“They must be the most contented people in the world.” This is how the 1980 comedy The Gods Must Be Crazy introduces the San peoples of the Kalahari Desert, better known as the Bushmen. They eke out a simple living, the narrator explains, digging for roots and tubers, hunting with bows and arrows, and collecting dewdrops from leaves. “For the most part they live in complete isolation, quite unaware that there are other people,” the narrator continues. Thus they remain until a pilot drops a Coke bottle from his plane, and a hunter named Xi finds it. The shiny object quickly roils his otherwise happy community, so Xi sets out to hurl the “evil thing” off the end of the world.

The South African movie broke box-office records, including the U.S. record for the highest-grossing foreign film, and spawned four sequels. Much of its success stemmed from the winning performance by the San actor N!Xau, in the role of Xi. The film’s director and writer, Jamie Uys, played up N!Xau’s image as a naïf, telling The New York Times that, before Uys found him, N!Xau had only ever seen one white man. Plucked from the bush, he was baffled by the ways of the wide world, Uys said: He didn’t understand what “work” meant, and the sight of a toilet amused him. Even after the film turned N!Xau into an international star, Uys had to keep the bulk of N!Xau’s pay in a trust fund, he explained, as N!Xau couldn’t “handle big sums yet.”

Or so he said. N!Xau, when anthropologists interviewed him later in life, told a different story. He’d grown up on a farm, not in the bush. He understood money perfectly well; he’d worked as a cook at a local school and had been making a bow and arrow set to sell to tourists when he first met Uys. On the topic of money, N!Xau expressed annoyance that Uys was “living in luxury” after their first film’s success while N!Xau was still “living in a hut.” And Uys’s portrait of the San as living in placid isolation? “The image of the Bushmen given by the Gods films is not really good,” N!Xau felt, “because it does not show how people are really living.” Indeed, by the 1980s, foraging was a thing of the past, and most of the San were living impoverished lives in resettlement areas. N!Xau expressed surprise that audiences mistook the film for reality and didn’t get that he was “just acting.”

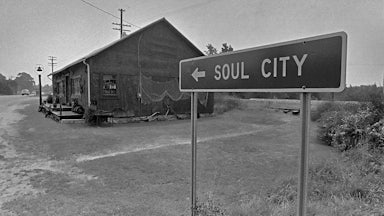

Still, The Gods Must Be Crazy, more than any other movie or book, has cemented the image of the San in the public eye. This has been enormously frustrating to anthropologists, who tend to regard Uys’s portrayal of the San as both condescending and misleading, in that it conceals the wretched treatment of Kalahari populations by Southern African governments. The San’s prime chronicler, Richard Lee, deemed it a “thinly disguised piece of South African propaganda.” The idea that “some San in the 1980s remain untouched by ‘civilization,’” Lee added, was “a cruel joke.”

Yet there is one anthropologist who has grudging respect for the film. In the eyes of the South African anthropologist James Suzman, The Gods Must Be Crazy carries a “subversive message,” one worth contemplating. The San, who in the middle of the twentieth century were “one of the last of the world’s few largely isolated hunting and gathering societies,” represent one of our closest links to the world before agriculture, Suzman writes. What we know of their foraging lifestyle suggests that they were, if not the “most contented people in the world,” then at least surprisingly well-off, heirs to an easy abundance that characterized most of Homo sapiens’ history. The San, Suzman writes, “by rarely having to work more than 15 hours per week had plenty of time and energy to devote to leisure.” In offering a glimpse into their disappearing world, The Gods Must Be Crazy makes a withering critique of our present-day, toil-obsessed labor regime.

Suzman’s first book, Affluence Without Abundance, was a study of the economic lives of the Ju/’hoansi (known also as the !Kung), a group of San people. Elaborating on its ideas, Suzman has now written a second book, Work, a global history of labor from the Stone Age to the present. He’s not the first to propose that prehistoric peoples offer important lessons for postindustrial societies. Through caveman diets, the advice of psychologist Jordan Peterson, and bestselling histories by Jared Diamond and Yuval Noah Harari (one of Suzman’s blurbers), the Paleolithic has become oddly relevant. Suzman’s book shows the appeal, but it also shows the difficulty of making plausible claims about the distant past—and why social criticism grounded in prehistory so often falls short.

Among anthropologists, James Suzman is a renegade. Almost two decades ago, he bucked norms in the discipline by attacking the relevance to Africa of indigenous rights. This put him at odds with the human rights group Survival International’s campaign to protect San claims to land in the Kalahari Desert, where diamonds had been discovered. Suzman felt that Survival International was using political concepts unsuited to Africa to scuttle a vital compromise between Botswana’s government and the San. Survival International implied that Suzman was just shilling for the diamond company De Beers, for which he’d worked as a consultant.

