What exactly does it mean to be free? “Freedom” was the mantra of the Cold War, at least on the Western side of the Iron Curtain. In the American mind, it is most often associated with the freedoms guaranteed in the Constitution, the country’s secular bible: freedom of the press, of assembly, and so on. But there are other kinds of freedom, too, the material kinds that the United States so vehemently refuses to guarantee: freedom from hunger and poverty, freedom from preventable illness, freedom from homelessness, freedom to rest when you’re sick. The civil rights anthem “I Wish I Knew How It Would Feel to Be Free” is an American song, not a Soviet one. And then there is the constellation of smaller, more intimate freedoms that do not rely on state sanction. The freedom to do or say what you consider right, regardless of the consequences; the freedom to help your neighbor or turn away.

These varieties of liberty are at the core of Free: A Child and a Country at the End of History, a brilliant hybrid of memoir and political theory by Lea Ypi, who was born in Stalinist Albania and is now a professor at the London School of Economics. The title might suggest a familiar story about liberation from the shackles of communism: Cruel dictators are toppled, either in person or in effigy, and formerly downtrodden prisoners of the Eastern bloc queue joyfully for their first taste of McDonald’s. Francis Fukuyama’s phrase “the end of history” was widely employed to describe the new era that supposedly came after the collapse of the state socialist project, when the vagaries and violence of history were to be replaced by an eternity of peaceful economic interdependence. This narrative is still popular in the United States, putative winner of the Cold War, largely enduring the recent descent of many parts of Eastern Europe into illiberalism.

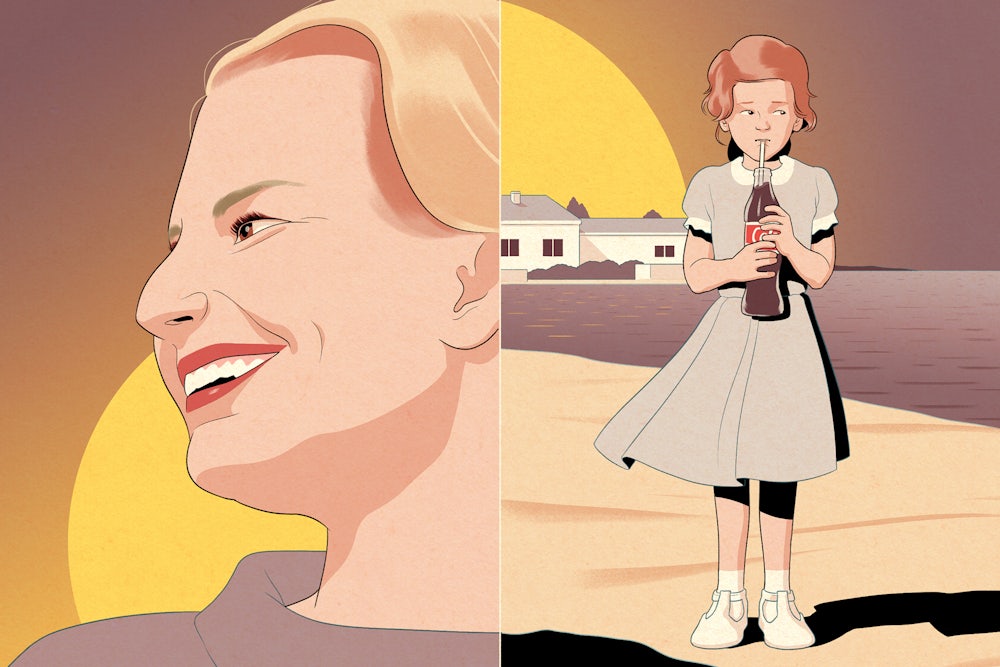

But Ypi’s book is something far more original, a badly needed corrective to the usual script. Where many tales of state socialism are somber, even maudlin, Ypi is witty and acute. Free opens in December 1990, with a comic jolt: Eleven-year-old Lea is hugging a Stalin statue for comfort. Protesters are chanting freedom, democracy, dogs are barking, and the statue has been decapitated. She is frightened and confused. At school, her teacher, Nora, always taught her to love Stalin, the last true communist leader before the Soviet Union gave in to cowardly revisionism. When she makes it back to her house, she finds her parents terrified for her safety. She doesn’t know it, but Albania is in turmoil.

