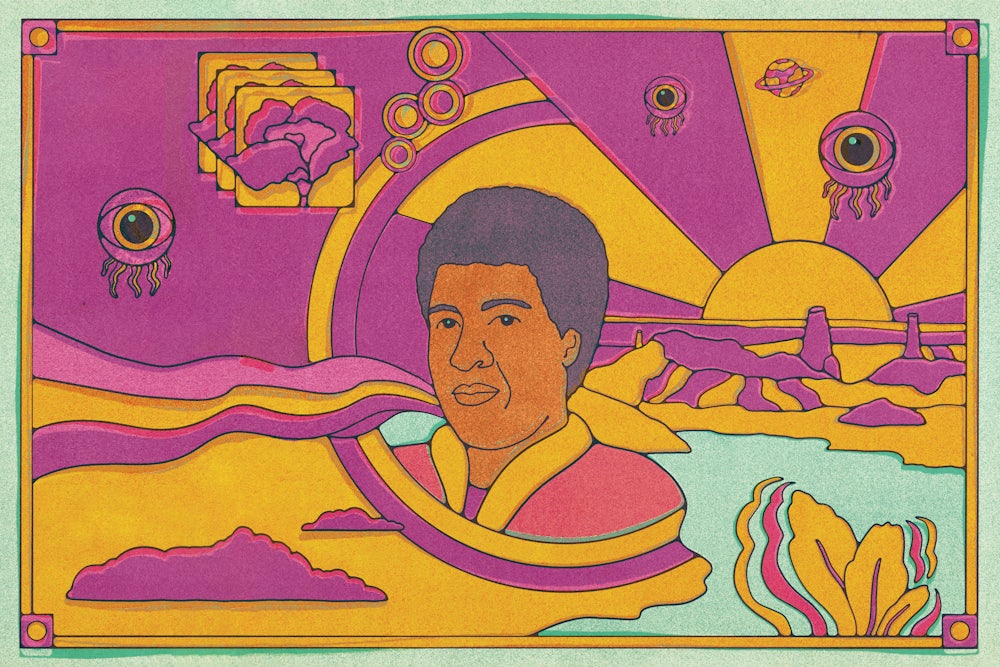

Parable of the Talents, Octavia Butler’s penultimate novel, follows a charismatic Black woman named Lauren Olamina as she struggles to defend her commune, escapes a prison camp, and builds a religion, intending to send her followers to outer space. Published in 1998, the novel takes place in the 2020s and 2030s, when climate change has plunged the American West Coast into a rolling refugee crisis, the rule of law is sporadic at best, and voters have selected a demagogue devoted to “making America great again.” It’s a bleak future, and Lauren’s brother, Marcus, understandably rejects her goals: “All he wanted to do, he said, was to earn enough money to house, feed, and clothe his family. Once he was able to do that, he said, then maybe he’d have time for science fiction.”

The novel appeared three years after Butler won a MacArthur Foundation “genius” fellowship, the first science-fiction writer to receive that honor. She knew what it meant to struggle, though unlike Marcus she knew why some of us need science fiction, not just as a way to envision another world but a way to understand how we got this one. Raised with few resources in Pasadena by a mother who cleaned houses, Butler heard early on (so she recalled in a brief memoir) that “Negroes can’t be writers.” Feeling “ugly and stupid, clumsy and socially hopeless” throughout childhood, she kept on writing stories, and while still in her teens she conceived of the plot that became her Patternist series of novels. After an associate’s degree at Pasadena City College, Butler took writing workshops at UCLA and found her way in 1970 to Clarion, the nationally renowned science-fiction workshop, then held in Pennsylvania. There the famously cantankerous Harlan Ellison encouraged her, accepting a story for his infamous anthology The Last Dangerous Visions, which—as the SF world well knows—never appeared.

