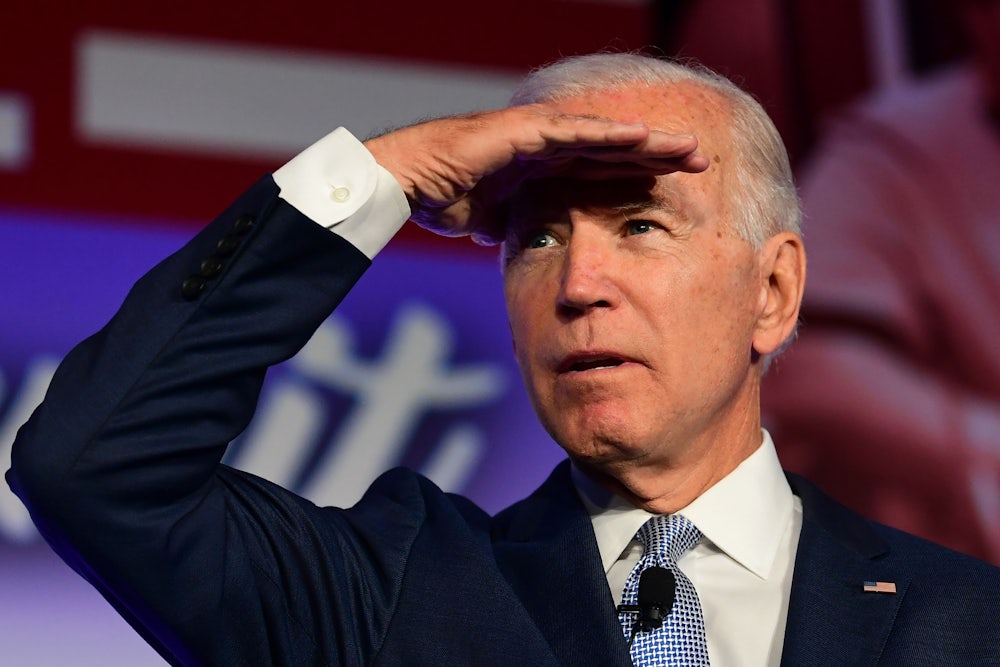

Once one of the weakest Democratic presidential hopefuls on climate, presumptive nominee Joe Biden won activists’ praise when his campaign announced it was bringing Bernie Sanders–aligned progressive leaders, including Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and the Sunrise Movement’s Varshini Prakash, to a joint climate task force in mid-May. It’s one of several recent overtures toward the party’s younger and more left-leaning wing. The question, particularly for climate voters hoping for more ambitious climate policy than Barack Obama’s, is how meaningful these gestures really are: whether they truly signal an aged moderate’s attempt to get serious about global warming.

Climate voters have good reason to be wary. In 2016, much of the energy from Bernie Sanders’s primary campaign was funneled into the DNC Platform Committee, a body of some symbolic importance but whose relationship to actual party policy priorities can vary. This time, however, some progressives are more optimistic about their ability to influence the next Democratic administration. “There are enough people with genuinely progressive impulses on these,” said David Segal, executive director of Demand Progress, referring to the climate task force and other such bodies, “that, if they turn out to be total bunk, there’s a good chance that would be signaled.” The big difference between now and 2016, Jeff Hauser, executive director of the watchdog Revolving Door Project, told me, is that “Bernie-aligned groups this time are focusing on appointments much more and the platform less.” That is: Progressives in 2020 are interested in “getting people in the room where personnel decisions are being made.”

Julian Brave NoiseCat, vice president of policy and strategy for the think tank Data for Progress, has been in touch with Biden’s campaign since Super Tuesday about climate issues and is one of many progressives compiling a list of names for staffing a new executive branch. “What if we had folks whose family had been on welfare informing this country’s economic policy? What if we had people who come from communities that were impacted by hurricanes in the last 20 years who were shaping this country’s approach to climate change? That’s kind of the way in which a new generation of progressives could shake up the swamp,” he told me. “We want to figure out how far we can go.” (Disclosure: I am a senior fellow at Data for Progress. I have had no role in its work communicating with politicians.)

A candidate’s transition team, tasked after the election with filling the roughly 4,000 political appointments throughout the executive branch, has tremendous impact on an administration’s trajectory and can say much more about a candidate’s priorities than their official platform or their party’s official platform does. As a financial reform advocate, former Delaware Senator Ted Kaufman’s reported role in Biden’s transition effort has encouraged some progressives. In addition to the formal, federally funded transition process, a more ad hoc one occurs within the incoming president’s inner circle to determine top Cabinet posts, from attorney general to the Treasury. “You want as many people in this process as possible,” said Hauser.

Progressives are also concerned about keeping those likely to block climate progress out of Biden’s “kitchen” and official Cabinets. For example, the Sunrise Movement and Justice Democrats have called for Biden to drop Larry Summers as an adviser. As the incoming and then acting head of Barack Obama’s National Economy Council, Summers made key decisions to shrink the size of the planned stimulus package and eliminate greener and more ambitious proposals. Michelle Chan, of Friends of the Earth Action, which is generating its own list of potential White House staffers across agencies, also singled out Blackrock CEO Larry Fink—whom Biden donors have floated as a potential Treasury secretary pick—as someone whose name should be taken off any short list. Lower-level officials deserve scrutiny, too; in the primary, climate groups criticized Biden’s campaign for bringing on Heather Zichal as an adviser on climate and energy issues. Zichal, once on the Domestic Policy Council in the Obama administration, served on the board of natural gas company Cheniere Energy from 2014 to 2018. Calling out some appointees’ and advisers’ fossil fuel ties, activists argue, can influence the wider scope of who gets offered jobs moving forward.