Ruled for 40 years by the revolutionary partisan fighter Enver Hoxha, Albania had long seen itself as a bastion of independence between “the revisionist East” and “the imperialist West.” It had been profoundly isolated since it had broken with Yugoslavia and the Soviet Union over their rejection of Stalinism and with China over its embrace of market reforms. But Albania was not immune to the changes sweeping Eastern Europe. Just a few days before Lea stumbled into the protest, Albania had been declared a multiparty state, with free elections to come. Also on the horizon: economic collapse, a desperate wave of mass emigration, and civil war. Gracefully and irrefutably, Ypi uses her family story to show that even for a society as repressive and immiserated as socialist Albania, the transition was not a happy ending, as the standard narrative teaches. Liberal capitalism brings its own brand of unfreedom.

Lea had already sensed that she was living a double life. She was an avid student, clinging to her teacher Nora’s encomia to socialism and “Uncle Enver,” eager to join in celebrations of communist partisans. But her family didn’t quite fit in. Though she begged them for an example of a heroic relative whose story she could share in school, they could never find anyone convincing in the family tree. Even her family name was a problem: By coincidence, her parents explained, her father had the same first and last names—Xhaferr Ypi—as a quisling prime minister who was a principal villain in her school history lessons.

Lea knew that her parents and her paternal grandmother, Nini, who lived with them, had unfortunate “biographies,” in a country in which biography was destiny. She wasn’t sure why. They were intellectuals—a bad thing—but frustrated ones. Her father, whom everyone called Zafo, loved math and had wanted to become a teacher, but the Party said he had to join “the real working class.” He became a forester. Lea’s mother, Doli, loved literature and music, but she had to study science because her family was so poor; Doli’s father cleaned gutters, and her mother worked in a chemical factory. As a child Doli had often gone hungry, but as a young woman, she was a national chess champion. She told Lea, “The beauty of chess is that it has nothing to do with biography.” Deeply incompatible, Lea’s parents had met and married purely because of “biography.”

Ypi metes out her family’s stories to the reader only gradually, in the same fragmented, sometimes misleading way that she learned them as a child. As it becomes clear that the protests for freedom and democracy are not going away, tongues loosen, and Lea begins to get a clearer picture of her parents and grandmother. Eventually they explain that the protesters want real democracy and real freedom. They never supported the Party and recited its slogans only to avoid punishment. Their family and friends had spent years in prison; many had been executed, died, or committed suicide there. Xhaferr Ypi, Albania’s tenth prime minister, was not a coincidental namesake but Lea’s great-grandfather. His son, Lea’s grandfather and Nini’s husband, had been a dedicated socialist and friend of Hoxha’s, but for his father’s crimes he had served 15 years in prison. The first Xhaferr Ypi was the blight on her father’s biography that had destroyed his dream of becoming a math professor. Lea’s mother, meanwhile, was the daughter of a wealthy family that had once owned land, factories, and real estate. One of their expropriated buildings became the Party’s headquarters. In 1947, Lea’s maternal grandfather jumped out of its window to escape torture, shouting “Allahu Akbar.”

With the advent of a new political system, the rift between Lea’s parents becomes more pronounced. Under socialism, Doli loved to watch Dynasty on Yugoslav TV. Before Lea’s birth, an attack of nerves caused her to lock herself in the bathroom trying to do her hair like Margaret Thatcher’s. Lea had always believed that her mother was not interested in politics, but Doli was only keeping her mouth shut: In fact, she has a Thatcherite belief in self-reliance, competition, and meritocracy. For her, “the world was a place where the natural struggle for survival could be resolved only by regulating private property.” Now she dedicates herself to a quest to get her family’s property back. The rules of nature’s chess game were disrupted by the misguided socialist project, and the pieces must be returned to where they stood before the revolution.

Zafo, by contrast, believes in the inherent good of human nature, the tendency to cooperation. He is an idealist who still idolizes romantic revolutionaries—all of them dead. His great fault, Lea comes to realize, is that he does not have any positive vision of a possible future. After Albania’s liberalization, he gets a job as director of the port. As part of the “structural reforms” advised by the “international community,” he is assigned the job of laying off a large proportion of the port’s workers, many of them poor Roma people who are unlikely to find any other employment. The workers beg him to save their jobs. He never signs off on the redundancies, but he never proposes any alternative either. He despairs at the realization that although the oppression of the old regime is gone, he still isn’t free: He “assumed, like many in his generation, that freedom was lost when other people tell us how to think, what to do, where to go. He soon realized that coercion need not always take such a direct form.” In this case, he simply doesn’t matter: With or without him, the Roma workers will soon be unemployed.