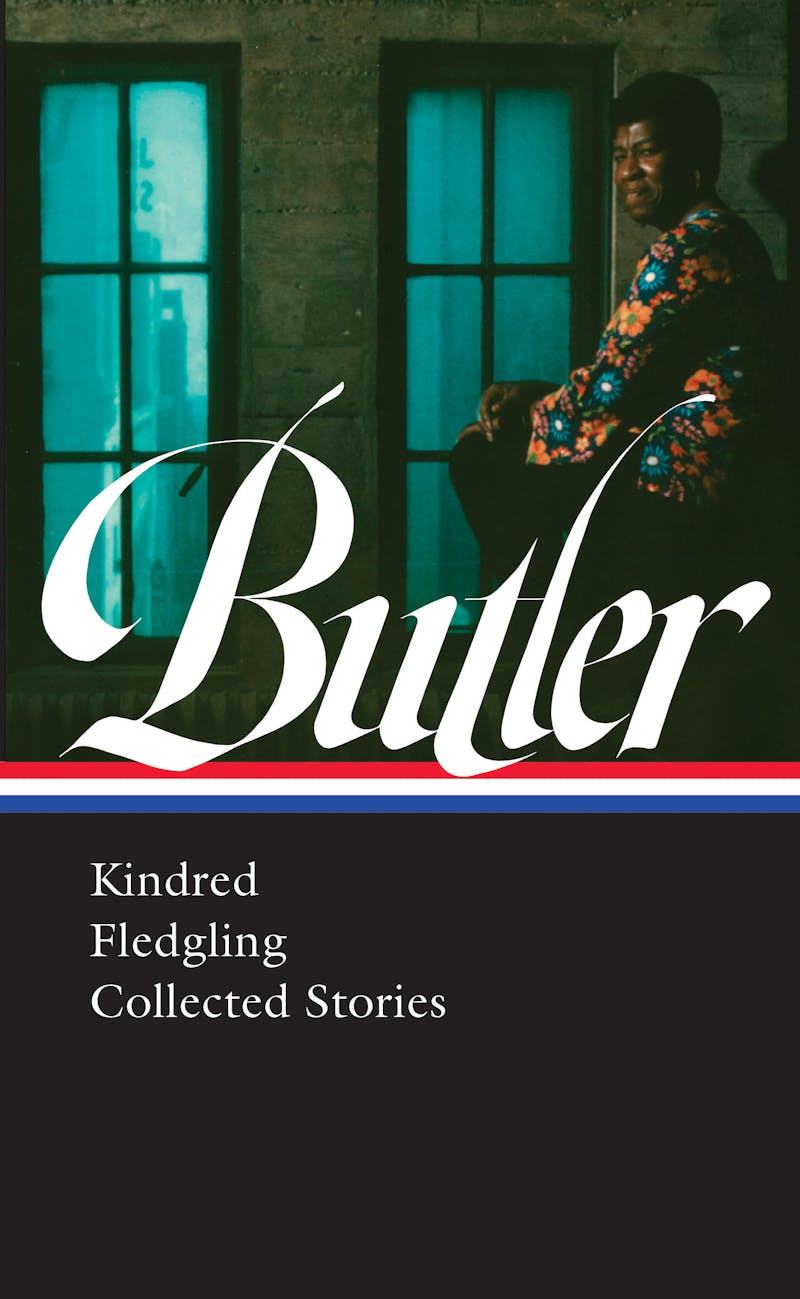

Butler had, she recalled, “five more years of rejection slips and horrible little jobs” ahead of her before she “sold another word.” The 1976 novel Patternmaster inaugurated her career. Based first in Los Angeles and then in Seattle, she would publish 12 novels and several short stories, up to her sudden death after a fall in 2006. For decades she seems to have been the only Black woman who made a living through science fiction, though writers such as N.K. Jemisin and Nnedi Okorafor now stand among its leading practitioners. Despite SF’s then-overwhelming whiteness, Butler won five Hugo, Nebula, and Locus awards (the highest in the field). Yet even in her last years—as the scholar Gerry Canavan has shown—Butler could not live without self-doubt: Her false starts, discarded drafts, and obsessive revisions may outnumber completed works.

You can love those works even if you do not read much SF. (Indeed, you can teach them. Many do.) Butler’s prose is always a windowpane, never a jewel trove; she’s a writer who deals out novelties carefully, if at all. Critics and celebrators have stressed the accuracy of her predictions, her place in Black American letters, and her knack for disillusion. Her stories of epic or everyday mistreatment, captivity, cruelty, and even torture instantiate what she called, in her Xenogenesis trilogy (1987–89), the “Human Contradiction,” the “genetically inevitable Human conflict: intelligence versus hierarchical behavior.”

