We’re in a period of atonement for the 1990s. In the last few years, TV series and movies have revisited and revised narratives about the lives of Marcia Clark, Tonya Harding, and Anita Hill. A forthcoming series about Lorena Bobbitt will do the same. Charlie Rose and Matt Lauer, who became fixtures of national news in the 90s, have resigned amid allegations of misconduct. In the wake of #MeToo, Monica Lewinsky reflected on the humiliation that the media and powerful figures inflicted upon her decades ago.

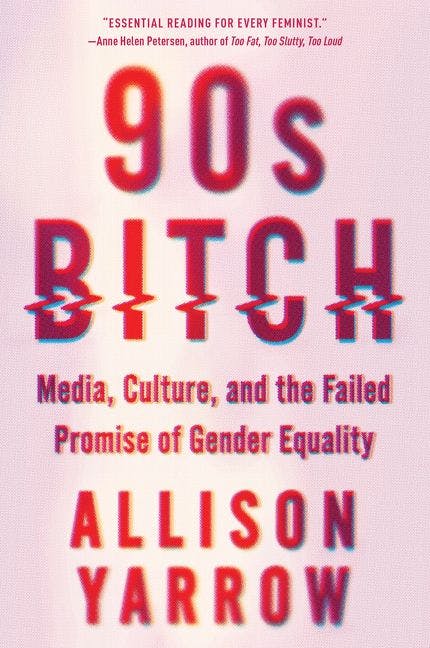

In her trenchant book 90s Bitch: Media, Culture, and the Failed Promise of Gender Equality, Allison Yarrow looks back on that decade with a heightened awareness of sexism and connected forms of discrimination. Yarrow hones in on the 90s because, she says, Americans had assumed that feminist gains of the past several decades would continue. Instead, the 90s brought many disappointments. The press demeaned women who sought influence, and in Victoria’s Secret stores and on the pages of Cosmo, consumerism masqueraded as female empowerment. “The trailblazing women of the 90s were excoriated by a deeply sexist society,” Yarrow writes. “That’s why we remember them as bitches, not victims of sexism.”

90s Bitch is the latest in a string of books that have come out since Trump’s election, all centered on the hostility that defiant women have faced, whether they are mid-century intellectuals (in Michelle Dean’s Sharp), pop culture icons in the 2010s (in Anne Helen Petersen’s Too Fat, Too Slutty, Too Loud), or black women now (in Brittney Cooper’s Eloquent Rage). Like these volumes, 90s Bitch establishes that many of the gender troubles of the last few years—a presidential candidate calling his opponent a “nasty woman,” companies using female “empowerment” as a marketing ploy, a group of men threatening violence against women they believe have unjustly denied them sex—follow in a long tradition.

The 90s, Yarrow argues, was the crucial flashpoint. “Discrediting women based solely on their gender, sexually harassing them, and reducing them to their fuckability endures today from the school yard to the boardroom,” she writes, “in part because this was, writ large, ubiquitous and accepted behavior in the 90s.” The 90s is prologue, and if we want to write a better future, we need an accurate account of this past.

The 90s can claim plenty of triumphs. It’s the decade when the third wave of feminism gained momentum. Congress passed the Violence Against Women Act in 1994. Americans witnessed a succession of political milestones from the appointment of the first female Secretary of State to the first female Attorney General and the first black woman in the Senate. The now often-memed Ruth Bader Ginsburg joined the Supreme Court bench and soon after helped strike down discriminatory laws. Women dominated pop culture, as concertgoers flocked to watch the all-women lineup at the Lilith Fair and audiences filled the Off-Broadway theater that housed The Vagina Monologues, Eve Ensler’s showcase of taboo-shattering stories about women’s relationships with their bodies. Even the fictional world was peopled with powerhouse women: Murphy Brown, Buffy, and Khadijah James in Living Single, to name a few.

While Yarrow acknowledges these marks of progress, she insists that if you take a closer look the decade was scarcely a period of advancement for gender equality. Sexist reactions trailed women who had the nerve to enter prominent positions in the public sphere—whether as politicians, performers, or athletes. After ascending to one of the country’s most powerful roles, Secretary of State Madeleine Albright couldn’t even enjoy the dignity of being referred to by her title. An administration official recalled how people who just met Albright would address her as Madeleine, “something you’d never imagine with a male secretary of state.” The 90210 character Brenda Walsh inspired an ardent anti-fan club that produced “I Hate Brenda” paraphernalia and a vitriolic newsletter about her; Brenda’s reputation as a “bitch” clung even to the actress who played her, Shannen Doherty. At times, the Grammy award-winning musician Paula Cole received less attention for her music than for her unshaven armpits. A woman with visible body hair was apparently such an oddity that it inspired a recurring joke on The Tonight Show. Jay Leno made a Paula Cole doll that had rotating armpits. He used it to shine his shoes.

Appalling events tended to be the prerequisite for progress. After the O.J. Simpson verdict, domestic violence shelters saw a sharp uptick in calls and donations. Anita Hill’s testimony before an all-white male committee and the press’s treatment of her (the pundit David Brock famously described the law professor as “a little bit nutty and a little bit slutty”) motivated more women to run for office than ever before in U.S. history. American women’s outrage culminated in the so-called “Year of the Woman,” when a record number of female candidates were elected in 1992. In the six years after the hearings, the number of sexual harassment claims filed with the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission nearly tripled. These developments, however, resulted from female victims having their credibility scrutinized on national television.