Zafo himself once explained to Lea that, under capitalism, “It’s not that the poor are not allowed to do all the things that the rich can do. It’s that they can’t do them, even if they are allowed. For example, they’re allowed to go on holiday, but they need to keep working because, otherwise, they don’t make any money.” At the beginning of Free, Nora the teacher is an adroitly drawn comic figure, teaching her students to worship Stalin and Hoxha as figures who occupy a space halfway between God and Santa Claus. But there are plenty of kernels of truth in her lectures: “In the dictatorship of the bourgeoisie, a poor black person cannot be free. The police are after him. The law works against him,” or, “People work like dogs, and the capitalist doesn’t even give them what they deserve, because, otherwise, how would he make a profit?” In the festive hubbub of the first day of school in September, Nora remarks, “In imperialist countries we tend to observe this enthusiasm only during the sales period.” If only she could see Black Friday at Walmart. (Her remark is lost on her pupils, who don’t know what a “sale” is.)

When capitalism arrives in Albania, Western-style branding and consumerism prove irresistible. Lea collects gum wrappers discarded by other, more privileged children, often tourists, who have colorful toys in an exotic material and fill the beaches with a powerful, seductive odor that is, she learns, something called “sun cream.” (Albanians content themselves with olive oil.) Doli buys an empty Coca-Cola can that she displays in a place of honor, using it as a vase for a single rose. On a trip to Greece with Nini, Lea sees a plastic bag and plastic cutlery for the first time. “So pretty,” Nini says. “They didn’t make them like this before the war.” Lea makes a list of all the things she experiences for the first time: air conditioning, bananas, the taste of Coca-Cola (from a can and a bottle, though she doesn’t understand why both varieties are needed), traffic lights, jeans, a shop without queues, border control, “queues made of cars instead of humans,” and the Acropolis—but only the outside, because she and her grandmother can’t afford a ticket.

The Westerners who descend on Albania to offer their wisdom have little concern for the wishes of Albanians themselves. Doli begins working with a French feminist NGO. In Albania, as in many post-socialist countries, international NGOs were a lifeline, less because of their intended “capacity building” or forging of a new “civil society” than because they paid decent salaries and provided desperately needed material and social benefits. Doli is motivated not by any interest in feminism, but because she wants to help Albanian women visit their children who have emigrated abroad. Without the imprimatur of an international organization and a planned meeting in some European capital, it would be impossible for these women to receive visas, and they could never afford the trips on their own. “Affirmative action! Feminism!” Doli complains. “What about mothers and their children? ... But no, letting these mothers see their children, that’s not what they mean. It’s about teaching us representation or participation or some other fantasy like that. Of course. That doesn’t cost them anything.”

When the French feminists come to visit in the summer of 1992, Doli thinks carefully about her outfit. Nini suggests a one-piece. At the secondhand store, which stocks Western clothes, Doli selects a red silk dress adorned with black lace and ribbons. She welcomes the French feminists into her home dressed in a negligee: Having never seen such a thing, she couldn’t recognize it as such. The meeting doesn’t go well, though it’s not Doli’s outfit that’s the problem. One of the French women asks, “We know, under socialism, there was much rhetoric about women’s equality. But what was the reality? Did Albanian women experience harassment?” Doli is confused—what is “harassment”?—and replies at last, to the horror of her guests, “Sure. I always carried a knife.” In America, she continues, they have the freedom to carry a gun, but unfortunately Albania is not yet so free. In Ypi’s hilarious retelling, the conversation encapsulates the gulf between the experience of French women, concerned with relatively abstract questions of representation and respect, and Albanians, for whom the primary struggle is a more immediate form of survival.

