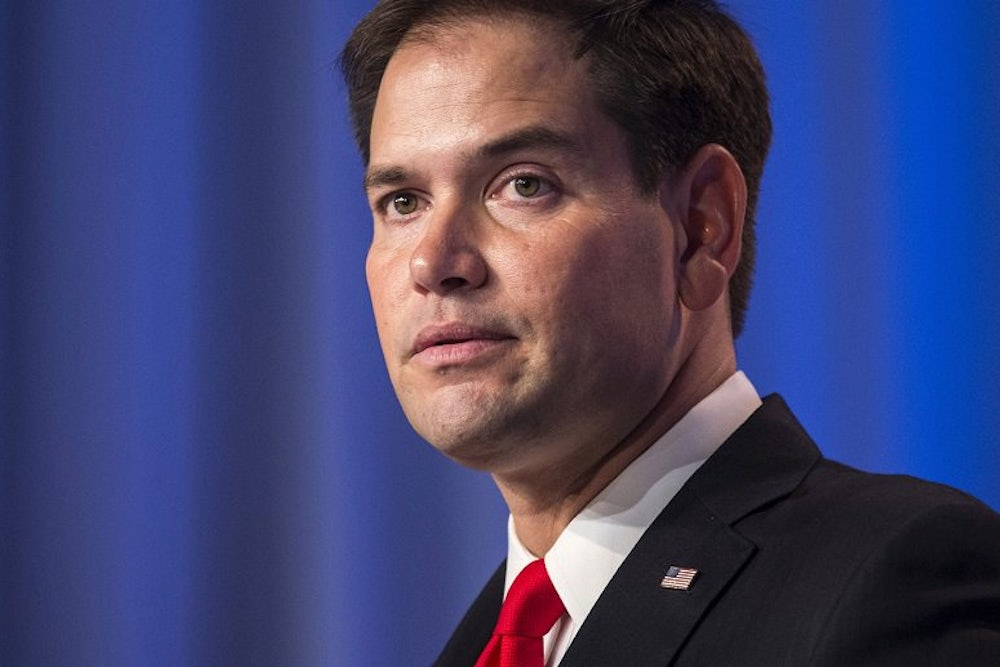

On Monday in Miami, Senator Marco Rubio will announce that he’s running for president. And unlike his Senate colleagues Rand Paul and Ted Cruz, he has a legitimate chance of winning. By all accounts, Rubio has succeeded in the invisible primary, winning over donors and hiring seasoned campaign operatives in key primary states. He has a sympathetic back story and is an excellent public speaker. But what endears him to many Republican Party elites is his brand of conservatism that focuses on big solutions to the 21st century problems in the United States.

Throughout President Barack Obama's presidency, Republican policymakers have been rightfully criticized by liberals as unserious. Their economic agenda is a farce and they keep promising a plan to replace Obamacare without ever delivering one. For many on the right, Rubio—with a new book chock full of policy ideas—is the answer to these criticisms.

Some of those ideas are genuinely good. Others are updates of the same old Republican orthodoxy—fresh rhetoric for stale policy. Some, like The New Republic's Brian Beutler, look at Rubio's proposals and conclude he is a fraud—that he is trying to fool centrists and center-left liberals into supporting a disguised version of traditional Republican policies. I propose another possibility: that Rubio earnestly wants to put forth conservative policy solutions to fix our tax system and improve the lives of poor Americans. The problem is, he must tailor these solutions to gain substantial support in the GOP, and those compromises would cause more harm to the poor.

That's the generous interpretation, anyway—but the one I took in evaluating his proposals on taxes, welfare, and immigration.

Rubio Is Not Afraid of Deficit Hawks

In crafting their tax plan, Rubio and Senator Mike Lee had to choose two of the following: cut marginal tax rates, expand the Child Tax Credit (CTC), and keep the plan deficit-neutral. They selected the first two and dropped any pretense that the plan would be deficit-neutral. Using a static score, the Tax Foundation estimated the Rubio-Leeplan would lose $4 trillion over the next decade. In an age of rising inequality and aging demographics, the plan, which is also very regressive, is wildly unrealistic. The benefits accrue predominantly to the people who need them least and it fails to account for the real reasons our spending is projected to rise significantly in the next few decades. In other words, if Rubio is such a wonk, this is not the plan he would’ve devised.

But maybe Rubio crafted the plan to appeal to mainstream Republicans who have repeatedly criticized the CTC expansion. Perhaps that's too lenient for a cold-hearted plan, but it’s not implausible. If Rubio and Lee had proposed a deficit-neutral tax reform with a big CTC expansion, they would have had little ability to cut marginal tax rates—and no ability to sell the plan to the GOP. In that telling, Rubio compromised on deficit-neutrality to garner support for the CTC expansion. (Even so, may on the right still oppose it.) That doesn’t make his plan any better, of course, but it makes it more understandable.

Rubio’s Fuzzy Math on Welfare Reform

In January, 2014, Rubio revealed a proposal to dramatically reform the federal government’s antipoverty system in two ways. First, it would convert the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) into a similar program called a wage subsidy and expand it so that childless, working adults could benefit from it as well. (The current EITC provides almost no benefits for childless, working adults.) Second, the proposal would combine dozens of antipoverty programs into one “Flex Fund,” which would then give money to states in lump sum payments.