If we are to stay afloat, she implies, we must change. “God is Change,” says one of the many slogans in Olamina’s cultic verse. Taken as a whole, Butler’s work admits how thoroughly we have been shaped by our biology and by our history, by sexual desire, by habit, by plenty or by scarcity, by xenophobia and by anti-Blackness. Our drive for power over one another may doom us all. And yet Butler’s later works suggest how human beings might not only adapt to change but initiate it: how we might give up our toxic demands for power over one another—and over ourselves. This Butler belongs not just to traditions of African American literature and to traditions of rigorous science fiction (even her vampires have biological bases), but also to traditions of queer culture-making, as she questions every social and especially every sexual arrangement, imagining ways of life that she did not live to see.

Butler’s best-known novel remains Kindred (1979), a perfectly constructed time-travel story. The wary, practical protagonist, Dana, gets repeatedly and mysteriously transported from her modern Los Angeles home into antebellum Maryland, sometimes with, sometimes without her white husband, Kevin. She shows up whenever her white ancestor, the impulsive future slave owner Rufus, fears for his life: She returns to the present when and only when she herself might otherwise die. Dana has to save Rufus’s life over and over so that her ancestors can get born. She sees and hears—that is, Butler describes—a near-fatal whipping, the forced separation of families, and the sale of young children. By the end of the novel, Rufus has “sent me to the field, had me beaten, made me spend nearly eight months sleeping on the floor of his mother’s room, sold people … He’s done plenty, but the worst of it was to other people.” (Dana means, specifically, that she was not raped.)

A Black woman sucked back into the slaveholding past, Dana loses “much of the comfort and security I had not valued until it was gone.” Within the rough plot of Kindred hides a gentler, partly untellable story about what the child Rufus could have become. “I would have all I could do to look after myself,” Dana says. “But I would help him as best I could … maybe plant a few ideas in his mind.” But the ideas wither. Her journeys through time create a closed loop, producing the present from which she departs, and to which—emotionally scarred, and literally maimed—she returns.

Americans, Butler’s plot implies, can review our abused and abusive past, but we cannot undo it. “To survive,” Dana muses, “my ancestors had to put up with more than I ever could.” We benefit from our ancestors’ sacrifice. If we also benefit from white supremacy, from the shape of American capital, we might be no better than Rufus and his family, who profit from cruelty at a remove. “It was part of the overseer’s job to be hated and feared while the master kept his hands clean.”

Butler’s events echo those described in real enslaved people’s writings, especially Frederick Douglass’s 1845 Narrative, also set in Maryland. But Kindred also ends up in conversation with earlier stories about time travel, such as Mark Twain’s A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court (1889). In both novels, an American goes back to the past, tries to make it better, and sees how stubbornly privilege maintains itself, how hard it must be to direct any change.

“I began writing about power,” Butler once said, “because I had so little.” Hannah Arendt’s distinction between power and violence—the first a tacit cooperation or compact, the second mere force—makes no sense in the world of Kindred, nor in most of Butler’s worlds: Consent, political, legal, or sexual, is at best contingent and suspect, at worst nonsensical. We did not, could not, consent to our own existence beforehand: We are born into the country that we get—for 330 million of us, the United States—not a country we chose in advance. It is a country founded on anti-Blackness, on white supremacy, on what that very un-American thinker Michel Foucault called biopower, the use of knowledge and law and information not to create free or equal individuals but as a channel for force.

Butler thinks about biopower often: All bodies are potentially outside the law, and all information a means of control. Slaveholders try to prevent Black people from organizing themselves by learning to read: Telepathic Patternists learn to control one another and themselves by reading minds. And minds require bodies. Rufus’s callous father finds Dana astonishing in her mysteriousness and in her modern pride: “You come out of nowhere and go back into nowhere,” he says. “You’re not natural!” But the most important facts lie elsewhere: “you can feel pain—and you can die.”

It is the distinctive role of science fiction to expand our perceptions, to help us articulate—however guardedly, or ironically, or wildly—ways of life we might not have imagined before. The worst thing you could say about Kindred—and about the Patternist series, with its grim allegories and its realistic pandemic—is that these books almost never let us do that: They only, as Kevin says, “try to understand.”

But then Kindred is barely science fiction. Fledgling, and the short stories, as well as the Xenogenesis series, certainly are. The only novel Butler could finish in her last eight years, Fledgling begins with a point-of-view character reduced—like so many people elsewhere in Butler—to bare life, “nothing in my world but hunger and pain.” Having survived a fire, the vampire Shori wakes up amnesiac, disoriented, alone, and starving: She kills a man without knowing what she’s done. Then she lets herself get picked up, and sheltered, and taken to bed, by a construction worker named Wright, whom she also—pleasurably—bites. She looks “way too young,” prepubertal, “super jailbait,” though really she’s in her fifties (vampires age slowly). She realizes that she’s the product of biotech: “I don’t know who the experimenters are,” “the ones who made me black.” Nor does she know who tried to burn her to death. She looks like another of Butler’s survivors.