Journalists too often failed to imagine how a woman could be both a victim and a perpetrator—and how being the former could lead to the latter. TLC’s Lisa Lopes set her boyfriend’s house ablaze following a history of domestic abuse. But news organizations ranging from the Atlanta Journal-Constitution to the Chicago Tribune told a simple story with Lopes cast as the villain and her boyfriend, the NFL player Andre Rison, as the victim. Even reporters who did note Rison’s record of abuse used language that downplayed its seriousness. A Rolling Stone feature described the “fateful evening” when Lopes set her boyfriend’s house on fire “after an unusually violent lovers’ quarrel.”

Then there was Lorena Bobbitt, who supplied news, tabloids, and late-night TV with months of infotainment. When Bobbitt faced assault charges for cutting off her husband’s penis, newspapers relayed Bobbitt’s claims that her husband repeatedly raped and physically abused her. But that grim part of the story didn’t move the press to adopt a more solemn tone. Journalists pushed forward the sensational narrative of a nutso man-hater let loose with a 12-inch knife. Yarrow laments: “The media couldn’t separate rape and sex abuse from the comedy and tragedy of a missing penis.”

Even one of the most unapologetically confrontational feminist achievements of the 90s, the Riot Grrrl movement, ends with the dilution of its core message. Most women probably know Riot Grrrl from its derivative forms: the mantra of “girl power” espoused by the Spice Girls, rather than the underground feminist scene that originated the term. Riot Grrrl was sparked at a meeting in Olympia, Washington, where a group of women came together to discuss sexism in the punk scene. The movement’s musicians, writers, and activists developed an alternative vision of girlhood—non-violent, anti-consumerist, and celebratory of girls. In their lyrics, bands like Bikini Kill and Heavens to Betsy addressed issues usually reserved for health class: eating disorders and sexual violence. But as the movement’s reach broadened, the revolutionary nature of its message receded. “Ultimately, it ceased to be a rebellion at all,” she finds, “and instead became a full-on shopping spree.”

Girl power spread images of independent women and supportive female friendship, but it also glorified less venerable ideals. This was the decade that brought Girls Gone Wild to the screen and made Brazilian waxes de rigueur, when girls pined for prohibitively expensive American Girl dolls and Limited Too clothes. Companies were not just selling products; they were selling the idea that being sexually desired by men was a form of power and that buying the right things could build a woman’s self-esteem. Thongs and push-up bras purportedly brought sexual fulfillment and autonomy. Teen magazines pushed clothes and accessories as an avenue toward empowerment. Plenty of women and girls bought it—both the products and the broader message.

In the 90s, media executives contended that they were just giving people what they wanted. They didn’t acknowledge that the content they broadcast could create preferences and norms in the first place. When asked about the pervasiveness of violence against women in TV movies (plotlines that depicted abuse of women defined an entire popular genre of the decade, “Women in Jeopardy”), the president of CBS Entertainment said, “We look to the audience to tell us when they’ve had enough.”

It’s tougher to use that defense now. Audiences are speaking up when they’re incensed by the images of women and girls that they see on their TV or computer screens. Consumers have successfully pressured companies to pull sexist toys, clothes, and ads. A teeming stable of writers is quick to call out misogyny, whether it’s blatant in form or more subtle—and their critiques often appear in the country’s most esteemed publications. In a spirit of rebellion and wit, feminists have drafted new copy for a sexist children’s book and turned a presidential candidate’s demeaning remarks into an elegant deck of (woman) cards. The fierce followings that strong-willed characters like Ilana Wexler in Broad City and Annalise Keating in How to Get Away with Murder have attracted show that there is an appetite for multidimensional female characters who don’t qualify as strictly “likeable.”

The demand for complex plotlines about women extends to the stories about the past, the 90s being front and center. The 2017 film I, Tonya, shows how Tonya Harding suffered from physical and emotional abuse coupled with classism, yet it doesn’t depict her as an unalloyed victim. Forced to revisit the relentless media attention on Marcia Clark’s hair and skirts and supposed bitchiness, viewers of the first season of American Crime Story have recast the once-disparaged prosecutor as a feminist hero. These reappraisals of prominent women of the 90s offer depth and complexity that the original narratives lacked.

But it’s a cancelled revisionist project that might signal the greatest change. A book about the Clinton-Lewinsky scandal was optioned for the fourth season American Crime Story. The project was nixed, reportedly, because the showrunner, Ryan Murphy, didn’t think it was right to dredge up this story without Lewinsky’s buy-in. Murphy said he ran into Lewinsky at an event and told her, “If you want to produce it with me, I would love that; but you should be the producer and you should make all the goddamn money.” While the former president’s thinking may not have evolved much in the intervening decades, Murphy’s decision is a small indication that we’re learning something from the 90s: that women who for decades were known merely as bimbos or bitches, objects of ridicule and shaming, deserve to be the subjects and the authors of their own stories.