In all the intensity of feeling aroused by the war, we have somehow let escape us the consideration that the German ideals are the only broad and seizing ones that have lived in the world in our generation. Mad and barbarous as they may seem to minds accustomed to much thinner and nicer fare, one must have withdrawn far within a provincial Anglo-Saxon shell not to feel the thrill of their sheer heroic power. We have heard so much of the German industrialism and militarism that we have overlooked the reservoir bursting with spiritual energy that twentieth-century Germany has become.

The bubbling intellectual and economic energy of present-day Italy is German; Nietzsche has raged through Italian thought, and when it was not Nietzsche it was Hegel. British political thought for forty years has come straight from German sources. What is the new social politics of liberalism but a German collectivism, half-heartedly grafted on a raw stock of individualist “liberty”?

Our own progressivism has been a filter through the British strain, diluted with evangelical Christianity. Our educational framework has been German, though unintelligently so. Architecture and art-forms in England and Scandinavia are strikingly German. Town-planning methods and ideals have been lifted bodily. The French seem to have been driven by repulsion into sadly spiteful degenerations of taste in architecture and art-forms. Scarcely a country has been untouched by the German influence. No other country, except Russia, has been so flooding its influence over the twentieth-century world.

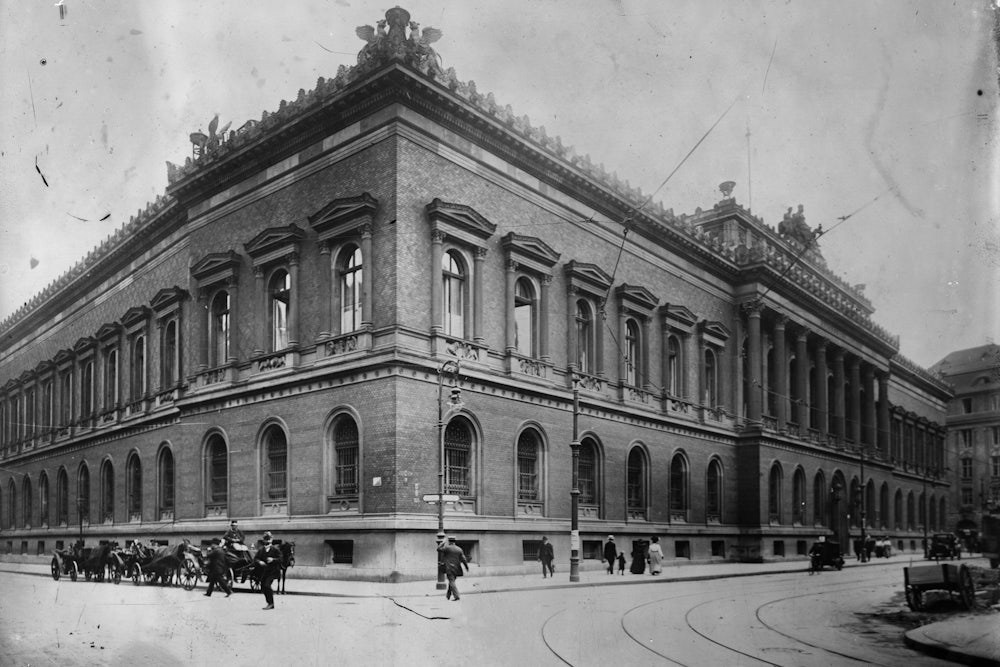

Surely the final test of a vital and fecund civilization, a civilization that has arrived, is the creation of novel and indigenous art-forms, that express with creative fidelity the spirit of the time. And mainly in Germany has there flowered in these first years of the century an original art—that shown in public buildings and domestic architecture of clean, massive and soaring lines, sculpture of militaristic solidity like the Leipzig and Bismarck monuments, endless variety of decorative and graphic art, printing and household design, civic art as embodied in the laying-out of cities and squares and parks. All this development has been of social art. Music and painting, the private cultivations, have been relatively feeble.

Into social, public, reproducible forms has gone this burst of the daring German genius. And everywhere, as in the great ages of creative art, the styles are those in which form grows out of function, so that the work of factories and water-towers and railroad bridges suggests the motives of design. Steel and cement set the lines for wholly novel forms. The world sneers at this art. The world would. But the surge of German art-spirit, with its creation of novel forms, means one thing—that German ideals have a sure spiritual fecundity.

Our American mind has missed the significance of these social forms. We are not used to thinking in terms of the impersonal. The cosmic heroisms of the German ideal fall, too, strangely on our ears. We are not accustomed to gloat over history. It comes to us as a shock to find a people who believe in national spirits which are heroic, and through the German spirit, in a world-spirit; for “the world-spirit,” says one of their professor-warriors, “speaks to-day through Germany.” We have no analogy for the fact that “the ideal of organization, the thought of a tremendously valuable whole, uniting its free members for effective work, labors in the subconsciousness of millions of Germans, labors even where it does not come to the light of philosophic discussion.”

Yet it is scarcely strange that the Germans should expect that a pioneer people like ourselves, of vast and restless energy, should sympathize with a pulsating ideal of organized energy which sinned through excess rather than defect, a true pioneer of twentieth-century civilization, which strove, as a great German has put it, “not for world-dominion, but for a rational organization of the world on the basis of voluntary cooperation, through the welding of a federal union of nations akin in interests and civilization.”

