The World’s Only Corn Palace was crowded on this post–Independence Day weekend when I visited to see it thank me for my service. An estimated half-million tourists a year trek to Mitchell, South Dakota, to admire the odd, onion-domed sports and concert venue, which is decorated in byzantine “crop art” mosaics: Each year, the building’s husk is covered in a new, themed series of murals made entirely out of 13 different shades of dried corn, native grasses, and grains, visual facets of daily life on the plains. In 2005, the year I joined the Army, the theme was “Life on the Farm.” One theme—“Salute to the Rodeo”—was extended for the entirety of my 16-month deployment to Afghanistan, due to a severe drought. This year’s theme, announced on a sprawling corn marquee beside a two-story-tall corn rendering of the Marines raising the American flag on Iwo Jima, was “Salute to the Military.”

Posing for a photo with my fiancée in front of a statue of a smiling giant ear of corn with sleepy eyes, my thoughts wandered to George McGovern, native son of Mitchell. “I’m fed up to the ears,” he’d once said, “with old men dreaming up wars for young men to die in.”

My own war was 18 years old now, its veterans honored on the walls of the edifice behind me, where McGovern’s old high school still played its basketball games. How are people still falling for this stuff?

I realized a partial answer to that question afterward, as we pulled onto Highway 90 and my fiancée set the cruise control at 83 miles an hour. I settled into our car’s passenger seat and thumbed through the Corn Palace snapshots we had snapped. There it was, printed across the front of the T-shirt I’d worn: This was the logical outcome of the Cold Slither World Tour of 1985.

You don’t know about Cold Slither? You clearly weren’t watching Saturday morning cartoons on December 2, 1985, when this seminal episode of G.I. Joe: A Real American Hero aired. The plot was simple: Cobra, the ruthless terrorist organization headed by a multilevel marketer named Cobra Commander, is in dire financial straits following a G.I. Joe raid on the secret vault that hid Cobra’s well-capitalized assets: artwork and stolen gold. The baddies consequently turn to another industry that rewards greedy sociopaths: entertainment. Enlisting the aid of a paramilitary biker gang known as the Dreadnoks, Cobra Commander creates a punk-metal front band, Cold Slither.

Cold Slither’s goals are to generate enough cash flow to keep Cobra’s terrorist plots and plotters alive, while corrupting the minds of America’s youth with lyrical messages of rebellion against the social order:

We’re tired of words

We’ve heard it before

We’re not gonna play the game no more

Don’t tell us what’s right

Don’t tell us what’s wrong

Too late to resist

Cause Cobra is strong

A few Joes briefly come under the spell of Cold Slither, and Cobra Commander hatches a plan to hold an entire concert venue hostage. But ultimately, the unconverted Joes intervene, good ultimately triumphs over evil, and the cartoon’s triumphant theme song once again rolls over the credits.

G.I. Joe: A Real American Hero is a cultural Rosetta Stone, a way to understand and interpret the modern American tendencies to genuflect when confronted with shimmering uniforms and invoke empty phrases like thank you for your service. “After watching G.I. Joe, I asked my mom if I could move to Alaska to fight the communists when I was older,” Adrian Bonenberger, a former infantry officer and fellow combat veteran (as well as TNR contributor), told me when I asked him if he liked the cartoon as a kid. “I identified much more with Cobra, which is probably why I had such an easy time fitting into the U.S. Army.”

It started as a way to sell toys. Hasbro, creators of the original Barbie-sized G.I. Joe toys from the ’60s, wanted to catch some of Kenner’s early-’80s Star Wars action-figure thunder, and so it relaunched a smaller-size military toy line with a fuller back story, initially provided by Marvel Comics writer, Vietnam veteran and self-identified “moderate Democrat” Larry Hama.

In Hama’s hands, the G.I. Joe comic universe subtly deflated America’s military pretensions, putting the individual soldier before any national zeitgeist. He even patterned Cobra Commander, a megalomaniac in thrall to his own tirades, after William F. Buckley. Comics, to Hama, should play as “grand opera” rather than daytime TV. “I received hundreds of letters from soldiers who read the G.I. Joe comics when they were kids and not a single one ever said I sold them a bill of goods,” Hama has said.

The TV cartoon series, launched in 1983 shortly after the comics, was a different creature. Hasbro came to Marvel hoping that a syndicated Saturday show could sell the toy line better than commercials could. “They’d give us lists of characters and vehicles they’d like in a particular episode and then we’d have to figure out how to work them all in,” show consultant Buzz Dixon has said.

No one ever died in G.I. Joe cartoons—the comics were a different story—and problems were solved by a diverse group of highly trained soldiers from all backgrounds who wore no particular standard uniform. The shows were stuffed with martial idealism and ended with public-service announcements by beloved characters, inculcating a weird sort of militarized civic-mindedness with the tagline: “Knowing is half the battle.”

Over the nearly four decades since the Joes’ adventures first titillated TV-watching kids, we began to notice that war-soaked Saturday morning cartoon phrases like “he fights for freedom wherever there’s trouble” were standard fare on Sunday morning political talk shows, too.

Ever since I got back from Afghanistan, I’ve been trying to unpack the long stretch I spent as an infantryman there. “Providing security along a porous border for the people to gain confidence in the democratically elected government of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan” sounded a lot better more than a decade ago, when I didn’t understand what that was code for: propping up certain heroin traffickers as proxies to control and exploit geopolitically significant real estate.