And then she learns that she can do more than survive. Vampires—who call themselves Ina—have a culture, and Shori must learn it. Her dark skin comes from her spliced human genes, which also allow her to move about in daylight. Ina clans devoted to racial purity see her as an abomination, but her own clans will try to protect her. She and Wright and her other lovers and allies navigate a relatively simple thriller plot, fleeing Washington state for coastal California one step ahead of the bad guys.

Butler’s vampires—not magic demons, but “long-lived blood drinkers”—“live alongside, yet apart from, human beings, except for those humans who become our symbionts,” creating polyamorous two-species pods. These pods enjoy “mutualistic symbiosis”: Their humans live longer and healthier than other humans, and “choose to mate with one another,” as well as with their Ina protectors, who in turn mate and bear Ina children according to elaborate inter-clan rules. Ina saliva harbors “a powerful hypnotic drug.” One bite, and a human gets pleasure. More than a few, and the human’s addicted; they neither can, nor wish to, live apart, and they must obey vampires’ direct commands.

Read Fledgling in a bad mood and you might see the humans as manipulated prey, Shori’s Ina allies as predators no better than the rest. You may even see another of Butler’s allegories of slavery, since her vampires cannot survive without multiple human dependents: Those who bite only one or two people eventually kill them and need more. Read Fledgling again and you might see, instead, uniquely powerful and uniquely vulnerable figures trying as hard as they can to create consent, and chosen family, and earned loyalty, amid unpropitious conditions. Though she’s a vampire who must feed to live, Shori tells a new partner, before addiction sets in, “I think it would be wrong for me to keep you with me against your will.”

All vampire families are extended families; all involve erotic bonds. Shori explains to Wright what would happen if she fed only on him: “That would kill you. Quickly.” She must instead shape “a household” with “five or six others. We don’t all have to live in the same house … but we need to be near one another.” Whether gay, straight, or something else, human symbionts must sooner or later accept same-sex members of their family; they may well share beds. Supposedly heterosexual men, in particular, find this task hard. It’s one of many problems Shori must solve in order to keep her new family safe. (Real-life polyamorous humans call the analogous problem the One-Penis Policy.)

Other problems require physical self-defense. Good Ina elders respect their human symbionts; they make “good teachers,” too. Bad ones treat humans as “tools,” and will stop at very little to erase Shori, the human-Ina hybrid, from the earth. The bad clans perpetrate more arson, more murders, as our heroes flee. Determined to “do what’s necessary to sustain” them, Shori leads her people through violent confrontations and into a fraught public trial with vampire judges. She says of her humans, “I’ll do all I can to keep them safe.” In return, she “must show” Ina clans “that you can follow our ways.”

Shori’s adventures, in between debates and gunfights, can read like polyamory memoirs. The vampire elder Preston gives Shori advice that might have come from The Ethical Slut. Of her lovers, he says, “Each must find a way to accept the other’s relationships with you. You must help them do this.” As Wright and another human symbiont sleep in a car, Shori reflects, “I wanted to crawl between them again.… They were both mine. And yet there was something deeply right about seeing them together as they were.” Fledgling could read quite differently—and less agreeably—were Shori less vulnerable (for a vampire), or white, or a man: As it is, we see all the ways in which she represents the disempowered, even as we also learn how much power she has, and we stay with her as she negotiates the closest thing in Butler to enthusiastic consent.

Butler sometimes dismissed Shori’s story as minor: “Fledgling was me having fun.” It is fun. It’s also continuous with other, older work. The Ina amount to a present-day, easier-to-process version of the tentacled Oankali from the Xenogenesis trilogy, space aliens who rescue—or “rescue”—humanity after a global war, ensuring humans a future of sorts by mating with us in five-partner units. Each unit includes one ooloi, a third sex with healing powers. Butler’s ooloi narrator in Imago (1989) wonders, “What would happen to me when I had two or more mates?... Would I have to be hateful to one partner in order to please the other?” (Since they’re part Oankali, the answer is: of course not.) Like Ina, the Oankali generate “deep biological attachment.… Literal physical addiction to another person.” Like Ina, they may live a very long time, and they wish to reorganize, and improve, the life cycles of their human companions, at the cost of human independence.