The accusation was a serious one, especially given the great wariness with which most anthropologists regard any corporate work, to say nothing of working for the diamond industry. Suzman, however, seemed unfazed; diamond mining was “the lifeblood of the Botswana economy,” he wrote. He later took a full-time job at De Beers, serving from 2007 to 2013 as its global director of public affairs. “He wants to be there, at the top table, where the money is,” Survival International director Stephen Corry told me. But Suzman saw it differently. Working alongside the suits, he explained to The Guardian, taught him to empathize with them.

Yet corporate life, however empathy-eliciting, didn’t satisfy him. “I began to dislike myself terribly, sitting there thinking: ‘How’s my bonus going to look this year?’” he explained. And so he veered back toward anthropology as the CEO of Anthropos, a consulting firm that offers “thought leadership” to organizations seeking “a competitive edge.” Its clients include Sony Pictures, National Geographic, the European Commission, and—this was probably inevitable—De Beers. Its website shows a poster from The Gods Must Be Crazy and asks what we might learn from “traditional hunter gatherer economies.”

That question is an old one. In 1966, the anthropologists Richard Lee and Irven DeVore, both of whom also researched the Ju/’hoansi San, convened a now-legendary conference at the University of Chicago, called “Man the Hunter.” It was an occasion to revise core assumptions about hunter-gatherers, particularly the notion that theirs was a miserable lot. Lee had carefully observed Ju/’hoansi communities in Botswana—among the last people still foraging—and calculated that on average they spent only “from twelve to nineteen hours a week” getting food. It seemed that, despite inhabiting a harsh environment and possessing only rudimentary tools, they were living far easier lives than their air-conditioned, supermarket-shopping contemporaries.

This was an astonishing finding, all the more so if, as Lee softly suggested, the Ju/’hoansi could be taken as a stand-in for foraging societies in general. Did all humanity once live so effortlessly? Time magazine reviewed the published proceedings of the “Man the Hunter” conference (those were the days) and rhapsodized about the “elysian community” of the Ju/’hoansi, “in which the work week seldom exceeds 19 hours.” It quoted the anthropologist Marshall Sahlins, who’d attended the conference, remarking that the Kalahari’s foragers represented “the original affluent society.”

Lee’s findings were important but controversial. By the 1980s, prominent revisionists challenged Lee, particularly questioning the notion that the San had maintained their way of life intact since prehistoric times. Rather than standing aside from history, Lee’s critics argued, the San had been manhandled by it, forced onto undesirable lands as an underclass. The “Kalahari debate,” as it was known, grew heated and bitter, and it was particularly damaging to Lee’s way of thinking. Today, very few cultural anthropologists would treat present-day communities, no matter how “traditional” they may seem, as windows on to distant eras.

Very few, but not none. James Suzman detects an “extraordinary level of cultural continuity” between the twentieth-century foragers of the Kalahari and those from more than 100,000 years ago. He has described visiting the Ju/’hoansi as like being “stranded in a Paleolithic world,” which is putting it more starkly than Lee himself ever did. Suzman has little patience for the Kalahari debate; he feels it “distracted the anthropological community from the most important and interesting aspect” of Lee’s finding, on the nature of work. If foragers can get by with a 15-hour workweek, shouldn’t that tell us something? Especially as the gig economy, automation, and the pandemic have thrown our working world into crisis? Our addiction to economic growth is currently killing us via climate change. Perhaps we ought to aim to live simpler and less rushed lives. Original affluence, Suzman feels, is “an idea whose time has come yet again.”

It’s not just foragers’ working hours that Suzman feels deserve renewed attention, it’s also their way of thinking. The Ju/’hoansi and other groups that were still foraging in the twentieth century appeared surprisingly uninterested in socking away surpluses. Instead, they trusted in “the providence of their environment.” This allowed them to take only what they needed, when they needed it. Such “economic confidence,” wrote Marshall Sahlins, had them “laughing through periods that would try even a Jesuit’s soul.”

This happy-go-lucky attitude, Suzman notes, was enabled by a sharp ethos of sharing. Those with food were obliged to share with those lacking, not as beneficence but more as a tax. Suzman is especially taken by the Ju/’hoansi practice of “insulting the hunter’s meat.” When someone returned with a large kill to share, the norm was not to praise his generosity but to deride him. This, Suzman notes, was a way to “tear down any potential hierarchies before they formed.” It was a society based not on admiring the rich but on mocking them.

The past tense is necessary here, because Suzman, who started working among the Ju/’hoansi in the 1990s, only glimpsed this world in the rearview mirror. With the exception of a few isolated, small groups, true foraging societies are today extinct. Suzman mourns how rural Southern Africans have crowded into slums, where they’ve endured unemployment and crime. People once content to share what little they had are today tormented by flagrant inequalities and spurred ceaselessly onward by what sociologist Émile Durkheim called the “malady of infinite aspiration.” The Neolithic revolution, which replaced foragers with farmers starting some 12,000 years ago and implanted our current economic sensibility, now covers the earth.