I was naïve. I’d missed the early warning signs about modern American war as a kid—some planted there by the show, but more coming from the biographical file cards that accompanied each G.I. Joe figure, with occasional subversive counterparts to the steadfast militarism of the Reagan era. Those cards had been written by Hama, the veteran, whose family had been held in internment camps for Japanese-Americans during World War II, and whose ethos was “I am against war, but for the soldier.”

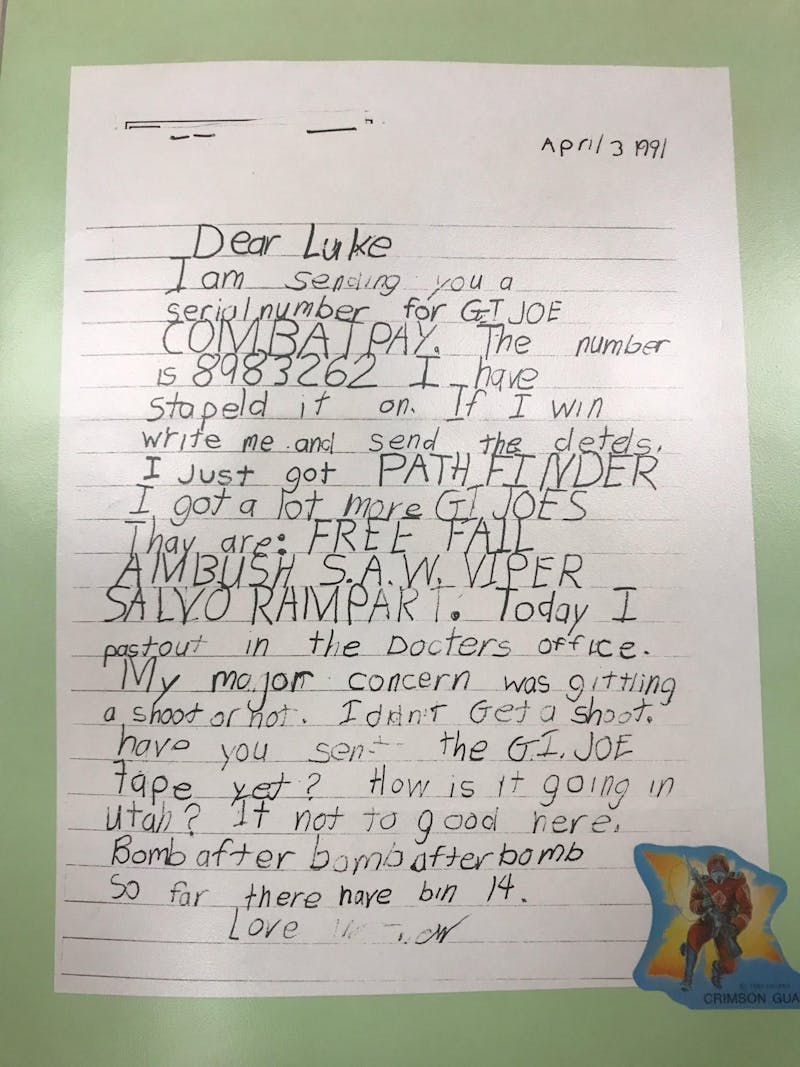

Last week, I was paging through scrapbooks that my mother meticulously prepared and kept for me and my siblings when I came across a letter I wrote to my friend Luke after the Gulf War, when I was seven. We were living in Turkey at the time because my father was in the Air Force.

Dear Luke

I am sending you a serial number for GI JOE combat pay. The number is 8983262 I have stapeld it on. If I win write me and send me the detels. I just got PATHFINDER I got a lot more GIJOES. They are: FREE FALL AMBUSH S.A.W. VIPER SALVO RAMPART. Today I past out in the doctors office. My major concern was getting a shoot or not. I didn’t get a shoot. Have you sent the GI JOE tape yet? How is it going in Utah? It not to good here. Bomb after bomb after bomb. So far there have bin 14.

Love Matthew.

(Luke ended up joining the Navy.)

After rereading the letter, I had to find the file cards of the action figures I’d mentioned, hopeful that perhaps they could help me process why, 28 years later, I found myself at the Corn Palace, growing troubled over the way we put soldiers on a pedestal over teachers and doctors and the folks who work in brutal conditions so I can have strawberries at Walmart 365 days a year.

The cardboard dossier that stuck with me most was the one for Ambush, an expert in concealment from California whose “real” name was Aaron McMahon. Ambush, according to his file card, had “no trouble staying out of sight”:

When he was ten years old, Ambush participated in a neighborhood game of hide-and-seek, then disappeared for three days. It wasn’t until the National Guard was called to aid in the search that his well camouflaged hiding place was discovered under his parent’s front porch.

Concealment is a reflexive talent in a lot of veterans. We conceal our positions in the field. We also grow adept at concealing our misgivings, anxieties, personal problems, and vices. But we can grow acutely aware of what the society we served conceals, too.

A majority of polled American veterans now believes the wars in Iraq, Afghanistan, and Syria weren’t worth the costs they’ve exacted on our country. I’m not sure what share of veterans were as devoted to G.I. Joe as I was, but it’s probably significant. And it’s probably time for us to come out from our concealed places and stop hiding from what these wars say about us. When confronted with those who use the word patriotism as a weapon rather than a balm, we should speak up more and say what we know about the childish way of thinking that wars are what Makes America Great. Real war isn’t as bloodless or as morally instructive as G.I. Joe cartoons. Now we know. And knowing is half the battle.