Rubio claims that antipoverty spending will stay flat in his plan. That’s not possible. If he intends to increase payments to childless, working adults—a good idea—that money has to come from somewhere. Rubio’s staff has never given me a clear answer about the funding source of the proposal, and when he went on “The Daily Show” to promote his book, he sidestepped questions from Jon Stewart about the funding source multiple times. Even the architect of the “Flex Fund” idea, Oren Cass, a former adviser to Mitt Romney, told me in an email last April that “by default, under the proposal as I described it, benefits within the 'working adult' segment get reallocated toward non-parents.”

Why is Rubio promoting a plan that is mathematically impossible? Politics. Turns out, increasing antipoverty spending isn’t a very popular position in the Republican Party. But expanding the EITC (in the form of a wage subsidy) to include childless, working adults is popular among conservatives because the program promotes work. Finding money to fund that expansion is difficult, though. If you take it from other parts of antipoverty spending, you’ll be criticized for hurting poor people. And there’s no way Rubio could forego a spending offset or, God forbid, raise revenue. Instead, he decided to ignore the problem altogether.

Immigration Reform: Rubio's Moving Target

Rubio may be most well-known in the public for his support for the Senate immigration reform plan in the 113th Congress and the subsequent freak out conservatives had over it. Before he supported a pathway to citizenship, Rubio was considered a leading candidate for the Republican nomination in 2016. Afterwards, many political analysts wrote him off entirely.

But recently, Rubio has attempted to mend fissures with the conservative base while continuing to show compassion for undocumented immigrants in the U.S. He disavowed his previous position on immigration and now believes that any changes to U.S. immigration policy cannot come until the federal government achieves certain unspecified metrics on border security. Beyond that, he also wants to convert the current immigration system from family-based to merit-based. Undocumented immigrants could apply for temporary nonimmigrant status after undergoing a background test, learning English and paying a fee. After a decade, they could apply for permanent residency.

What Rubio doesn’t say in his book is that permanent residency eventually allows undocumented immigrants to apply for citizenship. Rubio admits as much in an interview with The New York Times. In other words, his new plan includes a path to citizenship. That’s not how Rubio describes the plan in his book, where he even says that undocumented immigrants wouldn’t have “any special pathway” to permanent residency.

Rubio is dancing with conservatives here. He understands that the GOP must have some plan besides “self-deportation” for the 11 million undocumented immigrants living in the U.S. But he also learned firsthand that explicitly proposing a pathway to citizenship is unacceptable in today’s GOP. So instead he downplayed that part of his plan and focuses on the need for strong border metrics. Politics demanded it.

Rubio isn’t the most well-known Republican wonk that many on the left consider a fraud. That honor goes to Representative Paul Ryan, who often speaks about trying to help the poor while his budgets, if implemented, would have been disastrous for low-income Americans.

Yet the same generous interpretation that I applied to Rubio can be applied to Ryan. In order to stay relevant within the Republican Party, he had to propose massive spending cuts—cuts that Ryan himself didn't believe in. This isn’t just my theory. New York Times columnist Ross Douthat wrote last year:

Now without claiming special knowledge, my sense is that Ryan himself might accept some of the merits of the first critique [that his budget cuts too much from antipoverty programs], and that his budget’s implausible discretionary cuts were mostly driven by the political imperative to 1) meet the House conservative demand for a balanced budget as soon as humanly possible (in ten … no, five years!) without 2) including any kind of Social Security overhaul. While there isn’t (yet) a Ryan blueprint specifically focused on safety-net reform, if you look at some of his post-2012 forays on the issue, you can see the outline (in this op-ed, for instance) of a more plausible approach, in which the focus is on reshaping antipoverty programs rather than just slashing them to achieve unlikely spending targets.

Three weeks later, Ryan released his own antipoverty plan that was incompatible with his past budgets. But this inconsistency didn’t stop Douthat from praising the antipoverty plan by saying it “basically eliminates the daylight that existed between ‘Ryanism’ and reform conservatism on safety net reform.” In order to credit Ryan for this new plan, though, you have to assume that he didn’t actually believe what was in the Ryan budgets, or at least has significantly evolved on the issue in the past year. Rubio is hoping for a similarly generous interpretation of his policy agenda—that the negative components of it are there out of political necessity and will be quickly forgotten.

This interpretation is flawed for three reasons. First, journalists can’t read the minds of candidates. Maybe Rubio really does support a massive tax cut and I’m giving him too much credit by suggesting he could be acquiescing to it for political reasons. Second, even if Rubio is changing his proposals for political reasons, political science research tells us that candidates actually stick to their promises. If Rubio proposes a big tax cut, it’s more than likely that he’ll try to pass a big tax cut if he wins the presidency. That means, ultimately, Rubio’s ideal plan—the one unconstrained by politics—doesn’t matter that much. Journalists should assume that Rubio’s platform represents his policy agenda if he wins the White House.

Most importantly, to downplay the negative features of Ryan’s budgets and Rubio’s tax proposals is to excuse their bad ideas. Ryan is free to denigrate the poor and Rubio can promise further tax cuts for the rich when the political situation suits them—and face no consequences for doing so. Ultimately, this eliminates accountability from our political system.

It's tempting to overlook those reasons and give Rubio the benefit of the doubt. After all, it's not easy to be a wonk in a Republican Party that's hostile to unorthodox ideas. Rubio is at least trying to push his party in the right direction. But journalists and policy analysts cannot ignore the implications of Rubio's agenda, as conservatives have sometimes done with Ryan. We must judge Rubio’s policy platform—in its entirety—on its own merits.