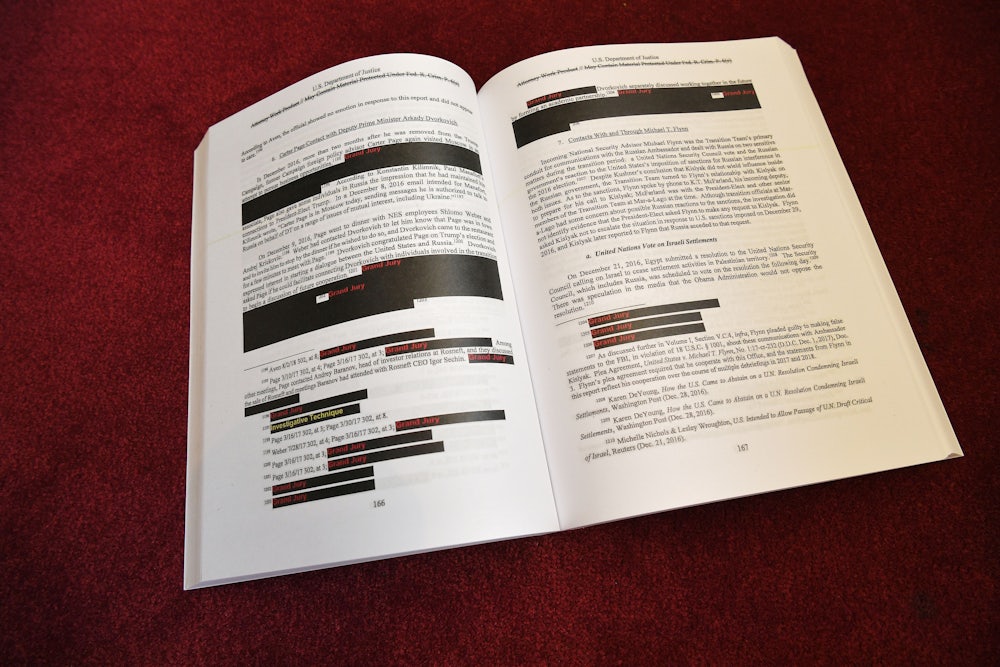

It took less than a week for publishers to get the redacted version of the “Report On The Investigation Into Russian Interference In The 2016 Presidential Election”—more commonly known as “the Mueller report”—into old-fashioned, analog, hold-in-you-hand book form. Scribner, working with The Washington Post, won the race to be the first on physical shelves; their version, fleshed out with an introduction and commentary from Post journalists Rosalind S. Helderman and Matt Zapotsky, is already in bookstores across the country.

Editions from independent publishers Skyhorse and Melville House, the former including an introduction from Trump defender Alan Dershowitz and the latter a “people’s edition,” in the publisher’s words, with no extraneous material, will be released this week; several publishers had put out electronic editions within 24 hours of the redacted report’s April 18 release by the Department of Justice. (Full disclosure: I worked at Melville House for two and a half years and was part of the team that rushed the Senate Intelligence Committee report on CIA torture to print.)

It’s no surprise that these publishers spent sleepless nights pushing the report to print—a very complicated experience, given its numerous redactions and other typesetting oddities. Shortly after the report was released, these three editions held the top-three places on Amazon’s sales rankings; all three stayed in the top ten for the next week, with Scribner’s edition holding its own against Michelle Obama’s historic bestseller Becoming. These three editions are also continuing to do well against an increasingly crowded field of cobbled-together self-published editions—including one by special counsel target and nonsensical plot point Carter Page. Audible, the Amazon-owned audiobook juggernaut, raced to record a 19-hour audiobook of the report, which was released for free (possibly because no one could possibly want to listen to a 19-hour, redaction-laden government document) last Monday. Demand was so high for bound editions of the report that some independent bookstores began printing and selling their own copies hours after its release.

That several publishers were racing to publish—and sell, at a price between $7.99 and $14.99—a report that is publicly available for free says a great deal about book publishing in the Trump era. Yes, the trends were already there, but the current president has accelerated things. For publishers in 2019, in an industry increasingly dominated by quick and easy cash grabs, Donald Trump is where the money is.

Initially, book publishers, like the rest of the media, were slow to take Trump seriously. Given the typically long lead times for writing and publishing books—several months, if not years—many assumed that he would be yesterday’s news by the time their biographies and exposés were released. In 2016, David Cay Johnston’s The Making of Donald Trump—published by Melville House after the big houses shrugged it off—and the Post’s Trump Revealed (published by Scribner) were bestsellers, but sales of both paled in comparison to books that approached Trump’s support more tangentially. J. D. Vance’s enormously flawed Hillbilly Elegy was the year’s breakout hit, thanks in large part to being embraced by the establishment class as an explainer for Trump’s diehard base.

