Nothing twitches the loins of a Beltway take-monger quite like those three little words: Dems in Disarray. Pundits have no better reason to get out of bed and race to their sun-dappled desks than to type with trembling fingers that the Democrats are at each other’s throats again. When will they learn that the majority of this country are just simple, Applebee’s salad bar–enjoying Americans who want low deficits and a president who Gets Things Done, not leftist squabbles on Twitter?

This cursed mind-set has not been successfully quarantined in Punditville; it is a virus that infects even smart, well-intentioned Democrats. The idea that Democrats should avoid at all costs fighting in public, and that any sort of significant disagreement over the direction of the party is tantamount to handing the election to the Republicans, is an idea that conveniently serves the agenda of the centrist establishment who have been doing rather well (financially and politically) during the Trump era. It’s an easy fear to stoke. Consequently, even those who don’t actively seek to serve this agenda have internalized this organizing idea. One can see it in the solemn laments for dropped-out candidates like Julián Castro and Cory Booker from people who never intended to support them in the first place. Support a specific candidate if you must, but not too vociferously; if you can’t endorse the idea that the field is one big united team of good folks, havin’ a great time out there, you’re being counterproductive.

Last week, Politico reported that Elizabeth Warren’s closing argument would be a conventional “electability” pitch, focused on the tenuous notion that she is “best positioned to unite and excite the party—and is therefore the most electable.” Among the evidence for this pitch is that she is often listed as the second choice for the three other top candidates. (Second Choice Liz is not necessarily as dazzling an argument as it may initially seem.) If Warren saw this as a way to innocuously smarm her way to the top—Let’s not fight amongst ourselves, I’m just focused on making sure we win—it was undermined immediately by her campaign surrogate, Julián Castro, who said at a rally on January 12 that “a quarter” of voters say they’d be unhappy with Bernie (or Biden) as the nominee.

A minor critique, you may think. But in the same Politico article in which Warren’s pivot to unity was announced, a campaign surrogate shows up, making Castro’s argument in more explicit, aggressive terms:

“Biden won’t be able to get Bernie voters given his position on ‘Medicare for All’ and coziness with banks and credit card companies. Bernie will have a hard time getting Biden voters because he’s made zero effort to repair the rifts of 2016,” said Democratic strategist Adam Jentleson, who is close with Warren’s campaign. “There’s no candidate better positioned to unify and energize Democrats than Warren.”

It should be stressed that we are talking about exceedingly small differences here; an Economist-YouGov poll cited by Politico finds that only 11 percent of voters say they would be disappointed by a Warren candidacy, and 16 percent say they would be disappointed by Sanders. This five-point separation is not particularly impressive. The poll’s margin of error was approximately plus-or-minus 3 percent.

But any pretense of sincerity from Warren’s campaign on the unity front has been completely eroded by the events of the last few days. On January 12, a call script from the Sanders campaign, distributed to some volunteers in at least two states, was leaked to the press. In addition to criticisms of Joe Biden and Pete Buttigieg, the script contained a short segment on Warren to address voters who said they were thinking of voting for her:

“I like Elizabeth Warren. [optional] In fact, she’s my second choice! But here’s my concern about her. The people who support her are highly-educated, more affluent people who are going to show up and vote Democratic no matter what. She’s bringing no new bases into the Democratic Party. We need to turn out disaffected working-class voters if we’re going to defeat Trump.”

It is hard to imagine a more restrained criticism of Warren’s campaign that would still count as a reason to vote for Sanders over Warren, short of the script literally telling canvassers to say, “Oh, that’s fine! Sorry for asking!” The Warren camp nevertheless considered it an unacceptable breach of the so-called “nonaggression pact” for the Sanders campaign to even suggest that Warren’s Lululemon-fresh base might not be enough to win an election. In response to the leak, Warren said she was “disappointed” that “Bernie is sending his volunteers out to trash me,” which is not an accurate description of what his volunteers were doing. Later, the campaign blasted out a fundraising email attacking the Sanders campaign as “dismissing the potency of our grassroots movement.” If there is one thing that is beyond the pale in a Democratic primary, it is suggesting that wealthy, well-educated people might be part of the problem.

