggins: “Cop City.” If we take that as a case, they’re throwing RICO charges at them and domestic terrorism charges. So I think it’s important to foreground the counterinsurgent measures that we’ve seen. You know, not even before Trump came back into office, but really since 2020, 2021.

So this is a moment, perhaps, where Black activists needing to reimagine and reframe what the movement looks like in a “mask off” fascist state. To put it crudely, I think the counterinsurgency has been intensified. And so that is shaping what the future will look like.

Bacon: I’m still a little skeptical of this idea of “leaderless” movements, but is there “leader-full”? I’ve never been on board with that. But what’s your thought about that?

Because Jesse Jackson is a product of the “there must be three or four identified people that speak for Black folks” era. And we’re now in an era where we’re trying to avoid that. And at times I do want Sherrilyn Ifill to be appointed to be the leader of Black people.

And we go to her. Somebody who is smart and thoughtful and respected. There are moments where I don’t want it to be a man, but I wish it was somebody.

Wiggins: I don’t know. I’m a historian, so I’m always thinking about history in the past and this group-centered leadership paradigm that’s articulated by folks like Ella Baker.

There is an opportunity to maybe return to those foundational ideas about what leadership should look like, because you’re right that a completely “leaderless” movement … it makes it difficult to organize on a national or even regional scale. At the same time, we know very well the limits of a charismatic leader–led movement. So I do think that there is kind of a “Third Way” or a middle ground.

Bacon: We’re not for “Third Ways” except for this. OK. Right.

Wiggins: This one “Third Way” is OK. That is grounded in those Black organizing traditions. Group-centered leadership, participatory democracy. The way that Black labor unions were organizing in the 1940s, ’50s, and ’60s as well.

Now is a time to return to the elders. Talk to the elders while they’re still here, and resuscitate some of those practices because they face the same issues. Right?

Bacon: Sure.

Wiggins: The student activists of SNCC were also very critical of having this Martin Luther King as the face of the movement.

Bacon: Sure. Yeah.

Wiggins: Called “De Lawd,” as Stokely Carmichael would say. And so people have been thinking through these aren’t new ideas. So it’s a good moment to return to that moment because it’s also a moment of repression as well. So there’s a lot that we can gain from engaging with those older debates about who and how to lead.

Bacon: Danielle, this is great. I appreciate it. Drink some water now. Went over my time, and thank you. A great book, and I want to encourage you to read—Danielle has a book out called Black Excellence. It talks about the post–civil rights struggles in Atlanta, but also throughout the country. Again, Black Excellence. Danielle Wiggins is a professor at Georgetown. Thanks for joining me. Thanks everyone who came on. Bye-bye.

Wiggins: Thank you.