When, however, it became clear that Donald Trump was going nowhere, publishers began pumping out a flood of books recounting his innumerable misdeeds. Michael Wolff’s Fire and Fury (5 million copies sold) and Bob Woodward’s Fear (1.1 million copies sold in its first week) were breakout hits, both detailing a seemingly unending succession of presidential temper tantrums—and the efforts of aides to prevent Trump from blowing up his presidency or, maybe, the world. (For comparison’s sake, Omarosa’s Unhinged sold a respectable 86,000 copies as of late-December.) They are joined by a wave of other books from people with central roles in the drama (Corey Lewandowski’s Let Trump Be Trump, James Comey’s A Higher Loyalty, which has sold over a million copies, Sean Spicer’s The Briefing, which sold significantly less than that), books about people in Trump’s orbit (Joshua Green’s Devil’s Bargain, about Steve Bannon, Vicky Ward’s just-released Kushner Inc.), and a barrage of books just trying to figure out what the hell is happening. Books explaining—and, more often than not, recommending—impeachment have become a micro-genre in recent months, as have books suggesting that the president is a Russian agent (what happens to this genre post-Mueller report is anyone’s guess). And conservative publishing, a juggernaut long before Trump’s presidency, has published a number of bestsellers defending the president and attacking his critics.

The publication of the Mueller report will be followed by a continuous flood of books about Trump and his administration. Post reporters Philip Rucker and Carol Leonnig are working on a book about the administration. So are, in no particular order, MSNBC’s Chuck Todd and Politico’s Michael Kruse; Politico’s Tim Alberta; Esquire’s Ryan Lizza and New York’s Olivia Nuzzi; The New York Times’ Michael Schmidt; the Times’ James Poniewozik; the Times’ Jeremy Peters; the Times’ Julie Hirschfeld Davis and Michael D. Shear; the Times’ James Stewart; CNN’s Jim Acosta; The Daily Beast’s Asawin Suebsaeng and Lachlan Markay; and former UN ambassador Nikki Haley. Trump, unsurprisingly, also wants to get in the game. Last month, the Beast reported that the president was already planning a tell-all memoir aimed at “settling scores.”

The vast majority of these Trump books break little new ground. Many dutifully recreate daily dramas that have already been recorded in the pages of the Times, the Post, and Politico, with a few new quotes and a handful (if that) of new scenes. These items can have important long-term implications—think Fear’s portrait of Gary Cohn taking an executive order off of the president’s desk before he could sign it—but the overall portrait is familiar. We know that Trump is lazy, that he has little practical command over the functions of government, and that he chooses to flout the law at seemingly every opportunity. Above all, he is temperamental, given to tantrums and sulks that play out in private until, that is, they appear in the newspaper—or Twitter.

The Mueller report is, in some cases, the apex of this trend. Though praised by the Post’s Carlos Lozada as “that rare Washington tell-all that surpasses its pre-publication hype” and “the best book by far on the workings of the Trump presidency”—a blurb being used in the Post’s edition—it also encompasses the Trump books that have come before it. As with those tomes, we know all of the juicy parts days, if not weeks, before publication. In the cases of books like Fear and Fire and Fury, they appear as excerpts, ginning up pre-publication buzz. By the time you read the book, you’ve already likely read the best bits; the rest is just connective tissue, filler.

On one level, publishers are doing what everyone else in the news media has done for the past two years. Trump’s ability to sow constant chaos and shift attention toward himself is unparalleled. With so much attention being focused on the Trump administration, publishers have little choice but to follow his lead. But the shift toward Trump—and, in many cases, away from other subjects—is also the result of a number of factors.

Trump books are indeed published because that’s what people are buying, but there are other factors at play. There has been growing pressure on publishers to churn out bestsellers since Barnes & Noble’s emergence as an independent bookstore slayer in the 1980s. While Amazon likes to sell itself as a flat marketplace—the everything store, where you can buy any book (and anything) you could possibly want—it has also been putting significant pressure on publishers to focus on mega bestsellers in recent years. The corporate “Big 5” publishers that dominate the industry, moreover, need those bestsellers because, as publishing industry veteran Mike Shatzkin told me in 2015, they “have big overheads: they have warehouses, they have large staffs. They need volume to move through the system.”

At the same time, it’s never been harder for books to become bestsellers. Over the last few years, publishers have deservedly griped over how hard it has become for books, particularly by unknown or relatively unknown authors to gain exposure. In the post–Daily Show, post–Oprah Winfrey recommending a book nearly every month environment, there is no one television show that can guarantee a huge bump in sales. Reviews in newspapers and magazines have been declining for years. Despite an independent bookstore resurgence, there has still been a decline in physical bookstores, minimizing people’s opportunity to discover books by browsing. The safest way forward is to publish known quantities by authors with an existing fanbase.

Fiction, in particular, has suffered in this environment, with sales down nearly 20 percent since 2013. Without Oprah (and, to a lesser extent, Jon Stewart), and with publishers increasingly unlikely to make the expensive multi-book investments often needed to turn young authors into household names, the big houses are looking more and more to books that can easily generate media interest. No one, of course, generates more media interest than Trump.

The result, however, is an industry addicted to the quick Trump fix—and an industry that is rapidly moving away from one of its seminal strengths. The point of nonfiction books is to offer something that you can’t get on television—or the internet. The long lead times and production work that go into book publishing are meant to allow for added value and perspective. What we’re getting now, however, more often than not, are books that are essentially pricier, glossier versions of stuff we already get day in and day out, in an endless stream, on cable news and on social media. The publication of the Mueller report is, to some extent, the apex of this trend: an officially free report, repackaged and sold for $15. This is not much different than the majority of the Trump content being sold for twice that amount.

This is not to say that Trump hasn’t been a welcome all-you-can-eat sundae bar for cash-strapped publishers in a time when they need a sugar daddy. It’s just a pity that the money they’ll bring in will only pay for more books about Donald Trump.