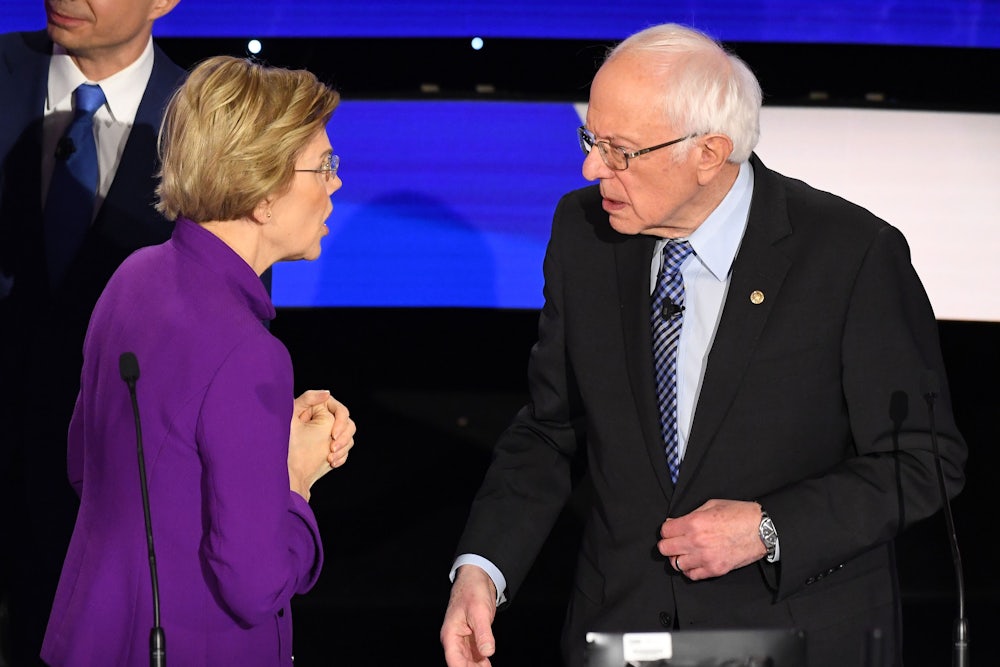

It is impossible to definitively say that what happened next was directly related to the script kerfuffle, but you would have to have the pitiable brain of a particularly pliant kitten to think it wasn’t. On Monday, CNN—followed by BuzzFeed and The New York Times—cited anonymous sources close to Warren claiming that in a private 2018 meeting about the presidential election, Sanders had told Warren that a woman could not win the election. Sanders denied it vociferously and on the record; Warren initially declined to comment and then came out, hours later, with a carefully worded statement. On the debate stage Tuesday, the same dynamic played out, with CNN cheerfully carrying water for Warren’s interpretation of events. (Less noticed was a story in the Daily Beast that alleged a Sanders volunteer had described Warren as not being in favor of Medicare for All. This is another case of very curious timing.)

Warren’s unity pitch would be thin even if all this melodrama had not transpired. She has always been at her worst when she resorts to the tactics of a conventional politician. The “accidental senator” who was drawn into politics by the sheer force of her hatred for Wall Street is far more appealing than the careful candidate trying to be all things to all people. Her double-backtrack dance in pursuit of a “pay-for” for Medicare for All, her blundering attempts to clarify her claims of Native American ancestry—these are the sorts of things that politicians leashed to stolid, tired, Beltway political consultants do. So, too, was her zany effort to establish an online “Fact Squad” to disprove “myths” about her. Launched in early 2019, the resulting site had big Correct the Record energy: The headlines promised to bust bizarre myths such as, “No, Elizabeth Does Not Have a Racist Artifact in Her Kitchen” and “No, Elizabeth Does Not Take Risperdal.” Warren’s tendency to get incredibly cautious and retreat into defensive crouch is reminiscent of how Clintonworld interacted with the media and her critics. There’s a clear through line: Her campaign is conflict-averse and does not handle criticism well.

