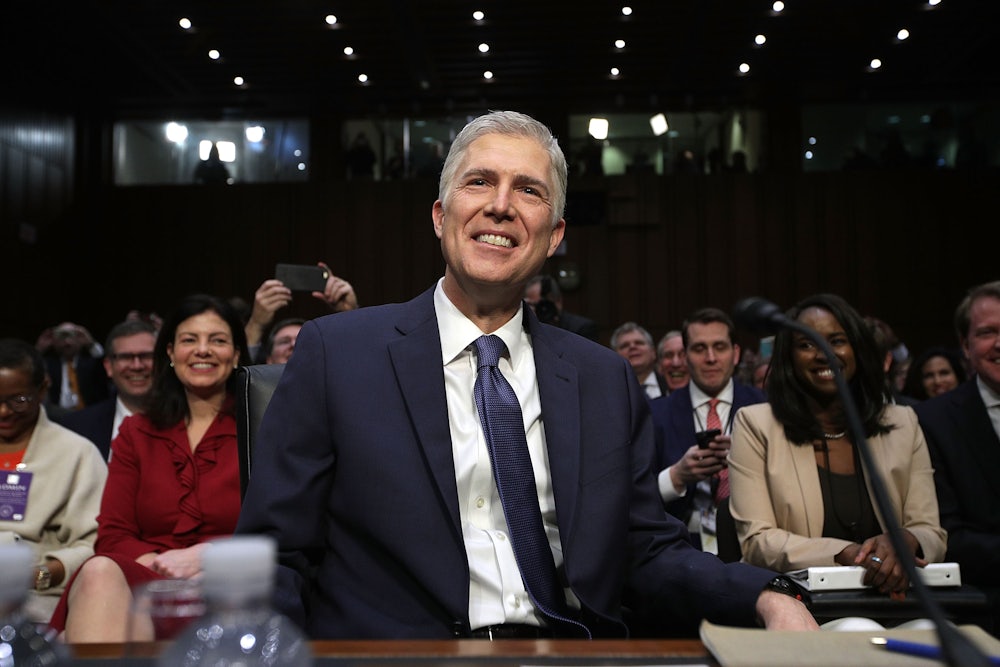

Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell has changed the Supreme Court for good. On Thursday, Democrats successfully filibustered President Donald Trump’s nomination of Neil Gorsuch, the 49-year-old arch-conservative from the Tenth Circuit Court of Appeals in Denver, Colorado. Senate Republicans responded by changing the rules to require only a simple majority to confirm Supreme Court nominees, which was already the rule for all other federal judicial appointments. The immediate outcome was bad: Gorsuch was confirmed to a lifetime appointment to the Court on Friday. In the long term, the battle over Gorsuch reflects a new era in which Senate deference to judicial nominations is over, possibly with more sea changes to come.

We should be clear that Senate Democrats did the right thing by filibustering Gorsuch. If a simple majority for Supreme Court nominations is going to be the new norm—and it clearly is—it is better that this be done explicitly and immediately. Democrats had absolutely nothing to gain by pretending that the previous norms held, particularly after the refusal of Republicans to consider former President Barack Obama’s nominee Merrick Garland to replace Antonin Scalia. It was guaranteed that Republicans would nuke the filibuster for another Republican nominee—or exploit the filibuster for a Democratic one.

The end of the filibuster was the culmination of a long process. Republicans are inclined to blame the defeat of Robert Bork by a Democratic Senate in 1987, but this is misleading—Bork was given a full up-or-down vote, and after he was rejected the Senate quickly confirmed a more moderate nominee, Anthony Kennedy. The Bork nomination did not destroy the norm of deference to the president’s choice for the Supreme Court.

Rather, what contributed to a culture of obstruction was the rejection of lower-court nominees, which began with Republicans under Bill Clinton, escalated with Democrats under George W. Bush, and escalated even further with the Republican minority under Obama. The key was the failure of the so-called “Gang of 14” deal under Bush that allowed a large number of Bush nominees—including some genuine extremists like Judge Janice Rogers Brown—to be seated. It preserved the filibuster for judicial nominees with a promise to use it only in “extraordinary circumstances.” But as soon as Obama was elected these circumstances turned out to be “any nominee Republicans don’t like, regardless of their qualifications.”

