A few days after Thanksgiving, as the number of coronavirus cases surged to alarming new levels in Los Angeles, Mayor Eric Garcetti tweeted out an advisory that, on its face, should have been fairly innocuous: Limit non-essential activities, wear a mask, and keep physical distance. But after months of missteps surrounding a raging pandemic and a police force that turned peaceful events into violent showdowns, Garcetti’s tweet had become—like so much of his messaging—unintentionally incendiary. It didn’t help that, just hours earlier, a local homeless outreach organization discovered the city had approved a filming permit that resulted in the cancellation of hundreds of Covid-19 testing appointments at one of the city’s few transit-accessible locations. (The appointments were reinstated the following day, a decision fueled in part by national backlash to the news that a TikTok star-fronted reboot of She’s All That had left more than 500 people without access to Covid-19 testing.)

“God you’re a useless trash suck up,” Jamie Patterson, a local barista, replied to Garcetti after asking him whether he’d been given a speaking role in the movie. (The mayor’s roster of film and TV cameos is not insignificant: He’s credited on IMDB for playing such close-to-home roles as “Wildly Unpopular Mayor” and “Guy Who Will Never Ascend Above Local Politics.”) Other replies, like the one from the indie rock band Best Coast, went with a more classic sentiment: “God I hate you so much.”

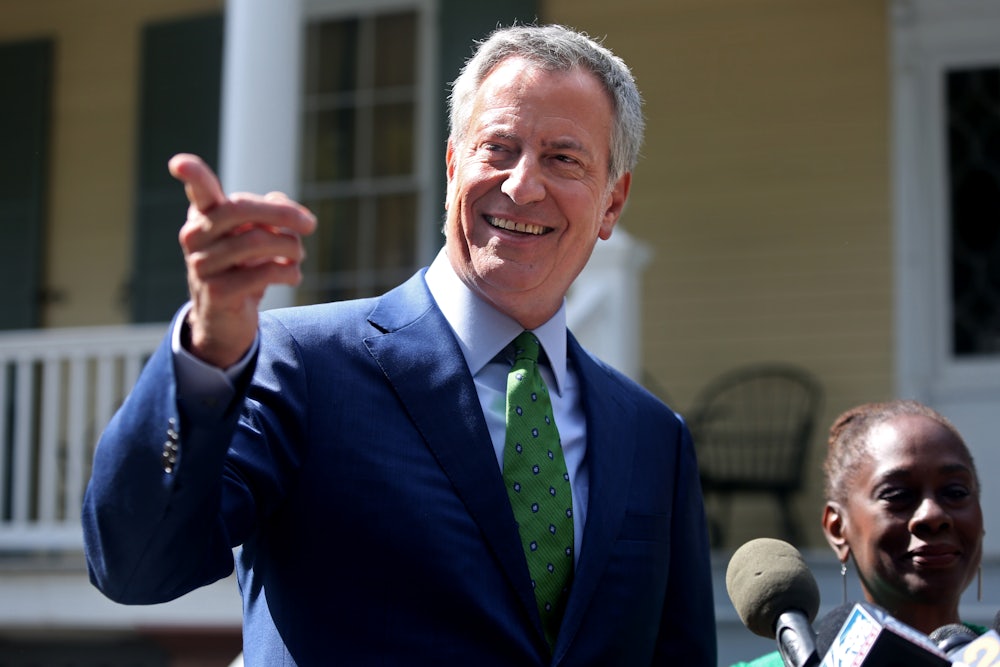

The specifics of Garcetti’s biography make him a particularly ripe target, but the phenomenon of tweeting mean things at your mayor isn’t unique to Los Angeles. In New York, Mayor Bill de Blasio’s puzzlingly slow, insufficient response to Covid-19 all but certainly cost some people their livelihoods and others their lives. When de Blasio defended the police after officers drove a car through a crowd of protesters last summer, it only inflamed the anger and frustration, spurring sit-ins in front of his home and headlines such as “Everybody Hates Bill” and “Bill de Blasio Has Failed.” The disgust at their respective mayors has inspired camaraderie—and a series of Twitter memes—not just among Angelenos and New Yorkers but also those who have marched to their mayors’ homes or initiated recall efforts in Cleveland, Seattle, D.C., Portland, St. Louis, and Chicago. Through a mess of overlapping crises this year, it seemed small moments of joy, or at least something like catharsis, could be found in the simple act of bullying your mayor.

As even the most well-funded, Democratically controlled cities have completely fumbled their responses to both the Covid-19 pandemic and a lethal epidemic of police violence, mayors have become signifiers of our country’s sweeping failures at the most basic levels of government. The pervasiveness of anti-mayoral bullying, particularly among those who may not have previously paid attention to their local elected officials, has spawned memes and t-shirts that read, “Not now sweetie, mommy’s cyberbullying the mayor.” As the pandemic recession stretches on, unemployment remains high, food lines in many cities are long, and a federal eviction moratorium is soon to expire. When so much of day-to-day life has been canceled or thrown into turmoil this year, why not tweet obscenities at your mayor—as a little treat?

More than that, bullying the mayor has also become part of a larger organizing strategy—and evidence of a widespread political awakening. Groups like Ktown for All, which first reported the cancellation of Covid-19 testing appointments, have gotten people fired up about otherwise obscure civic issues by tweeting irreverent pop culture references and challenges at the mayor. When their initial tweet about the film shoot went viral, racking up more than 1,000 retweets, they quipped: “Damn this blew up. Peep our Soundcloud,” linking to a Google doc containing comprehensive information on protests, petitions, and social media actions including dozens of templates for anti-Garcetti tweets, gifs to include, and hashtags such as #HesNotAllThat.