One of the biggest ironies about the contretemps that unfolded over the past weekend is that it wasn’t one of Trump’s “Pocahontas” slurs, or pundit skepticism about whether she’d tax the middle class to pay for single payer, or whatever that whole Risperdal thing was, or even some explicitly or implicitly sexist attack from a fellow candidate that pushed the Warren campaign into meltdown. It was a perceived abrogation of unity, in the form of a Sanders canvasser script that bent over backward to treat Warren with a deference that’s entirely unnecessary in a competitive primary election. Sanders’s supporters have every right to be aggrieved at Warren subsequently issuing the code red. (Meanwhile, the real beneficiary of this folderol, Joe Biden, grins to himself in a dark room, where he has been allowed to go and have a lie down.)

What makes this even trickier is the obvious glee with which the media, and especially CNN, is treating the spat. When CNN posted audio of the brief but much-analyzed post-debate confrontation between the candidates, in which Warren admonished Sanders for calling her a “liar,” a producer for The Lead With Jake Tapper tweeted, “This is clearly an escalation and a great story.” (The admission that this was the only interesting moment to come out of a debate that CNN hosted is par for the course for these self-awareness-deprived dunces.) It’s as if the media has been waiting all along for the two most left-wing candidates to really go at each other, and it is hard to tell whether that’s because it makes for such sizzling content or because they are thrilled to see the undermining of any threat to the status quo. The narrative that Bernie Sanders is sexist was set in stone in 2016, and there is nothing more fun than resurrecting the old story lines, sort of like the episodes of Frasier where Lilith came back. Sanders supporters are left in a bind. If they show anger, they court backlash—accusations that they are undermining the cause of beating Biden, or Trump, depending on which Democrats are incensed.

One might note that we’ve never yet emerged from a debate in which Biden’s disengaged and dismissive critiques of Sanders or Warren have been viewed as a “great story”—or earned him opprobrium for being divisive or harmful to the cause of party unity. There is a pervasive sense that the candidates who need to be admonished for their lack of unity are those on the left. Sanders is characterized as cranky and argumentative. Warren, when she has aimed her barbs at plutocratic cheats, has been criticized for doing things like using the word “fight.”

Meanwhile, Buttigieg and Biden earn plaudits with their calls to “bring people together.” In an earlier debate, Buttigieg responded to some fierce but not unwarranted criticism from Castro by declaring, “This reminds everybody of what they cannot stand about Washington, scoring points against each other, poking at each other.” Castro shot back, “Yeah, that’s called the Democratic primary election, Pete.” The Beltway touts called that round for Buttigieg. Castro went too far, by suggesting that there was a fight worth having, right then and there. Castro had taken his eyes off the real goal—defeating Donald Trump—sowing discord instead.

Must every substantive dispute between Democrats be treated as a distracting sideshow that inevitably leads to Donald Trump’s reelection? If the events of the past days can teach us anything useful, it’s that the Democratic field is filled with genuine rivals, who don’t necessarily think every one among them would be a good president. The actual underlying arguments that lead to many of their most heated confrontations are often worth interrogating. It’s a pity that cable news doesn’t care to do the work, opting to amplify superficial feuds instead. But for Democratic candidates to retreat in the face of conflict in the name of presenting some sort of unified front against Donald Trump serves only to deny voters the chance to really make informed choices about who should lead the country and who might better address their needs.

Eventually, there will be a unity candidate: the person who wins the nomination. Whoever that is will have the sole responsibility of unifying the Democratic base. Until that moment, everyone simply must calm down about the mythological threat of disaffected Democratic voters who, having been left too jaded by the primary process, cannot bring themselves to vote for a nominee who’s not their favorite. It’s true that in 2008, there were Hillary supporters who were upset at Barack Obama for winning; in 2016, there were people who voted for Bernie who went on to vote for Donald Trump, though most of those people were not really Democrats. But it’s impossible to say that these groups actually swung the election. Regardless, people are allowed to vote the way they want. The shrewder strategy is to assume that such voters are a permanent feature of our elections and make the necessary adjustments. (Here’s where one might consider that it could be worth reaching out to the disaffected Americans who currently don’t vote at all.)

In the meantime, we should let these candidates compete, debate, and criticize one another—recognizing that the ones who most often issue pompous paeans to “unity” are only doing so to duck the most necessary fights. And we should give voters of all stripes this time to argue for their principles, to like the candidate they’re passionate about and criticize the inadequacies of the ones they don’t. You should be allowed to support your candidate and loudly proclaim your belief that they’re better than any of the others. This happens to be what the candidates believe as well.