There’s a certain poetry to the surge of interest in Paleolithic lifeways, coming just at the moment of the near-total extirpation of foraging societies. But there’s also something puzzling about it. Why should an audience of cell phone wielders be fascinated by peoples whose most sophisticated tools were made of wood and stone?

Suzman gives a clue. In his telling, the prehistoric and the postindustrial have much in common. Suzman’s description of foraging communities makes them sound an awful lot like Silicon Valley start-ups, at least as those firms understand themselves. Suzman’s prehistoric groups are scrappy and adaptable, with little regard for formal institutions or material objects. They have an egalitarian culture based on sharing—one thinks of the culture of collaboration and free distribution that launched so many IPOs—but they retain a fierce individualism. Arrow poison and digging sticks are their “killer apps,” as he puts it. They are minimalists who trust that the world will provide for them. And it does.

The appetite for prehistory is strong in Silicon Valley, where tech CEOs fawn over Yuval Noah Harari. Harari is another defender of the “original affluence” thesis, and it sometimes feels as if Suzman, whose Work reads like a duller version of Harari’s Sapiens, is fishing for Harari’s fan base. Work also shares an odor with internet entrepreneur Timothy Ferriss’s The 4-Hour Workweek, which invites readers to “join the new rich” by reconceiving their relationship to work. Understanding ancient foragers’ work hours, Suzman writes in his conclusion, can “loosen the claw-like grasp that scarcity economics has held over our working lives,” freeing us to “imagine a whole range of new, more sustainable, possible futures.”

This is the appeal of deep history. Contemplating the Paleolithic shows us the span of our species and helps us appreciate social configurations that have not been dominant for thousands of years. It is precisely the sort of outside-the-box sensibility that today’s entrepreneurs laud. So, where does it lead?

In theory, looking at history through Suzman’s wide-angle lens can generate insights of any sort. Yet in practice, time scales have a way of encouraging certain conclusions and discouraging others. The sharpest social critics have generally focused on recent centuries, where they have located the roots of capitalism, empire, racism, extractivism, and technocracy. Pulling the camera all the way back to the scale of the species is better suited for broad reflections about human nature, often concerning health. Harari’s Sapiens is more a plea for veganism and mindfulness than for any particular social order. “Harari’s big idea boils down to this: Meditate,” Bill Gates has appreciatively written. When asked by The New York Times why he’s so popular with the Silicon Valley elite, Harari hypothesized: “One possibility is that my message is not threatening to them.”

Also unthreatening is the work of Jared Diamond, who is with Harari our prime interpreter of the prehistoric. He, too, subscribes to the “original affluence” thesis. Diamond’s prescriptions are of the same therapeutic character as Harari’s. In his 2012 book about “what we can learn from traditional societies,” The World Until Yesterday, he has suggested eating less salt, learning more languages, and letting children roam. “There aren’t many other writers who go as broad and as deep as he does,” writes Bill Gates, Diamond’s relentless champion.

Not all books about prehistory are so resolutely apolitical. The anthropologist James C. Scott’s incisive Against the Grain is another self-described “deep history” that sympathizes with ancient foragers. Yet for Scott, the problem with the agricultural revolution is not just what it did to our diets but what it did to our societies by enclosing them within coercive, hierarchical states. Asking about the Paleolithic becomes a way to break free of the habits of deference that modern life engenders. Scott’s deep history feeds into his career-long defense of anarchist practices, rooted in his appreciation for the “state-evading peoples” of upland Southeast Asia. One might expect a similarly sharp political edge from Suzman’s Work, given the author’s extensive experience watching the Ju/’hoansi and other Southern Africans tormented by their governments and global market forces.

But one would be disappointed. Work, for all its promised insights of long-term thinking, ends with surprisingly tepid conclusions. Suzman criticizes ballooning executive pay and pointless jobs, yet these appear in Work less as targets for activism than as symptoms of our mixed-up modern world. This is a book about work that treats slavery and the gendered division of labor as minor topics and says virtually nothing about unions. The structuring elements of our work lives appear in his 300,000-year panorama only as small smudges at the edge of the canvas. We often criticize those who take narrow views for missing the forest for the trees, but there’s such a thing as taking too broad a view and missing the forest for the solar system. From Suzman’s galactic perspective, there’s disappointingly little to say about labor. His takeaway is just that prehistoric people “had few material desires,” which “could be satisfied with a few hours of effort”—so maybe we all could stand to work a little less.

