On Wednesday, the Supreme Court will hear oral arguments in its first major abortion case in four years. The case, June Medical Services v. Russo, is not a direct challenge to Roe v. Wade or Planned Parenthood v. Casey. That gives the justices no opportunity to overturn the two Supreme Court decisions that established the modern legal framework for abortion rights in America. But the good news for abortion-rights proponents likely ends there.

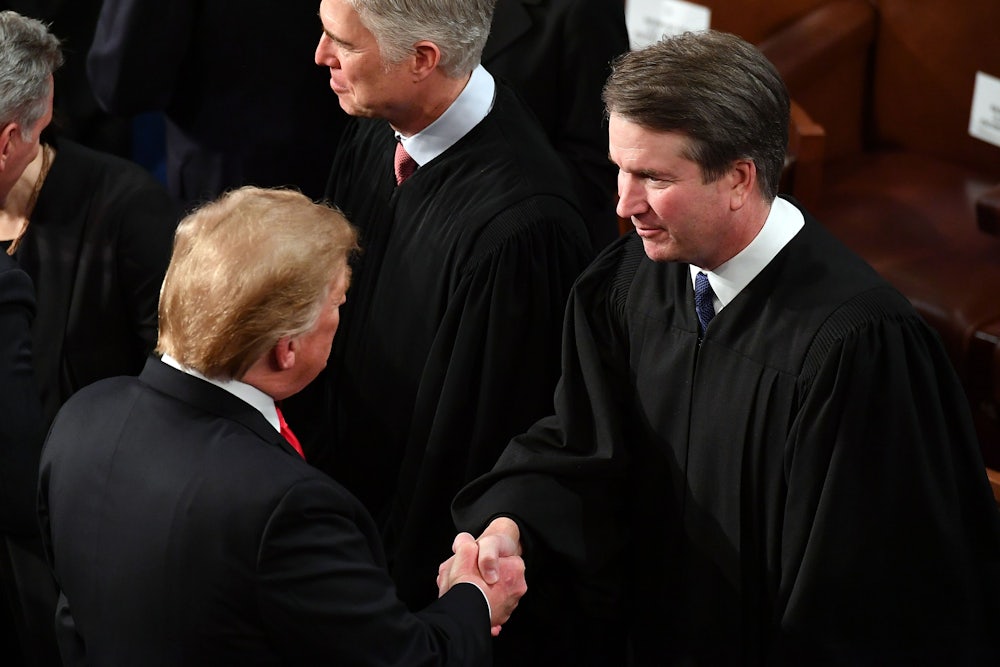

It’s possible that the justices may block the state law in question from going into effect, leaving the status quo intact. But the 2018 confirmation of Justice Brett Kavanaugh to succeed the retiring Anthony Kennedy, who had provided a sort of judicial firewall to abortion rights, makes such an outcome unlikely. Instead, the court’s conservative majority will likely take one of two possible approaches, either of which could unleash a wave of new restrictions on abortion access for half of the country. The only question is which path the justices will take.

The most straightforward option would be to uphold Act 620, a Louisiana law passed in 2014 that’s at the center of the case. Act 620 is what’s known as a TRAP law, which stands for “Targeted Regulation of Abortion Providers.” Such laws use ostensibly neutral changes in state health and safety laws or building codes to force abortion providers out of business. Act 620, for example, requires that doctors who perform abortions have admitting privileges at a hospital within 30 miles. A federal district court in Louisiana blocked the law from going into effect after determining that it would force multiple clinics to close. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit overturned that ruling and upheld the law in 2018.

This is hardly uncharted terrain. The Supreme Court struck down a similar law in Texas in Whole Woman’s Health v. Hellerstedt just four years ago. In addition to a nearly identical admitting-privileges requirement, the Texas law also required abortion clinics to meet the same regulatory standards required of surgical ambulatory centers. In a 5–4 decision, the court’s liberal justices and Kennedy found that the restrictions amounted to an “undue burden” for Texas women who sought abortions. “Targeted Regulation of Abortion Providers laws ... cannot survive judicial inspection,” Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg wrote in a concurring opinion.

In Louisiana’s telling, however, the Hellerstedt ruling was far more narrow than Ginsburg had suggested. The state argued that the Texas law only reached the Supreme Court after it went through a laborious fact-finding process in the lower courts. “This Court in Hellerstedt determined, after a searching factual review in an as-applied challenge, that the Texas admitting-privileges statute was unconstitutional,” Louisiana told the justices in its brief for the court. “[June Medical Center] would use that conclusion to facially invalidate all other similar statutes, regardless of facts specific to those providers or to the jurisdiction at issue—eliminating the factual inquiry the Hellerstedt Court found essential.”

