Growing up in North Carolina, I didn’t know anyone in a union. And it wasn’t until a few years ago, as I became involved in my own union as a journalist, that I learned my home state bans public-sector employees from collective bargaining. What started in part as an effort, in 1958, to break up cop and firefighter unions in Charlotte soon ossified into a state law covering all public employees. In 1981, the state also prohibited those same workers from going on strike. What that has meant in the decades since is that, even as the law has been challenged, workers must rely on the state’s increasingly conservative legislature when it comes to basic working conditions and salary standards. It’s a situation that some of these employees have called begging.

But over the past three years, teachers in North Carolina have bucked harder against the state Republican Party, which has been insistent on dragging what was once the progressive beacon of the South backward for going on a decade. Most recently, the issue of public-sector unionism was revisited last week, when the North Carolina Association of Educators conducted a survey of its membership in an effort to assess whether North Carolina teachers would be interested in going on strike regardless of the law. As The Coastland Times reported last week, “The NCAE is surveying teachers to find out how long they would participate in a work stoppage if the legislature doesn’t meet its demands, which include 5% pay raises, $15 minimum wages, Medicaid expansion and reinstating previous retiree health benefits.” (The co-chair of the NCAE caucus in charge of the survey told the Asheville Citizen Times that the average response was five days.)

It’s just a survey, but it’s more than that, too. This planning process arrives as part of a larger movement of American public teachers attempting to wrest back some sense of control of their jobs—over everything from salaries and class sizes to access to nurses and social workers for their students—at the bargaining table. From Los Angeles to Arizona to Denver, teachers in Right to Work states and more liberal states have been seizing the strength and leverage they have and trying to turn that into livable salaries and a career path that doesn’t leave you crowdfunding for school supplies or taking a second job.

A possible strike in North Carolina would be significant: The state currently has the second-lowest union membership rate in the nation, behind only South Carolina. In North Carolina and across the entire Bible Belt, uttering words like “union” or “strike” is often akin to taking the Lord’s name in vain, and Democrats and Republicans alike have worked to undercut organized labor. In one of the more egregious examples of this kind of bipartisan anti-unionism, Democratic Governor Roy Cooper signed a bill in 2017 that sought to cut the legs out from underneath a private union for seasonal farmworkers, who are among the most vulnerable workforce in a state that still derives a great deal of its economy from industrialized agriculture. The legislation outlawed the practice of employers removing union dues from farmworkers’ paychecks and prevented workers from requesting a unionization effort as the result of a legal dispute. It’s the standard playbook, a death by a thousand cuts model of weakening union efforts where the law is already stacked against workers.

There’s a long history behind this well-financed anti-labor sentiment and how it came to be so entrenched both in North Carolina’s laws and in its culture. The short version is this: The state’s economy was once largely constituted only of rural farming communities and factory towns, and the tobacco and textile executives worked hand in hand with the state to ensure unions could not sink their roots in the state. So even as North Carolina’s workforce has diversified, its government’s stance on labor hasn’t changed. Combine that with national efforts to demonize unions and paint them as the real enemy of workers, and you’ve got yourself a recipe for unchecked austerity for public workers and impunity among private employers. (Unsurprisingly, Republican lawmakers in North Carolina have been steadfast in their opposition to Medicaid expansion, despite majority support in the state and the fact that one million North Carolinians—or 10 percent of the population—lack health insurance because of our nation’s cruel and byzantine system.)

A budget duel between Governor Cooper and the Republican legislature has been brewing for months now, with barbs on who exactly is standing in the way of teacher pay and school funding being exchanged by both sides. If you listen to the talking points being offered by the likes of Republican state Senate leader Phil Berger, you’d be left with the impression that Republicans are wildly generous to teachers and responsible for “some of the largest pay increases that North Carolina’s teachers have seen.” This conveniently ignores the fact that those increases were only so significant because the Republicans absolutely shredded the public education system with a series of postrecession tax cuts that favored the wealthy. And these cuts didn’t just come for the teachers’ paychecks, but for the entire state’s school system: In 2017, North Carolina’s per-student funding rates were still 15.8 percent below the state’s 2008 levels when adjusted for inflation.

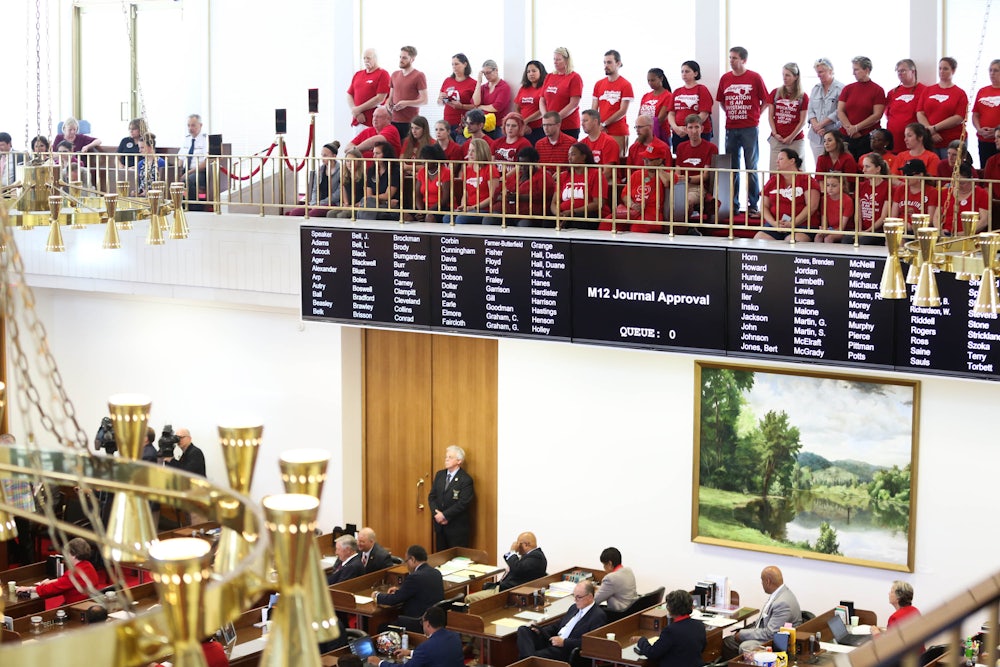

The underfunding of public schools—once the crown jewel of the state—has long been decried by teachers, though only recently have they begun to take mass action. In May 2018, roughly 20,000 teachers donned red shirts and marched on the state capitol in Raleigh, while Republican lawmakers called them “union thugs.” They repeated the march in 2019.

The organizing happening in North Carolina right now is in line with a national turn toward community-focused union militancy among teachers, but it carries risks: Participating teachers in North Carolina will be cast again as union thugs, when in fact all they’re doing is trying to stand up for themselves against a system designed to keep them quiet, poor, and working multiple jobs. It won’t be easy or pretty, and barring a sudden change in electoral makeup, it would set them opposite the law.

But there’s a model to win here: Teachers in West Virginia and Oklahoma both went against state law and walked out with overwhelming support from the public, forcing state legislators to hear and grant their demands. (In fact, West Virginia teachers did it twice, once over wages and funding levels in 2018 and again last year, when the state attempted to open the doors to charter schools.) These strikes were against the law, but the teachers, through their collective strength and with their communities, proved that these bills are little more than fear tactics when you’ve got the numbers on your side.