While climate issues have traditionally been confined to agencies like the Environmental Protection Agency, or departments of Energy and the Interior, plenty of other posts hold power over reducing or fueling emissions. In an economic system centered on fossil fuels, few policy fields won’t be involved at some level in decarbonization. The Department of Agriculture will need to plan how to maintain food production through droughts and higher temperatures, as well as tackle the methane-producing and pathogen-developing world of industrial meat production. Mid-level Treasury appointees liaise with the State Department in crafting trade policies that govern how the United States imports and exports emissions, and can set the agenda for international institutions like the World Bank and International Monetary Fund. The General Services Administration—which handles government procurement—can decide whether America’s massive federal vehicle fleets and buildings run on clean energy. In some cases, bodies that would appear to be mostly irrelevant to climate can exercise a deciding vote over decisions made in others. The head of the National Credit Union Administration, for instance, has a voice on the Financial Stability and Oversight Committee, which could play an instrumental role in assessing the risks posed by fossil fuel companies and how to handle the coal, oil, and gas assets those companies abandon as they become too costly or risky to dig up out of the ground. “Basically the entire executive branch is going to matter on climate work, especially if you’re in a situation in which the Senate is either majority-controlled by Mitch McConnell or hinges on a swing vote from Joe Manchin. Realistically speaking, you’re going to need a high-energy executive branch,” said Hauser. “A whole of government approach is going to be really important, and very few executive branch appointments are unrelated to a green agenda.”

Evergreen Action, formed out of Washington Governor Jay Inslee’s climate-focused primary run, has been in talks with the Biden campaign on policy. “What we really need is a full mobilization of the federal government,” said Maggie Thomas, Evergreen’s political director. Per its expansive plan, that would involve two crucial steps: every single federal agency accounting for its role in the climate crisis and a larger restructuring of the federal government to take that on. The group knows that will require a lot of people. “We wish there was a ZipRecruiter to fully staff a government that could take on climate change,” Thomas joked. Evergreen staff and affiliates Sam Ricketts, Bracken Henricks, and Rhiana Gunn-Wright recently outlined their plan for a White House Office of Climate Mobilization, modeled on the cross-agency bodies that led the transformation of the domestic economy during World War II.

Critically, certain agencies—the Office of Management and Budget and the National Economic Council, in particular—exercise de facto veto power within interagency processes. “You could have the best EPA administrator in the world,” says Hauser. “If they get overruled by OMB or NEC, it’s kind of irrelevant how good they are, or how hard they fight.” They’ll need to be not just comfortable with the idea of decarbonization but proactively committed to making it happen. The flip side of these agencies’ outsize power, Hauser added, is that an NEC head who’s enthusiastic about a green agenda could enforce that across Cabinet posts. That the NEC is generally staffed by economists could be a problem, considering the discipline’s historically limited thinking on climate. “One of the highest areas of importance to get climate action baked into an administration is to make sure that as many of the economic policy positions as possible are staffed by economists who understand climate and give a fuck about it,” Brave NoiseCat told me. “And I think that’s going to be really hard.”

There are other bodies to consider, as well. Courts filled with right-wing judges may well sink promising climate measures that come out of the White House, as they did the Clean Power Plan. And the Federal Reserve, an independent central bank governed through White House appointees, holds enormous leverage over whether the U.S. treats climate change as a systemic risk—which it has so far declined to do. “They can’t pick one solar company and just give them money,” said Alexis Goldstein, senior policy analyst at Americans for Financial Reform, “but they could absolutely say that continued investments in fossil fuels are a risk to the stability of the financial system.” Asked about the most critical posts from a climate perspective, Evergreen’s Jamal Raad listed OMB director and Treasury secretary as his top picks, along with the Federal Reserve chair and U.S. trade representative.

Avoiding climate catastrophe will mean undoing not just the damage caused by deregulation by the Trump administration but also decades of bipartisan attacks on the administrative capacity of executive agencies, which could be the biggest drivers of decarbonization. These attacks have been paired with a disparaging and devaluing of government work, leading talented personnel to pursue careers in the private sector on the wrongheaded assumption that exciting and innovative things can’t happen if Uncle Sam is paying the bills. Filling thousands of posts with talented candidates serious about tackling today’s crises—whether in 2021 or beyond—requires making government jobs something to be proud of, where people can try, fail, and experiment.

In some ways, the combination of Joe Biden’s relatively thin climate credentials and fairly disorganized, lightly staffed primary campaign could represent an opening for climate advocates. “There’s no secret Google document that, if you accessed it, would tell you what the Biden administration would look like in 2021,” Hauser says. “There’s definitely the possibility to take Biden’s rhetoric about a Rooseveltian presidency and make it a reality. It’s all subject to influence, for better and for worse. The various bad guys—Blackrock, Goldman Sachs, or fossil fuel companies—are all scheming. It’s not like progressives are the only people paying attention. But in the past, the corporate interests were thinking very deeply about these hidden jobs. Now progressives are fighting for them, too.”