If you want weird hope along with your hard dose of history, the trilogy, along with Fledgling, may be the best place to start. (The Xenogenesis series remains in print as one paperback volume under the title Lilith’s Brood.) It’s ingenious, like Fledgling but more so. And yet it can feel, today, like an author pushing very hard at a half-open door. Writing before the widespread availability of tentacle porn in the United States, Butler expected her Oankali to repulse humans; writing before the widespread visibility of people who prefer they/them, she assigned the pronoun “it” to her ooloi. She wrote as if it would be hard for everyone (and impossible for some) to accept these new, nonmonogamous kinds of families. (“Resisters” who insist on living apart from the aliens, and on bearing wholly human children, can immigrate to Mars.)

But some people are already into tentacles; some people are already bi- or pansexual. Some people seek out novelty, “built to dream outwards,” as the great and troubled SF writer James Tiptree Jr.—one precursor to Butler—put it. Some have chosen families they could not have imagined when they were young, with multiple partners or with none. And some—in fact, many—are into vampires. Fledgling could—should—be Butler’s gateway drug.

If the MacArthur award brought Butler broad attention, her prominence within SF began earlier, neither with tentacles nor with telepaths: The first awards she won all went to short stories. Her stories round out the Library of America’s volume; they also fill out Butler’s career-long explorations of biopower, survival, force, and consent. In “Speech Sounds,” a pandemic that takes away literacy, speech, and language itself has created a Hobbesian Los Angeles “where the only likely common language was body language,” where “law and order were nothing—not even words.” Even here, children need “teachers and protectors” among the rare humans who can still communicate. As usual in Butler, raising the young is the only unproblematic good.

In “Bloodchild,” intelligent alien arthropods called Tlic lay eggs that hatch into grubs inside human hosts. In the story’s key exchange, its human male narrator tells a looming Tlic, “I don’t want to be a host animal.… Not even yours.” The Tlic responds that he will be no such thing: Rather than treating humans as pets, or as “property,” modern Tlic “wait long years for you and teach you and join our families to yours.” Critics understandably saw Tlic-human relations as a version of slavery: Instead, Butler insisted, “Bloodchild is my pregnant man story,” “a man becoming pregnant as an act of love.” (The difference between human men and human women, throughout her oeuvre, seems more rigid than it might today, when men get pregnant all the time.)

As for her last significant short work, “Amnesty” (2003), it too inspires contradictory readings, about subjugation and survival, or about submission and consent. In it, enormous plantlike spheres called Communities have taken control of the planet. The spheres recruit human beings to live within them, a totally alien but (for some) pleasurable environment, and we must realize that we cannot defeat them, whether or not we choose to join them. Butler’s protagonist, Noah, (the name is a giveaway) tries to bring the gospel of new, strange, protective erotic communities to a mostly resentful human herd. “You try to help your own people to see new possibilities and understand changes that have already happened,” Noah muses, “but most of them won’t listen and they hate you.”

Butler consistently revised her drafts—so Gerry Canavan shows in his monograph on her—to make them more hopeful, less gruesome, or less grim. She yearned to complete what her journals call a YES-book, not the NO-books she kept generating instead: “Love your readers. Say yes!” she wrote on one note to herself. It’s no wonder those readers—Canavan included—keep on seeing Butler’s giant NO: no to whitewashing, no to Whig history, no to any insistence that consent and choice and self-fashioning are always possible, no to the notion that good must prevail. No, above all, to the idea that we can ever become independent, autonomous masters of ourselves or of other people: If there is ever to be a next generation, we need one another, flawed as we are.

Characters in Butler’s fiction who insist on proud independence end up dead, or wishing they were dead. Characters who seek and accept some kind of community—however compromised, however sexualized—may, with luck, find alternatives to biopower, to the dominance hierarchy by which human beings are either owners or owned. The Oankali don’t think human beings can make it: We’re “bright enough to learn to live on your new world,” one says, “but you’re so hierarchical you’ll destroy yourselves trying to dominate it and each other.” In Parable of the Talents, Lauren Olamina disagrees: There may be “solid biological reasons why we are the way we are,” as well as reasons deep in history—and yet we can still “make something more of ourselves.”