Happy news, Mike Nichols’ second film, The Graduate, proves that he is a genuine film director—one to be admired and concerned about. It also marks the screen debut, in the title role, of Dustin Hoffman, a young actor already known in the theater as an exceptional talent, who here increases his reputation. Also, after many months of prattle about the “new” American film (mostly occasioned by the overrated Bonnie and Clyde), The Graduate gives some substance to the contention that American films are coming of age—of our age.

The screenplay, based on a novel by Charles Webb, was written by Calder Willingham and Buck Henry. The latter, like Nichols, is an experienced satiric performer. (Henry appears in this picture as a hotel clerk.) The dialogue is sharp, hip without rupturing itself in the effort, often moving, and frequently funny except for a few obtrusive gag lines. The story is about a young cop-out who—for well-dramatized reasons—cops at least partially in again.

Ben is a bright college graduate who returns to his wealthy parents’ Hollywood home and flops—on his bed, on the rubber raft in the pool. Politely and dispassionately, he declines the options thrust at him by barbecue-pit society. The bored wife of his father’s law partner seduces him. Ben is increasingly uncomfortable in the continuing affair, for moral reasons of an unpuritanical kind. (The bedroom scene in which Ben tries to get her to talk to him is a jewel.) The woman’s daughter comes home from college, and against the mother’s wishes, Ben takes her out. He falls in love with the girl—which is predictable but entirely credible. He is blackmailed into telling her about his affair with her mother and, in revulsion, the girl flees—back to Berkeley. Ben follows, hangs about the campus, almost gets her to marry him, loses her (through her father’s interference), pursues her, and finally gets here. For once, a happy ending makes us feel happy.

To dispose at once of the tedious subject of frankness, I note that some of the language and bedroom details push that frontier (in American films) considerably ahead, but it is all so appropriate that it never has the slightest smack of daring, let alone opportunism. What is truly daring, and therefore refreshing, is the film’s moral stance. Its acceptance of the fact that a young man might have an affair with a woman and still marry her daughter (a situation not exactly unheard of in America although not previously seen in American films) is part of the film’s fundamental insistence: that life, today, in our world, is not worth living unless one can prove it day-by-day, by values that ring true day-by-day.

Moral attitudes, far from relaxing, are getting stricter and stricter, and many of the shoddy moralistic acceptances that dictated mindless actions for decades are now being fiercely questioned. Ben is neither a laggard nor a lecher; he is, in the healthiest sense, a moralist—he wants to know the value of what he is doing. He does not rush into the affair with the mother out of any social rote of “scoring” any more than he avoids the daughter—because he has slept with her mother—out of any social rote of taboo. (In fact, although he is male and eventually succumbs, he sees the older woman’s advances as a syndrome of a suspect society.) And the sexual dynamics of the story propels Ben past the sexual sphere; it forces him to assess and locate himself in every aspect.

Sheerly in terms of moral revolution, all this will seem pretty commonplace to readers of contemporary American fiction. But we are dealing here with an art form that, because of its capable broad-based appeal, follows well behind the front lines of moral exploration. In America it follows less closely than in some other countries, not because American audiences are necessarily less sophisticated than others (although they are less sophisticated than, say, Swedish audiences) but because the great expense of American production encourages a producer to cast the widest not possible. None of this is an apology for the film medium, it is a fact of the film’s existence; one might as sensibly apologize for painting because it cannot be seen simultaneously by millions the way a film can. Thus the arrival of The Graduate can be viewed two ways.

First, it is an index of moral change in a substantial segment of the American public, at least of an awakening of some doubts about past acceptances. Second, it is irrelevant that these changes are arriving in film a decade or two decades or a half century after the other arts, because their statement in film makes them intrinsically new and unique. If arts have textural differences and are not simply different envelopes for the same contents, then the way in which The Graduate affects us makes it quite a different work from the original novel (which I have not read) and from all the dozens of novels of moral disruption and exploration in recent years. Recently an Italian literary critic and teacher deplored to me the adulation of young people for films, saying that the “messages” they get from Bergman and Antonioni and Godard were stated by the novel and even the drama thirty or forty years ago. I tried (unsuccessfully) to point out that this is not really true: that if art as art has any validity at all, then the film’s peculiar sensory avenues were giving those “old” insights a being they could not otherwise have.

This brings us to the central artist of this enterprise, Mike Nichols. In his first picture Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, Nichols was shackled by a famous play and by the two powerhouse stars of our time; but considering these handicaps, he did a creditable job, particularly with his actors. In The Graduate, uninhibited by the need to reproduce a Broadway hit and with freedom to select his cast, he has moved fully into film. He is perceptive, imaginative, witty; he has a shrewd eye, both for beauty and for visual comment; he knows how to compose and to juxtapose; he has an innate sense of the manifold ways in which film can be better than he is and therefore how good he can be through it—including the powers of expansion and ellipsis.

From the very first moment, Nichols sets the key. We see Ben’s face, large and absolutely alone. The camera pulls back, we see that he is in an airliner and a voice tells us that it is approaching Los Angeles; but Ben has been set for us as alone. We follow him through the air terminal, and he seems just as completely, even comfortably isolated in the crowd as he does later, in a scuba suit at the bottom of his family’s swimming-pool, when he is huddling contentedly in an underwater corner while his twenty-first birthday party is being bulled along by his father up above.

