Everything the climate movement has accomplished over the past decade is on the chopping block, or so it seems lately. In less than three months, President Donald Trump has reopened coal mining on federal lands and begun unraveling America’s regulations to slow global warming, thereby endangering the country’s climate commitments in the Paris Agreement. He put climate change denier Scott Pruitt in charge of the Environmental Protection Agency—then proposed slashing the agency’s budget and eliminating federal climate change research altogether. Trump is expected soon to reopen portions of the Atlantic and Arctic oceans to oil drilling. What’s an environmentalist to do?

Some have turned to despair. There are even support groups, modeled after Alcoholic Anonymous, for those who worry about the fate of the planet under Trump. Since his election, I’ve heard experienced climate activists utter questions that a year ago would have been unthinkable: Have we lost? Should we give up?

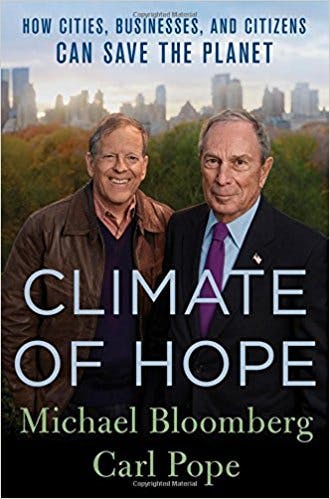

Absolutely not, Michael Bloomberg and Carl Pope argue in their new book, Climate of Hope. As they did in a recent New York Times op-ed, “Climate Progress, With or Without Trump,” the former New York City mayor and former Sierra Club director make a tempting case: We don’t need the president, or even the federal government, to win the climate fight. “Cities are actually the key to saving the planet,” Bloomberg writes. In another chapter, he argues, “The more that business leaders and political leaders see climate change as an economic issue, not just an environmental one, the more progress we’ll make—and the better off our economy will be.” His thesis: “America’s ability to meet our climate pledge doesn’t depend on Washington.”

Bloomberg and Pope’s timing is impeccable, as environmentalists are in desperate need of this book’s optimism. It’s reassuring to imagine that, although the president believes global warming is a “hoax” created by the Chinese, cities and businesses alone can help America meet its climate obligations. And Bloomberg speaks from a position of authority. Not only was he a successful mayor of America’s largest city, but he’s also a plutocrat—just like the president, except vastly richer. Bloomberg understands both local government and big business, and thus, he can make a far more convincing case for the economic benefits of green policies than an environmentalist can.

But for all these positives, Climate of Hope falls short. Under President Barack Obama, despite his aggressive approach to climate change, the U.S. still wasn’t doing enough to meet its emissions reductions targets; Trump is pushing those targets further out of reach. While Climate of Hope lists various initiatives that cities and businesses can take, it doesn’t explain how these ideas comprise a comprehensive plan to reduce global warming before it’s too late.

Perhaps that’s because such a plan can only come from one place. In arguing for local solutions to climate change, Bloomberg and Pope inadvertently make a convincing case for why the federal government is our best hope.

Bloomberg has been pushing for local climate action for years. He’s the president of C40, a climate-friendly collaboration among 90 city leaders (Bloomberg Philanthropies is a key funder). He serves as the U.N. Secretary General’s Special Envoy for Cities and Climate Change, which helps mobilize climate action among cities. And in 2013, he joined forces with fellow billionaire Tom Steyer to launch Risky Business, a comprehensive look at how climate change can negatively impact corporate profits.

But in Climate of Hope, Bloomberg’s most convincing credential is his time as New York City mayor. In 2007, he launched PlaNYC, an ambitious program to lower the city’s emissions and build resilience to climate change’s impacts by 2030. It called for familiar solutions like expanded bike lanes, but also wonky measures like energy retrofits. “Improving the efficiency of buildings is not as sexy as saving a rain forest,” Bloomberg concedes. “But the fact is, making the biggest possible dent in greenhouse gas emissions—and in the pollution that causes death and disease—requires focusing on buildings.” That’s partly why New York City is on track to meet its climate goals.

But New York is more progressive than most American cities, and even ambitious mayors are often hampered by their state governments—something Bloomberg acknowledges by citing his own experience. He details how New York’s Democratic-controlled legislature refused to allow the city to use congestion pricing (a toll system that charges drivers more during rush hour, thereby discouraging car usage and lowering pollution). “Regional and national legislatures often have political interests that cities don’t share,” he writes. If Bloomberg ran into trouble in New York, imagine how innovative green mayors would fare in less progressive states. Will Florida’s climate-denying Governor Rick Scott and his Republican-controlled legislature allow cities to implement aggressive policies to reduce pollution and prepare for rising seas? “A state of denial can be a city’s worst enemy,” Bloomberg writes. He’s correct—but how do we fix that?

Pope raises an important question: “It’s important to know if the individual solutions we are implementing, when added up, are likely to restore a stable climate.” In other words: Exactly how much do cities need to reduce emissions in order for the U.S. to meet its obligations under the Paris Agreement? Climate of Hope, as wonky as it is, never attempts an answer. According to Vox, America must cut carbon emissions by 80 percent or more by 2050. To do this, we need to stop emitting not just from the electricity sector, but from transportation, agriculture, and manufacturing. Bloomberg and Pope are well aware of this; it’s what most of the book is about. But cities, as a whole, aren’t doing enough right now. To make up for federal inaction under Trump, they have to slam the brakes on emissions immediately.

Many cities and states, for political and financial reasons, won’t do that—not without pressure from the federal government. Indeed, many of Bloomberg and Pope’s great ideas for decarbonization are dependent on Washington. Pope argues, for instance, that we can reduce food waste by investing in better food processing systems in poor countries. The book also accuses the U.S. of propping up coal companies through the tax code and advocates for reforming the subsidies given to fossil fuel producers and agricultural interests. These are all good ideas—and none can happen without the federal government.

The biggest problem with Bloomberg and Pope’s optimism is not that they believe cities and businesses will play an important role in the climate fight. They’re right about that much. They’re also right that cities and state can do more for their citizens, and more quickly, than the feds can. But it’s frankly dangerous to suggest that the U.S. government isn’t essential to solving this global crisis, for several reasons.

The U.S. government is currently run by conservative radicals who consider government itself to be the problem. They oppose regulations wholesale, and some of them, as presidential candidates over the years, have called for shutting down entire agencies; Trump often said he wanted to abolish the EPA. This may have been hyperbolic rhetoric to appeal to the Republican base, but it was so successful that some right-wing voters, for instance, are outraged that Pruitt isn’t entirely dismantling the agency that he’s been charged with running. Trump’s proposed 30 percent cut to the EPA isn’t satisfactory enough, apparently.

This rhetoric demands a response, not silence, from the nation’s political leaders on climate; the spread of anti-government sentiment is no excuse to leave the government out of the climate equation, and doing so risks implicitly conceding the extremists’ position. What’s more, it’s apparent from Climate of Hope that cities and business can’t make up for government inaction. They lack the necessary consensus and coordination—and even if that were to change, their interests are too fickle to count on. Cities are often cash-strapped and frequently change political hands, while corporations are beholden only to their bottom dollar and shareholders.

Bloomberg’s argument may have political and emotional salience under Trump, but it lacks the pragmatism that he claims to espouse. Only the U.S. government can create a long-term, nationwide solution to climate change, and to impel everyone to follow it. Many conservatives condemn this as federal overreach, or even fascism. So be it. We are at war with climate change, and must mobilize accordingly. That is the only truly pragmatic approach to saving the planet.