The outstanding fact is that native American opinion did not take the side of the German ideal. When we were challenged we went with hearty unanimity against this ideal, the most fertile and potent before our eyes. Whether because we relapsed atavistically to our British roots, or because the incalculable energies of the German ideal really daunted us, we preferred to range our sympathy with the nations that were living on their funded nineteenth-century spiritual capital, rather than breaking new paths and creating new forms for a new time. Believing the German to be in error, we did not even feel a weakness for the tragic and heroic error as against the safe and fuddling plausibility.

I do not say that we did wrong in repudiating the German ideals, I only want to know what our repudiation means. It seemed intuitive rather than deliberate. It seemed to mean that we sensed in the German ideals tastes and endeavors profoundly alien to our own. And although it becomes more and more evident that, whatever the outcome of the war, all the opposing countries will be forced to adopt German organization, German collectivism, and have indeed shattered already most of the threads of their old easy individualism, we have taken the occasion rather to repudiate that modest collectivism which was raising its head here in the shape of the progressive movement in national politics.

We must not let ourselves forget that such an attitude implies a rejection of the most overwhelming and fecund group of ideas and forms in the modern world, ideas which draw all nations after them in imitation, while the nations pour out their lifeblood to crush the generator. Such a renunciation imposes upon us huge responsibility. We cannot seriously think merely of spewing everything German out of our mouths. To refuse the patient German science, the collectivist art, the valor of the German ideals, would be simply to expatriate ourselves from the modem world. They will not halt for any paltry distaste of ours. By taking sides against Germany we have committed ourselves to the arduous task of setting up ideals more worthy than hers to win the allegiance of our generation and time.

In this severe enterprise we shall get little help from the Allies whose cause we find to be that of “civilization.” Both England and France are fighting to conserve, rather than to create. Our ideal we can only find in our still pioneer, still struggling American spirit. It will not be found in any purported defense of present “democracy,” “civilization,” “humanity.” The horrors of peace in industrial plutocracies will always make such terms very nebulous. It will have to be in terms of values which secure all the vital fruits of the German ideals, without the tragic costs. It must be just as daring, just as modern, just as realistic. It must set the same social ends, the realization of the individual through the beloved community. It must replace a negative ideal of freedom as the mere removal of barriers by a freedom of expansion which consists, to quote the German, “in making the outward social forms adequate to the measure of the fullness of the national spirit.”

Our ideal must be just as creative, just as social as the German, but pragmatically truer and juster. For we find in the German ideal, rousing and heroic as it is, the fatal flaw that has shattered the world’s sympathies. The German “does his best in creating a highly organized community for the purpose of furthering in society the historic development of eternal values.”

Here is the vitiating touch—not in the ideals, but in their direction and animus. For if your enterprise is to be the working out of ideas, your success clearly depends upon living in a world where such ideas can be worked out. If they are set for you and the impulsion is all from behind, you take the truly colossal risk of assuming the perfect congeniality of the universe wit your historic ideas. Let there be the smallest perversity in your world, the smaller kink on your historic path, and your ideals becomes a gigantic engine that has broken loose and lies threshing about in endless havoc. To work out a rigid ideal, the resistance you meet must be of the kind that transfigures both you and the resister. Belgium was not transfigured. If resistance is tough, your march becomes like the ruthless hewing-through of might.

It has been the tragedy of the German spirit that it has bad to dwell in a perverse universe, so that what from within looked always like the most beneficent working-out of a world-idea seemed from without like the very running-amuck of voracious power. German ideals have, in fact, been floated on the stream of a great will, which has been no more a part of their detailed embodiments than the current is a part of the river craft. The German ideals, embodied in German forms, are those of a peace-state. They can be conceived of as existing perfectly and indefinitely without this war. The German has confused the current with the rich and precious freight it was bearing. He often suggests a wistful desire to be tolerant. His ideals are tolerant. But, with his will, he is tragically unable to secure mutual understanding. His idea, with its terrific historic momentum, goes on grinding itself out, heedless of the world-situations in which it finds itself.

Our American contribution will then be not to crush the craft but to change the direction of the current. For the will, to substitute a great desire! Our ideals will not be pushes, but goals. For the expression of eternal values we will have the realizing of social ends through intelligent experimentation. To envisage the good life that we desire for our community and society, and to work towards it with all the intelligence and skill and resources we have—this must be our ideal. Whatever the German has that is life-enhancing—and a nation that lives so habitually at a maximum of energy must have more than we—that we must have, but it must come as the fruit of our intense desire and our intelligence in adapting means to ends, not as an imposed historic value. Our future must be the most intense focusing of our aesthetic and scientific possibilities.

In the pragmatism of Dewey and James and the social philosophy of Royce, we have the intellectual tools for such an enterprise, ethical, social, political. We already see this spirit, barred from politics, making its way in educational and civic movements and in the thought of a younger generation. To set up such an American ideal would be to meet in overflowing measure the responsibility we put ourselves under in rejecting the German. To work out a democratic socialized life by deliberately applying intelligence and taste to the command of human and natural resources would be to set before the world an ideal far more fecund than that with which the Germans have challenged us. It would be beneficent and healing. Its power would really be to unite the world.