In 1925 in Berlin, Vladimir Nabokov participated in a literary evening for Russian émigrés living in the German capital; the topic of his talk was a recent boxing match he attended at the Berlin Sports Palace. Of the match, in which the German Hans Breitensträter sparred against Basque boxer Paolino Uzcudun, Nabokov narrated the various blows, knockouts, and bodily excretions that colored the event: “Breitensträter attacked first, and the moan turned into a rumble of delight. But Paolino, hunching his head into his shoulders, answered him with short uppercuts, and from almost the first minute the German’s face glistened with blood.” Nabokov, who made ends meet by giving boxing lessons, assured his genteel audience there was nothing frightful in the violent punches: “I hasten to add that in such a blow, which brings on an instantaneous blackout there is nothing terrible. On the contrary. I have experienced it myself, and can attest that such a sleep is rather pleasant.”

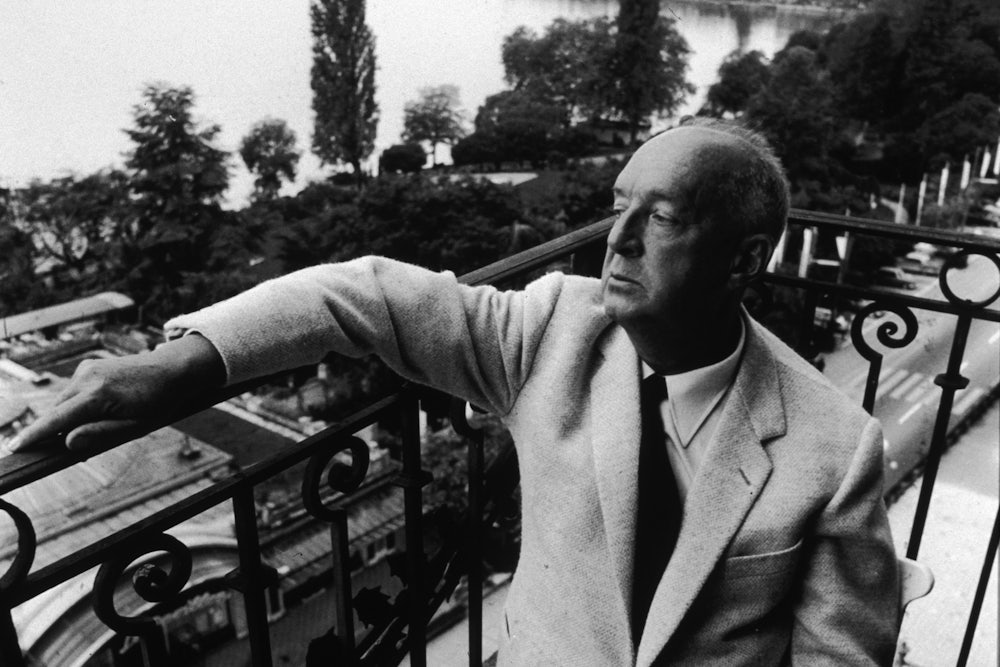

Nabokov spent much of his writerly life sparring. He fought with readers (aggressively dividing them into the categories “good” and “bad” in his university lectures), interviewers (he refused to sit if questions were not sent to him in advance), and—of course—literary critics. The only point of criticism, he said, was that “it gives readers, including the author of the book, some information about the critic’s intelligence.” Though often pictured as a detached, professorial aesthete, cloistered away in a Swiss hotel, Nabokov was, in fact, deeply confrontational. He wrote countless letters to the editor demanding corrections (even for college newspapers) and was famously unkind in his estimation of fellow writers: Of Portnoy’s Complaint, he said, “It is a ridiculous book. It has no literary worth whatever. It is so obvious and not at all funny—a ridiculous book.” He was a frighteningly ungenerous book critic; in one of his more charitable reviews, of an anthology of Russian literature (for The New Republic), he offered this in the way of praise: “This seems to be the first Russian anthology ever published that does not affect one with the feeling of intense irritation.”

Nabokov’s combative voice can be found throughout Think, Write, Speak, a new edited collection of his “public prose.” Brought together by Nabokov biographer Brian Boyd and translator Anastasia Tolstoy, Think, Write, Speak offers an eclectic mix of Nabokov’s nonfiction, from obituaries he wrote to an interview with Sports Illustrated “about the element of sport in butterfly hunting,” to the boxing essay noted above (originally titled “Play”). Think, Write, Speak is essentially a follow-up to the volume Strong Opinions, Nabokov’s first and landmark collection of nonfiction, published in 1973. A compendium of essays and interviews on topics as wide-ranging as Freud, Soviet literature, and segregation in the United States, Strong Opinions was nonetheless, Boyd tells us, something of a “rushed compromise.” Nabokov was desperate to quickly fulfill the 11-book deal he made with his new publisher, McGraw-Hill, and so the volume was filled with mostly topical pieces, including a bevy of interviews he gave after publishing Lolita.

Strong Opinions drew from the post-Lolita era of Nabokov’s career, when commercial success allowed him to devote himself entirely to writing. Conversely, Think, Write, Speak gives us a window into the earlier decades of Nabokov’s life, many of which he spent teaching Russian culture to American audiences to make ends meet, both as a book critic and as a university lecturer. This new collection is an expansive record of Nabokov’s worldview and aesthetic philosophy, but one particularly fascinating element of Think, Write, Speak is the insight it gives us into how Nabokov, staunchly opposed to the politicization of literature, navigated being a public explainer of Russian arts and letters in the midst of the Cold War.

