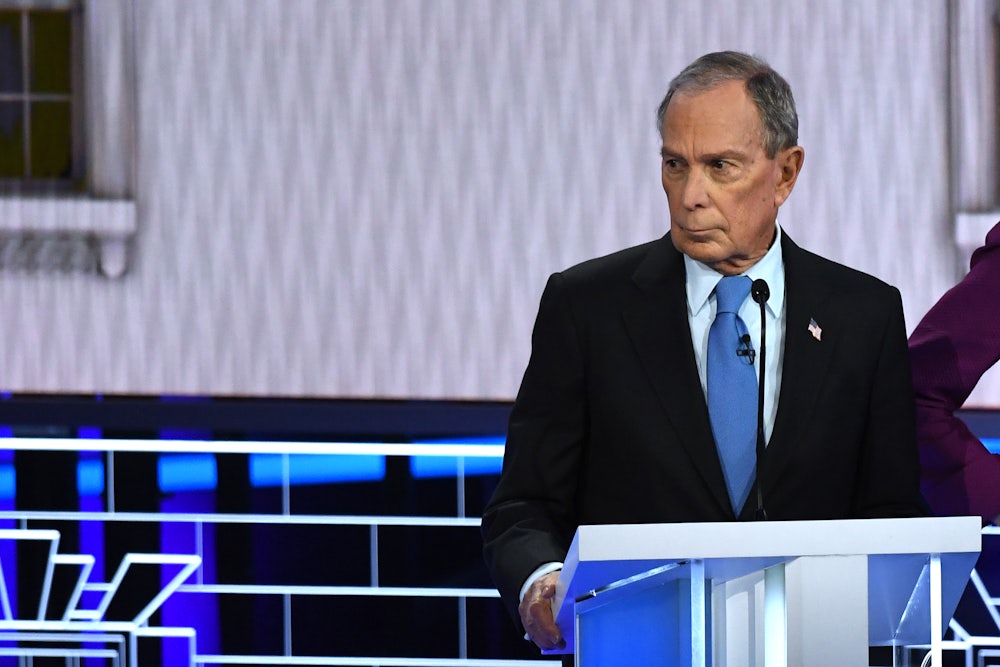

At Wednesday night’s Democratic debate, five of the candidates vying for the Democratic presidential nomination spent the evening taking pointed shots at one another. But all five reserved a particular ire for the wealthy former Republican who became the debate’s sixth participant after transmuting nearly half a billion dollars of his personal wealth into high poll numbers across the country, thus gaining access to the affair. Former New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg came under withering criticism for his history of sexist remarks and actions, his support of stop-and-frisk searches, and a number of other glaring weaknesses. To say that he struggled to defend himself would be an understatement.

After the debate ended, however, Bloomberg’s team kept its focus on the real enemy. “Tonight, Mike Bloomberg presented himself as the leading alternative to Bernie Sanders,” Bloomberg campaign manager Kevin Sheekey said in a statement. “Everyone came to get under Mike’s skin, but instead, Mike got under Bernie’s. Mike delivered the line of the night to Senator Sanders: ‘What a wonderful country we have. The best known socialist in the country happens to be a millionaire with three houses.’”

It’s been noted by many observers, myself included, that Trump is the sort of man that the Founders feared: a reckless demagogue with no interest in maintaining our democratic and constitutional order or the rule of law. Bloomberg, by comparison, may be the candidate that most of the Founders hoped would arise: a wealthy patrician, much like them, who would use his vast resources and influence to defeat what he views as disruptive elements in the nation’s political system.

Bloomberg’s campaign largely exists to suppress the two ascendant factions in American politics. One is the coalition of right-wing nationalists who currently hold power under President Donald Trump. Bloomberg’s core message does not extend far beyond the assertion that he is the best-positioned choice to win in November and restore some semblance of the antebellum system. “I am running to defeat Donald Trump,” he told a North Carolina audience last week. “I am running to restore honor to our government. We’re here to build a country we can be proud of and to get things done and do it in a united way, and that’s what we’re going to do. We’ve got to put ‘united’ back into [the] United States.”

His more immediate targets, however, are Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders and the Democrats’ ascendant socialist wing that hopes to obtain power—and tax his wealth. Until this fall, most centrists had hoped that former Vice President Joe Biden would keep Sanders at bay. But after Biden’s numbers collapsed and his claim to electability faded, Bloomberg rushed to pick up the mantle. A deluge of ads cast him as the heir to Obama’s progressive legacy, as well as a bare-knuckle New Yorker with the resources and pugnaciousness to beat Trump at his own game. What went largely unspoken was his hope that he could keep the party from veering any further leftward.

Bloomberg’s campaign got this far because his message resonated with a substantial number of likely Democratic primary voters who desperately want Trump removed from office. His candidacy is also built upon structural flaws in the nation’s political system. A recurring trope in American politics is that the best person to fix what’s wrong with Washington would be someone so wealthy that they can’t be bribed or bought by special interests. Trump exploited this folk belief to ruthless effect during the 2016 election, casting himself as an anti-corruption warrior for a bipartisan swamp. He then went on to decisively disprove that idea as president.

Some of these structural flaws were intentional. In the Federalist Papers, James Madison warned that a purer democracy would be unable to tame what he described as the “mischiefs of faction.” Such democracies, he wrote, “have ever been spectacles of turbulence and contention; have ever been found incompatible with personal security or the rights of property; and have in general been as short in their lives as they have been violent in their deaths.” He instead favored a more republican system, where power would be wielded by a representative class “whose wisdom may best discern the true interest of their country, and whose patriotism and love of justice will be least likely to sacrifice it to temporary or partial considerations.”

Those beliefs influenced the creation of undemocratic institutions like the Electoral College, which exists to overturn the popular will, and the Senate, which exists to dilute it. It would also take generations of reformers and a bloody civil war to incorporate more than just landowning white men into the American polity. More recent generations have added setbacks of their own. Thanks to Buckley v. Valeo and an array of similar Supreme Court rulings that followed it, the modern campaign-finance system feels indistinguishable from systematized bribery, increasing the allure of wealthy individuals who can operate beyond its grasp.

In a healthy political system, Wednesday’s debate performance would have marked the abrupt end of Michael Bloomberg’s presidential aspirations. Instead, it’s possible that political realities will be overwhelmed by his ability to flood the zone with an endless supply of favorable depictions of himself. As a result, he may yet maintain his current strength in the polls ahead of Super Tuesday, at which time a substantial portion of Democratic delegates will be awarded. This raises some damning questions for the Democratic Party and its supporters, as my colleague Osita Nwanevu pointed out earlier this week. It also underscores the need for deeper structural reforms to American democracy itself.