Lea’s family and their neighbors are taken aback by “the Crocodile,” a Dutch World Bank functionary who gets his nickname from the reptile that mysteriously adorns all his shirts. (The locals speculate that he must really love crocodiles—they’ve never heard of Lacoste, and have not yet learned the concept of logos.) He hops from one country to the next, comparing each to the other, never learning the language, failing to remember the names of local landmarks: For him, globalizing capitalism has made the world flat and small differences irrelevant. When the neighborhood holds a lavish welcome party for him, he gets terrible indigestion and becomes angry when they ask him to dance: He yells that he is free. Soon he’ll leave to supervise “structural reforms” in some other “transitional” or “developing” country—it doesn’t much matter which one. For Nora the teacher, universality was in suffering and the need for proletarian struggle. For the Crocodile, universality is in the unidirectional nature of history toward liberal capitalism.

“Freedom works!” James Baker, U.S. secretary of state, told a crowd of 300,000 Albanians in 1991. This truth was not self-evident. The foreign experts who flocked to post-socialist Albania to give advice failed to prevent more than half of Albanians from losing their savings to blatant pyramid schemes. The scam victims, whose ranks included Lea’s parents, were seduced by promises of Western-size returns on their investments, at a time when the state social safety net was in tatters, old modes of mutual financial aid had disappeared, and new inequalities made people ashamed to ask for loans from neighbors and friends, as they once had.

When the pyramid schemes collapsed, many Albanians accused the government of collusion. There was poverty, looting, violence, and eventually, in 1997, civil war. Some of Lea’s neighbors armed themselves with Kalashnikovs, pistols, barrel bombs, and even medium-range rockets looted from military garrisons. Others—including Lea’s mother and brother, who left impulsively during a trip to the beach—got on boats bound for Italy, where they became refugees, cleaners, laborers, and sex workers, provided they were allowed in. Albanians could finally leave their country, but they were soon barred from all desirable destinations. “The West had spent decades criticizing the East for its closed borders,” Ypi writes, “funding campaigns to demand freedom of movement, condemning the immorality of states committed to restricting the right to exit…. But what value does the right to exit have if there is no right to enter? Were borders and walls reprehensible only when they served to keep people in, as opposed to keeping them out?” The rejection of Albanian refugees was a taste of the more recent “Fortress Europe” tactics that have killed so many. Most recently, refugees from Iraq, Iran, Syria, and Afghanistan froze in the forests of Belarus, refused entry into Poland, Latvia, and Lithuania.

“When freedom finally arrived,” Ypi writes, “it was like a dish served frozen. We chewed little, swallowed fast, and remained hungry.” Albanians were free of the Party, free from prison terms for “agitation and propaganda,” free to worship their chosen god, and free to buy anything they chose and study anything they pleased and wear whatever they liked—but only if they had the money. They were free to leave their country, but not free to arrive somewhere else.

Free is a riveting memoir, written with the skill of a novelist. But it is also a struggle against the political void that followed 1989, the supposed “end of history.” During the 1990s, Ypi writes, there was “no politics, only policy.” From all directions, there was a failure to think honestly and imaginatively about how to help people achieve the greatest possible freedom—political, material, moral—within the complex constraints of real life. Liberal capitalist triumphalism was unfazed by Albanian pyramid schemes, the collapse of the Russian ruble, rampant inequality, or looming environmental catastrophe. Western socialists, meanwhile, were a tiny, nearly powerless faction often distinguished by blind idealism.

Ypi describes her bemusement when she went to university and met socialists who, like her father, chose all their idols from among the murdered: Rosa Luxemburg, Salvador Allende, Che Guevara, Trotsky. When she spoke about her own experiences of socialism, they leaped to correct her—what she had experienced, they explained, was not real socialism. Rather than learning from the failed socialist states, from the trajectories of socialists who had not been murdered but had instead won and kept power, they chose to dismiss these difficult stories. For Ypi, both the capitalist and the Western socialist attitudes are evasions of responsibility, refusal to acknowledge that history is always made, and freedom always exercised, under imperfect conditions.

Today, Ypi identifies as a socialist, to the horror of her Albanian family. She teaches Marx, whose work was a revelation to her once she was able to untether it from Party dogma. But her brand of socialism is clear-eyed, willing to admit failure, disappointment, shortcomings. She is interested in moral freedom rather than utopia. The false lesson often drawn from the collapse of state socialism in the Eastern bloc is that socialism itself can never succeed, that it’s a losing strategy—and capitalism despises a loser. But Ypi draws an entirely different conclusion: “When you see a system change once, you start believing that it can change again.”

This article appeared in the March 2022 print edition with the headline “Free Fall.”