After graduating from Cambridge University in 1921, Nabokov joined his family in Berlin, where they had settled among the city’s large Russian émigré community (the Nabokovs fled Russia after the revolution). Nabokov and his father both published actively in the city’s émigré journals; in fact, Nabokov’s early pseudonym, Vladimir Sirin, was selected so that readers would not confuse him and his father, who often wrote for the same publications. Some of these early works are here in Think, Write, Speak: mainly reviews of new Russian poets, but also obituaries, including one for a friend who was hit by a tram on his way home from a party at the Nabokovs’ in Berlin. There is even a very early essay Nabokov wrote as a student at Cambridge; of life as a Russian among the English, he remarked to his compatriots: “Sometimes I sit in a corner and look out on all of these smooth, no doubt very pleasant faces, but somehow always reminding me of a shaving soap advertisement.” Nabokov and his wife, Vera, left Berlin in 1937 because of growing anti-Semitism (Vera was Jewish) for Paris, where Nabokov continued to be identified as an émigré author, a label that bothered him. In the 1940 essay “Definitions,” included in Think, Speak, Act, he says the term “émigré writer” amounts to tautology: “Any true author emigrates into his art and exists within it. The love of a Russian writer for his homeland has always been nostalgic, even if he never left it.”

Recalling his Russian homeland would become the dominant way that Nabokov supported himself and his family over the next decade. Desperate to escape the rise of Nazi Germany in Europe, Nabokov leaped at the chance to take on a summer teaching post at Stanford University; though just a short-term gig, it was enough to secure visas for him, his wife, and son. In 1940, Nabokov arrived in the U.S., and he eventually found steady work teaching Russian language and literature at Wellesley College, where he would go on to spend the better part of the decade. (While in the Boston area, he also worked as curator of lepidoptera at Harvard’s Museum of Comparative Zoology.) In 1948, he published an essay in Wellesley Magazine on “The Place of Russian Studies in the Curriculum.” Here, Nabokov reflects on the challenges of teaching Russian to American pupils at the height of the Cold War. “Present interest in things Russian,” he complained, “is fairly remote from the direct desire to probe the artificial subtleties of Dead Souls and Anna Karenina.” Students, he said, were “driven to buy Russian grammars” by what he sarcastically called “the pathetic vision of a ‘better understanding between nations.’”

Though he claimed to hold no prejudice against the practical use of languages, Nabokov was clearly frustrated by the logic of area studies, a Cold War discipline, and its encroachment into the world of arts and letters. Students should take Russian “for the spirit of verbal adventure,” he believed, so the transformation of his country’s literary tradition into mere fodder for intelligence-gathering was an obvious thorn in his side. That perhaps explains an exasperated letter to the editor of the Cornell Daily Sun (Nabokov taught at Cornell from 1948 to 1959—among his students was future Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg). Nabokov was irritated that he had been listed as faculty in the department of linguistics, not literature: “I am strictly a Goldwin Smith man,” he wrote, referring to the university’s building for courses in literature.

As a critic, Nabokov likewise

fought against the tendency to view Russian literature through the prism of

politics, though in this case, he was battling against the leftist sympathies

of many critics, and his own friend and editor Edmund Wilson. Nabokov’s introduction

to the American literary scene was shepherded by Wilson, who solicited

Nabokov’s writing for The New Republic in the early 1940s. For Wilson,

Nabokov reviewed several books with Russian themes (one was a biography of the

Ballets Russes impresario Sergei Diaghilev). Though Wilson and Nabokov would

later have a falling out over an unrelated issue (Wilson’s dislike of Nabokov’s

translation of Eugene Onegin), in several interviews collected in Think,

Write, Speak, Nabokov bemoans what he sees as the critic’s inability to assess

objectively the merits of Soviet fiction. For instance, Boris Pasternak’s Doctor

Zhivago, which Nabokov called “A mediocre melodrama with Trotskyist

tendencies,” had been praised by Wilson. In an interview with The New York

Herald Tribune in 1962, Nabokov complained, “People like Edmund Wilson and

Isaiah Berlin, they have to love Zhivago to prove that good writing can come

out of Soviet Russia. They ignore that it is really a bad book.”

Nabokov was once asked how writing Lolita had changed his life. “I gave up teaching—that’s about all in the way of change,” he replied. He gave up lecturing, yes, but more specifically—he gave up lecturing Americans on Russian literature. As the interviews in Think, Write, Speak show, after the success of Lolita, Nabokov was asked less about his homeland and more about his adopted country, as critics continued to read the novel as an indictment of American morality. In this way, Nabokov wrote himself out of the same Russian literary tradition he had seen abused during the Cold War, when students read novels looking for clues to the rise of Stalinism.

That is not to say Nabokov ever cast off or distanced himself from his Russian literary heritage. In 1958, a Voice of America journalist asked him if she would be interviewing “the Russian writer Vladimir Sirin or the famous American author Vladimir Nabokov.” Nabokov, never too fancy for sports metaphors, assured her: “Don’t be disconcerted by the presence of this ‘combined team.’”