But bullying the mayor also just feels good. “There is something really satisfying about telling Garcetti to eat shit on Twitter,” Patterson, a prolific replier to Garcetti tweets, told me.

The president and Congress can feel far off and unaccountable, largely by design, when it comes to our daily lives. Mayors, as the highest-ranking public officials in towns and cities, are often the literal face of local power. In many larger cities, the mayor is elected separately from the City Council—whose members represent individual areas of the city—and has veto power over their legislation. While the scope of their power differs depending either on that city’s charter or state law, it’s the mayor who often serves as the city’s spokesperson, delivering speeches and press conferences and taking the heat for a range of potential disasters they may or may not have personally created. Nevertheless, plenty of people have discovered this year that their local elected leaders have hardly proved more capable than those in the White House. (City government programs in Los Angeles including a lottery for rental assistance and the reinstatement of parking tickets with a reduced fee have been roundly ridiculed as insufficient and even insulting.)

With high unemployment and cities under lockdown orders, “People have more time to commit to looking at their local government and what’s going on and recognizing why we’re in such a failed state,” said Brigid McNally, an activist who showed up to recent protests at Garcetti’s house. McNally remembers discovering Twitter as a forum for ranting to the mayor—and occasionally seeing results—back when Garcetti first got elected, in 2013. Her then-boyfriend had tweeted at the mayor about a pothole, she said, and it got filled the same day. “I was like, ‘Oh, maybe this is an effective way of communicating with the mayor.’”

But potholes are just one part of it. Like Ktown for All, groups including Black Lives Matter and People’s City Council have used their platforms to draw attention to the inner workings—and often, the failures—of local government. Both groups regularly live tweet City Council and police commission meetings (which are now streamed online as a result of the pandemic), provide context around policy proposals, and organize in-person actions including the recent sit-ins at Garcetti’s house.

“People’s City Council formed out of the frustration that you had a city council and you had a city in lockdown facing extraordinary circumstances and a total breakdown—everything shut down—and it left a lot of people high and dry,” Trinidad Ruiz, an organizer with People’s City Council, told me. “The half-measures that they would put forward to pretend like there were solutions really began to anger people. Nobody was working, everybody was at home, and you’re watching this farce play out and these elected leaders just going through the motions.”

While the coalition takes aim at a number of elected officials, including the city councilmember it helped oust last November, it specializes in unabashedly trolling the mayor, with memes that incorporate pop culture and local landmarks. “Fuck Garcetti” has become a popular chant at protests, and the group has turned it into a slogan on t-shirts and stickers. The url fuckgarcetti.com links to a list of stats that are anything but flattering.

In Minneapolis, it was the city councilmembers, not the mayor, who heeded the calls of activists and pledged to dismantle the city’s police force in the wake of George Floyd’s murder. While that pledge has since turned into a much more modest diversion of funds, Mayor Jacob Frey has done little to repair community relations with police—or trust in city government. When he told a crowd of protesters that marched to his house last summer that he didn’t support the abolition of the city’s police department, he was met with shouts of “Shame! Shame!” and “Go home Jacob!” The critique has continued online, where his recent tweet about receiving an award from the local Urban League was met with a steady stream of reaction gifs expressing an utter disconnect from reality. “Jacob have you considered actually talking to your constituents?” one asked.

In Portland, another solidly blue city, residents actually have something in common with President Trump: an affinity for dunking on Mayor Ted Wheeler—albeit for very different reasons. In late August, following months of protests, Trump admonished the mayor on Twitter, calling him a “fool” for not bringing in the National Guard to tame them. But Trump had in fact already called in federal agents who, just a month earlier, ended up tear gassing Wheeler himself during his attempt to make peace between police and protesters. The tactic didn’t work; protesters chanted “Fuck Ted Wheeler” and called for him to resign after failing to remove federal officers from the city. Unsurprisingly, the replies to his tweets—the tone and content of which are nearly interchangeable with Garcetti’s or Frey’s—are filled with memes and gifs that respond to his seemingly empty government rhetoric.

The collective rage directed this year at the likes of Garcetti and his New York counterpart, de Blasio, stemmed at least in part from their aspirations to ascend the very office to which voters elected them. In 2017, the year he was reelected, Garcetti spent nearly a third of his time traveling outside of California, The Los Angeles Times reported; his frequent trips to swing states boosted speculation that he was planning to run for president in 2020. He ultimately scrapped the idea of running, but the damage had already been done. By that point, community activists had begun circulating mock “missing” signs to draw attention to the time Garcetti had spent away from his office amid a ballooning homelessness and housing crisis.

Mayor de Blasio, meanwhile, announced his run for president in May 2019, ignoring a poll that showed 76 percent of his own constituents thought he shouldn’t run. (Never mind that even the most likeable sitting mayors have never been elected president.) He suspended his campaign just four months later, on the heels of a Vox explainer titled “Why Bill de Blasio is so hated.” After de Blasio’s exit from the presidential race, his predecessor, Michael Bloomberg, decided to try his hand. The former New York City mayor ended his three-month campaign in March but not before spending $900 million of his own money on it.

The end of Garcetti’s most recent ambitions came, at least for now, at the hands of another hated (former) mayor: Pete Buttigieg. After Buttigieg was announced as Biden’s transportation secretary on Tuesday, ruling out the possibility of Garcetti’s appointment, activists in Los Angeles claimed victory and declared an end to more than three weeks of daily protests in front of Garcetti’s house.

The decision, of course, means Garcetti will remain in office a while longer; his term ends in 2022. But it also means there will be no shortage of opportunities to tweet “eat shit” or to put him on blast for the next misstep, right alongside so many others who are just as angry, in cities all across the country. Because at a time of overwhelming despair, there is at least a small comfort in knowing that nearly everyone hates their mayor.