Senate Republicans refused to consider any Obama nominee to the nation’s second-most powerful court, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit, because it would have changed the balance of power on the court. Harry Reid, then the Senate majority leader, was compelled in 2013 to use the nuclear option to eliminate the filibuster for non-Supreme Court judicial appointments. This made the elimination of the filibuster for Supreme Court nominations all but inevitable. The way a Republican majority treated Obama’s nomination to replace Scalia ensured that the showdown would happen quickly.

Even Democratic senators who were committed to prior norms of senatorial deference couldn’t ignore that this Supreme Court seat was available to Trump because Republicans had stolen it. Furthermore, Trump’s nominee was about as far from a consensus nominee as you could get, a sop to the hard right. The new norm is that judicial nominations will be treated as a partisan issue, not significantly different than legislation. Opposition lawmakers no longer owe deference to the president’s nominees.

One response to this new state of affairs is to pine for the old order. Ruth Marcus of the Washington Post, for example, argues that Senate Democrats should have allowed “an up-or-down vote now, in exchange for a promise not to abolish the filibuster next time.” But this deal would be transparently worthless even if McConnell offered it. Anyone who thinks that McConnell would allow the Democrats to filibuster a Supreme Court nomination—especially a nomination that would transform the median vote of the Court—because of an inherently unenforceable promise should invest their life savings in a doctorate from Trump University.

And yet, I can understand the nostalgia for the previous ways of doing business. The new, partisan norms are likely to get ugly, especially during times of divided government. And other longstanding norms might also be threatened.

One implication of the new normal is that we’re likely looking at a future in which presidents can only reliably fill judicial vacancies when their party is in control of the Senate. Supreme Court vacancies will be impossible to fill when the Senate is in opposition hands. Had Hillary Clinton won with a Republican Senate, it is overwhelmingly likely that the Republican blockade would have continued unless Democrats retook the Senate in 2018. McConnell proved that obstruction doesn’t carry a political cost, and opposition parties have no incentive to give high-stakes victories to the president.

One upshot of this is that short-handed Supreme Courts will become increasingly common. This isn’t the end of the world; some issues can be resolved by an eight-member Court. In a federal system, circuit splits are suboptimal but not necessarily disastrous. The American separation-of-powers structure produces many inefficiencies, for better or worse, and this will be another one.

The nuclear option could portend further norms going by the wayside, however. The nine-member Supreme Court is not fixed by the Constitution, but is simply a norm that has now persisted for more than a century. If Gorsuch is the last first-term Trump nominee to be confirmed, this norm is likely to persist.

But imagine if Donald Trump is able to replace Anthony Kennedy and Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Stephen Breyer. If the size of the Supreme Court remained at nine, very conservative Republicans would have a stranglehold on the Supreme Court for decades despite the party having lost the popular vote in six of the last seven presidential elections. Furthermore, the decisive appointments would have been made by a historically unpopular president who most voters rejected. Democratic governments would be consistently frustrated when trying to enact their agenda by hostile courts. Cherished rights like a woman’s right to have an abortion would be abandoned.

If this happens, it is very possible that we would have a constitutional crisis. Democrats would likely attempt what FDR tried to do after winning re-election in 1936. Court-packing, as Senate Democrats in 1937 realized, is a far from perfect solution because once the nine-justice equilibrium is gone, the other side will respond in kind when they have the chance, creating a chaotic and increasingly illegitimate judicial system. But a governing coalition facing hostile courts that cannot be quickly transformed may well see it as the least worse option.

The Gorusch filibuster reflects a long-term change in how Supreme Court justices are confirmed. How far-reaching these changes end up being will depend on contingent future events. But there’s no point wishing that the partisan genie can be put back in the bottle. Once norms that conflict with partisan self-interest are gone, they’re nearly impossible to restore. Senate Democrats can’t change this by unilaterally disarming.