Much hangs, in the end, on that prehistoric 15-hour workweek. Yet for all the research that’s been done, we still understand very little about Paleolithic societies. There’s an ax—or, we call it an ax—that humans made all over the planet for more than a million years, and we’re, ah, not totally sure what it’s for. Is it an awkward tool? A prop in a courtship display? Currency? It’s hard to say. You can see why, faced with filling out time sheets for workers who lived more than 100,000 years ago, writers like Suzman are tempted to use modern foragers as stand-ins. And that brings us to a second peril of the lessons-from-the-Stone Age genre: how hard the deep past is to know. In both of Suzman’s books, a great deal rests on Richard Lee’s Ju/’hoansi study from the 1960s, which is the sole authority Suzman cites for his vaunted 15-hour figure. Is he on solid ground?

No.

There’s really no other way to say it. James Suzman’s marquee fact, upon which the edifice of his 300,000-year history precariously balances, is astonishingly squishy. Seeing how he got there shows how much caution is required in writing of the distant past. Caution, unfortunately, is not one of Suzman’s strengths.

Let’s start with Richard Lee, who wrote in 1968 that the Ju/’hoansi spent “from twelve to nineteen hours a week” getting food. I presume he used a range to highlight his research’s imprecision, but if we require a single figure, we could use the midpoint: 15.5 hours. This was at the low end of ethnographic observations at the time; Marshall Sahlins’s overview of forager studies estimated an average of 21 to 35 hours a week for the food quest—and that was before Lee’s critics had weighed in. Yet Suzman, who is nothing if not bold, clings to Lee’s study and writes that foragers like the Ju/’hoansi “rarely worked more than fifteen hours a week” and “spent the bulk of their time at rest and leisure.” Already, he has a toe over the line (if the midpoint of Lee’s range is 15.5 hours, how could foragers’ hours have “rarely” exceeded 15?), but not far enough to land him in author jail.

Except that’s just the start. As criticism emerged, Lee revisited his math. Recalculating, he offered a slightly higher average: “about 20 hours.” Lee further conceded that “it would be misleading” to use that figure on its own, as it counted only hours spent procuring food (the same is true of Sahlins’s figures). Of course, foragers must do other things to make their living as well: craft tools, butcher meat, grind nuts, draw water. Adding such tasks to the food quest, Lee concluded that Ju/’hoansi foragers had a 42.3-hour workweek, which is longer than the current 35-hour U.S. weekly average for most paid work.

Even Lee’s revised accounting omitted tasks that other anthropologists categorized as work. In what must be one of the most painfully on-the-nose episodes in the history of anthropology, Lee’s wife, Nancy Howell, published her own study of the Ju/’hoansi, noting that Lee had declined to count childcare as a form of labor. The original affluence thesis, Howell continues, contains an “element of truth” but ultimately “misrepresents the reality” of lived experience. The Ju/’hoansi she knew in the 1960s (and she was right there, alongside Lee) might not have been visibly busy every waking hour, but this could be explained by their being overheated and exhausted. Howell’s medical research describes the Ju/’hoansi as thin, short, and not very fertile—all worrisome signs of scarcity. She notes that even if their practices of sharing averted outright starvation, they still experienced “gnawing hunger,” and malnutrition was probably “a contributing cause” to deaths from disease. By her calculations, the Ju/’hoansi lived on average 30 years.

Suzman cites Lee’s later writing and makes one brief mention of non-food-quest hours (he is silent about Howell’s research), but somehow this does not shake his faith in the Ju/’hoansi’s laid-back lives. Undaunted, and in defiance of much ethnographic evidence, he extrapolates wildly into the deep past. “The fifteen-hour working week was probably the norm for most of the estimated two-hundred-thousand-year history of biologically modern Homo sapiens,” he has written. Lee’s contested and subsequently revised four-week study of one camp in the Kalahari in the 1960s becomes, in Suzman’s garbled rendition, the history of our species.

Perhaps it’s the difficulty of writing history at the scale of the species that has left the field open for corner-cutters like Suzman. If so, that’s a pity. We could use good histories of Homo sapiens—reliable ones that culminate in something more than diet tips or life hacks. A 300,000-year history of work, done well, could ask probing questions about gender, slavery, inequality, the wage system, ideology, and workers’ political power. It might yield conclusions that would be more uncomfortable than encouraging to our ascendant elite. It might, indeed, offer insights as to how to dismantle that elite.

But Suzman’s Work is not that book. It uses the distant past—in its fun-house mirror way—to highlight some pathologies of our age, yet without giving much understanding of how to cure them. As Suzman doesn’t recommend returning to foraging and hasn’t pointed to any levers with which to change things, his book ends with a weak injunction to think creatively. Here, blue-sky thinking collapses into something near fatalism. Maybe there’s nothing to be done. Sometimes the gods are just crazy.