Nichols understands sound. The device of overlapping is somewhat overused (beginning the dialogue of the next scene under the end of the present scene), but in general this effect adds to the dissolution of clock time, creating a more subjective time. Nichols’ use of non-verbal sound (something like Antonioni’s) does a good deal to fix subliminally the cultural locus. For instance, a jet plane swooshes overhead—unremarked—as the married woman first invites Ben into her house.

In Virginia Woolf I thought I saw some influence of Kurosawa; I think so again here, particularly in such sequences as Ben’s welcome-home party where the camera keeps close to Ben, panning with him as he weaves through the crowd, moving to another face only when Ben encounters it, as if Ben’s attention controlled the camera’s. As with Kurosawa, the effect is balletic; it seeks out quintessential rhythms in commonplace actions.

On the negative side, I disliked Nichols’ recurrent affection for the splatter of headlights and sunspots on his lens; and his hang-up with a slightly heavy Godardian irony through objects. (The camera holds on a third-rate painting of a clown after the mistress walks out of the shot. When the girls leaves Ben in front of the monkey cage at the San Francisco zoo, the camera, too luckily, catches the sign on the cage: Do Not Tease.) And a couple of times Nichols puts his camera in places that merely make us aware of his cleverness in putting it there: inside the scuba helmet, inside an empty hotel-room closet looking past the hangers.

But the influences I have cited (there are others) only show that Nichols is alive, hungry, properly ambitious; the defects only show that he is not yet entirely sure of himself. Together, these matters show him still feeling his way toward a whole style of his own. What is important is his extraordinary basic talent: humane, deft, exuberant. And I want to make much of his ability to direct actors, a factor generally overlooked in appraising film directors. (Some famous directors—Hitchcock, for example—can do nothing with actors. They get what the actor can supply on his own. Sometimes—again like Hitchcock—these directors are not even aware of bad performances.) He has helped Anne Bancroft to a quiet, strong portrayal of the mistress, bitter and pitiful. With acuteness he has cast Elizabeth Wilson, a sensitive comedienne, as Ben’s mother. From the very pretty Katharine Ross, Ben’s girl, Nichols’ has got a performance of sweetness, dignity, and a compassion that is simply engulfing. Only William Daniels, as Ben’s father, made me a bit uneasy. His WASP caricature (he did a younger version in Two for the Road) is already becoming a staple item.

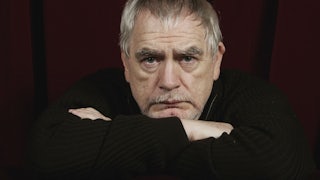

In the leading role, Nichols had the sense and the courage to cast Dustin Hoffman, unknown (to the screen) and unhandsome. Hoffman’s face in itself is a proof of change in American films; it is hard to imagine him in leading roles a decade ago. How unimportant, how interesting this quickly becomes, because Hoffman is one of the best actors of his generation, subtle, vital, and accurate. Certainly he is the best American film comedian since Jack Lemmon, and, as theatergoers know, he has a much wider range than Lemmon. (For instance, he was fine as a crabby, fortyish, 19th-century Russian clerk in Ronald Ribman’s play Journey of the Fifth Horse.)

With tact and lovely understanding, Nichols and Hoffman and Miss Ross—all three—show us how this boy and girl fall into a new kind of love: a love based on recognition of identical loneliness on their side of a generational gap, a gap which—never mind how sillily it is often exploited in politics and pop culture—irrefutably exists. When her father is, understandably, enraged at the news of his wife’s affair with his prospective son-in-law and hustles the girl off into another marriage, Ben’s almost insane refusal to let her go is his refusal to let go of the one reality he has found in a world that otherwise exists behind a pane of glass.

The cinema metaphors of the chase after the girl—the endless driving, the jumping in and out of his sports car, even his eventual running out of gas—have perhaps too much Keaton about them; they make the film rise too close to the surface of mere physicality; but at least the urgency never flags. At the wedding, when he finds it—and of course it is in an ultra-modern church—there is a dubious hint of crucifixion as Ben flings his outspread arms against the (literal) pane of glass that separates him from life (the girl); but this is redeemed a minute later when, with the girl, he grabs a large cross, swings it savagely to stave off pursuers, then jams it through the handles of the front doors to lock the crowd in behind them.

The pair jump on to a passing bus (she in her wedding dress still) and sit in the back. The aged, uncomprehending passengers turn and stare at them. (One last reminder!—of Lester’s old-folks chorus in The Knack.) Ben and his girl sit next to each other, breathing hard, not even laughing, just happy. Nothing is solved—none of the things that bother Ben—by the fact of their being together; but, for him, nothing would be worth solving without her. We know that and she knows that, and all of us feel very, very good. The chase and the last-minute rescue (just after the ceremony is finished) are contrivances, but they are contrivances tending toward truth, not falsity, which may be one definition of good art.

Paul Simon has written rock songs for the film, sung by Simon and Garfunkel, and as in many rock songs, these lyrics deal easily with such matters as God, Angst, the “sound of silence,” and social revision. But they are typical of the musical environment in which this boy and girl live.

Some elements of slickness and shininess in this wide-screen, color film are disturbing. But despite them, despite the evident influences and defects, the picture bears the imprint of a man, a whole man, warts and all: which is a very different imprint from that of many of Nichols’ highly praised, cagy, compromised American contemporaries. All the talents involved in The Graduate make it soar brightly above its shortcomings and, for reasons given, make it a milestone in American film history. Milestones do not guarantee that everything after them will be better, still they are ineradicable.