June Medical Center noted that the district court had done extensive fact-finding of its own before rendering its decision. “In sum, each legal argument the State and the Solicitor General make about Act 620’s benefits and burdens was made and rejected in [Hellerstedt], and each factual argument was made and rejected by the district court based on extensive record evidence,” the providers argued in their reply brief. “If the rule of law is to be honored, the Fifth Circuit’s decision must be reversed.”

The greater problem, the providers argued, was that the Fifth Circuit had replaced the lower court’s factual conclusions with its own in order to effect an end-run around Hellerstedt. “A properly functioning legal system depends on certain basic operating principles,” the providers told the court in their own brief. “One is the maxim that legal holdings of higher courts are binding on lower courts. Another is that a trial court’s factual findings govern on appeal unless clearly erroneous.” If those rules are set aside, they warned, “the public and political branches may cease respecting the courts as true guardians of the rule of law.”

The other threat is a potential shift in how the courts determine who can fight abortion-related regulations in court. In the 1976 case Singleton v. Wulff, the Supreme Court ruled that a doctor who performed the procedure had the legal standing to challenge a state Medicaid provision on abortion. Generally speaking, litigants can only sue on their own behalf, and not for others. But the court held that women who seek abortions may not be able to pursue litigation for financial or privacy reasons, and that the doctor-patient relationship was close enough to justify the exception.

Louisiana disagrees. In its brief for the court, the state argued that there are no practical barriers for women who want to challenge abortion laws today. “If ‘Mary Doe,’ the pregnant plaintiff in Roe’s companion case, could challenge a statute requiring abortions be performed in a hospital, there is no reason to presume that women are hindered from challenging an admitting-privileges requirement,” Louisiana told the court. “Abortion patients today continue to challenge abortion regulations in their own names or through legal guardians.” The state also questioned whether June Medical Center and its doctors had a close relationship with their patients, pointing to past citations against the clinics as evidence that their interests may diverge.

At least one justice has shown a willingness to accept this argument. In his dissent from Hellerstedt in 2016, Justice Clarence Thomas wrote that “the very existence of this suit is a jurisprudential oddity.” He accused past and present colleagues of carving out exceptions in abortion cases to suit their whims. In his eyes, the third-party doctrine was simply another anomaly. “This suit is possible only because the Court has allowed abortion clinics and physicians to invoke a putative constitutional right that does not belong to them—a woman’s right to abortion,” he wrote. No other justices joined his dissent, however.

The providers responded with a host of critiques to the state’s position. They told the court that Louisiana hadn’t raised the standing question until after the providers asked the Supreme Court to review the Fifth Circuit’s decision, effectively forfeiting the opportunity to raise it now. What’s more, the state had affirmatively told lower courts that it did not question the providers’ standing to challenge Act 620. And if that wasn’t enough, the providers claim they have the personal standing to challenge the law regardless. “Hope and its physicians are directly injured by Act 620’s admitting-privileges requirement and its very real threat of criminal sanctions,” they told the court.

Questions of legal standing may seem abstract and procedural. But they can have a decisive effect on who participates in the legal process. This case, like most that involve abortion, drew a large number of friend-of-the-court briefs from third parties who have an interest in the outcome. One of the most striking briefs came from a group of women lawyers who had obtained abortions. They outlined the stakes in practical terms. “[Louisiana would require that a patient-plaintiff initiate legal proceedings—with all that entails, including finding and retaining a lawyer and potentially engaging in invasive civil discovery—nearly contemporaneously with making the decision to terminate, and simultaneously with trying to access medical care,” they told the court.

If the justices rule that abortion providers can’t challenge restrictions on behalf of patients, those patients would then be forced to file lawsuits themselves—a grueling option that would likely be out of reach for minors, lower-income women, and others without the necessary resources to pursue it. “As an attorney, I know firsthand what litigation entails—invasive document discovery, depositions and cross-examinations, a person’s entire private life laid out before a court,” one of the women lawyers said in a quote in the group’s brief. “Women seeking abortions go through more than enough.”

If, on the other hand, the court opts to set aside the standing question and uphold Act 620 directly, the practical effects would be immediately felt. Should Louisiana’s law go into effect, all but one of the state’s abortion clinics would close, the providers told the court. And by accepting the Fifth Circuit’s narrow interpretation of Hellerstedt, the justices would be inviting other lower courts, particularly those with large contingents of Trump appointees, to uphold similar restrictions in other states. Roe and Casey would remain intact for now. But for women who live in Republican-led states where the procedure is already difficult to obtain, it would be exceedingly hard to tell.