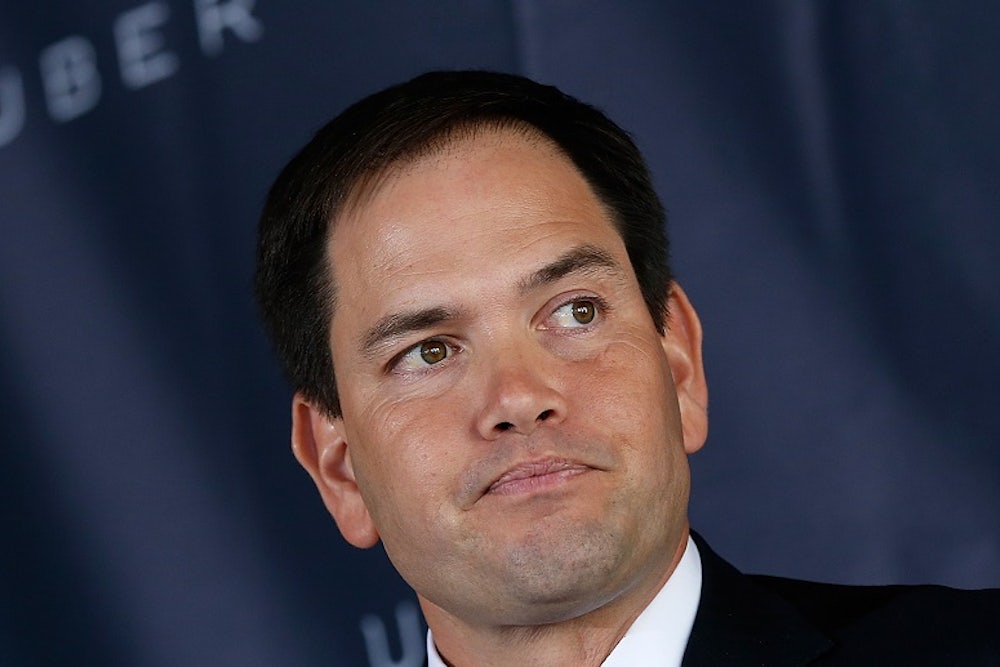

In the past two months, I’ve criticized Senator Marco Rubio twice on his antipoverty agenda. Some have complained that I mischaracterized Rubio’s plan as requiring a benefit cut for working parents. Ultimately, I stand by that conclusion, but Rubio’s antipoverty agenda is both more complicated than I explained and represents a rampant problem in Republican policy proposals.

Rubio’s proposal builds on an idea from Oren Cass, a former adviser to Mitt Romney. Cass, who outlined the plan in an article for National Review, wants to redesign the federal government’s antipoverty programs in two ways. First, he wants to separate the benefits that working adults and non-working adults collect. Right now, some working, low-income adults collect benefits from the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), housing assistance, and a host of other programs. Only working adults receive benefits from the Earned Income Tax Credit. Cass’s plan consolidates all benefits that working adults collect into a wage subsidy—extra, government-funded money that increases wages.

Right now, working parents benefit significantly more than childless, working adults from government antipoverty programs—especially the EITC. Cass’s plan equalizes that, but since the total amount of resources is unchanged, parents would have to face a benefit cut. “[B]y default, under the proposal as I described it, benefits within the 'working adult' segment get reallocated toward non-parents,” Cass said in an email.

Ultimately, since Cass is keeping the total money that working adults receive unchanged, any increased benefits for childless, working adults must come from working parents. There’s no way around the math. Cass says as much in admitting that his proposal would cause benefits to be “reallocated toward non-parents.” Alternatively, he could say that benefits would be reallocated away from parents.

The second part of Cass’s plan is to turn the remaining government antipoverty funding into a Flex Fund that would distribute the money to the states. In National Review¸ Cass explained that the “funding formula would be pegged to the size of the population in need and would grow at the same rate as the poverty threshold itself.” The states would be free to design new programs to try to deliver benefits more efficiently or they could continue with the current system.

This plan has a couple of smart features, like transitioning the EITC and a few other programs to a wage subsidy so that the benefits are delivered monthly or biweekly instead of annually. It also has some more worrisome ones. Cass would require states to spend the Flex Fund money on antipoverty programs, but many liberals are concerned that this would not work in practice. (Conservatives worry about the opposite of this as well.)

Regardless of those features (or flaws), Rubio’s proposal immediately fails the smell test. In a January address announcing the plan, Rubio said, “Unlike the earned income tax credit, my proposal would apply the same to singles as it would to married couples and families with children.” While Rubio does not say it explicitly, his press secretary, Alex Conant, confirmed to me that the goal of the plan is to increase benefits for childless working adults via the wage subsidy, without decreasing them for working parents. And the whole thing would be deficit neutral.

That’s mathematically impossible—as under Cass’s plan, any increase in benefits for working non-parents necessitates a reduction in benefits for working parents. Ultimately, Rubio’s office expects the plan to create long-term savings, which, if they happen, could ensure that childless, working adults collect more in benefits without reducing those collected by working parents. But that is years down the line. “We anticipate long-term savings, but that’s not the purpose of the reforms and in the short-term, we don’t anticipate savings,” Conant told me. “As we said, in the short-term, we expect it to be deficit-neutral.”

Conant argued that it’s “premature to be pointing out winners and losers since we’re still developing the policy,” but that’s exactly what Rubio did in his January speech. The senator specified that childless, working adults would be winners, but refused to admit that the losers would be working parents. In doing so, he became yet another Republican to set policy goals that he cannot meet.